|

Remote route-finding on Earth's largest landslide to a huge panorama of southern Utah.

Related

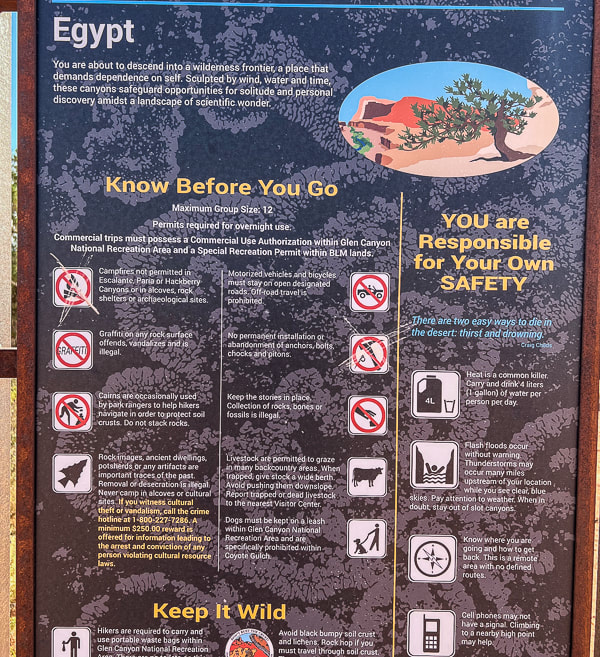

Imagining a Natural Catastrophe Still feeling energized after our Grand Canyon rim to rim hike, we decided to maintain our hiking fitness and get out of St. George's heat to hike a remote peak. I often go to Stavislost website to get ideas. Sandy Peak looked like a great opportunity for us to explore more of the forested Markagunt plateau near Cedar City, Utah. The rocks on Sandy's summit are just a microcosm of Earth's largest landslide - covering at least 1,600 square miles of southwestern Utah's high plateaus. It's called the Markagunt gravity slide, a catastrophic event that happened 20 million years ago when the surface of a huge volcanic field collapsed and slid southward for many miles, placing older rock on top of younger rock. "Markagunt Megabreccia" is the name of this rock unit. Breccia refers to jumbled angular rock fragments cemented together by a fine-grained matrix, with "mega' referring to fragments that are larger than one meter length. Catastrophic events like volcanic explosions create breccias. "Markagunt" is the Paiute word for "Highland of Trees". It resides in the Colorado plateau province. Cedar Breaks National Park rises from one of its highest points. Our Route: Avoiding the Steep Climb until it got Really Steep We parked just off the Old Spanish National Historic Trail in Upper Bear Valley. Locally, it is a nice graded road out of Paragonah that is also named Forest Road #077, Markagunt Plateau Trail and Bear Valley Road. 0 - 1.3 miles - walk southeast over Bear Creek right after parking, then walk up road (not numbered) that leads around the knoll to the east and drop into Ashton Creek at when it turns to the right (south). 1.3 miles - 2.9 miles - walk up Ashton Creek. 2.9 miles to summit - steep walk up Sandy's west slope, avoiding the top of the long ridge just to the north of the summit. We couldn't see Sandy Peak from the road approach. If I were to do this hike again, I would get out of Ashton Creek sooner and climb the first ridge on the left (east) I could see, which leads easterly to intersect with Sandy's north ridge. In the creek, we saw what looked to be a hunter's path (found a camera on a tree and a salt lick nearby) that led through a nice forest of pines, aspen and meadows, although we had a bit too many mosquitos. Getting on the ridge sooner out of Ashton Creek would have probably meant less bushwhacking. The steep walk to the top on Sandy's western flank was riddled with deadfall, rocks, and vegetation, adding to precarious footing at times. Maneuvering around rough volcanic blocks at the summit was fun. The view was huge. To the north, we saw smoke from a fire just south of the incredible Tushar Mountain range, and to the southeast the orange rocks near Bryce Canyon. This area of the Markagunt Plateau, squeezed up between Parowan Valley to the west, and the Panguitch Valley to the east has lots of trails, mountains, and mountain-bike friendly roads to explore. Gotta get back there! Visions of a Centro Woodfired Pizza got me through the last bit of route finding out of the creek. Per tradition, after hikes in this area, we went to this restaurant in Cedar City. Route-finding, wilderness, amazing view, pretty tough hike (at least for us), great pizza and great beer makes for the perfect day. Life is good! Caltopo Map and profile of our GPX tracks. North at top of map. Google Earth image of our tracks. Figuring out our route from Ashton Draw southeastward to Sandy Peak. Road leading southeastward from Old Spanish Trail (FR 077) toward Ashton Creek. This could be driven by a 4 x 4. Point where road turns right and we dropped down into Ashton Creek, 1.3 miles from where we parked. Sandy Peak not visible, but the long, lighter-colored rise just north of Sandy is poking out between two cone-shaped rises to the right of Fred. White columbine in Ashton Creek. Following cow paths in Ashton Creek until we found a wider trail (hunters' ?) that began on the right side of the creek to cross over to the left. Really nice hike up Ashton Creek, as long as you stay on the trail! Sandy Peak finally comes into view, but we were on the wrong side of the creek, so we went down and crossed, then went up the steep slope to the saddle just to the left of the peak. Looked like buck rub on these new aspens to us. Monument plant growing on slope with Sandy Peak at the top. The last time I saw Monument plant was on Mackay Peak in Idaho. Yep, it's a steep and rock-filled slope! Looks like layers of this volcanic mudflow breccia have separated or spalled from larger rock. Sandy Peak summit looking northward toward the Tushar Mountain range and a fire south of it. Descending into Ashton Creek, with lots of aspens. We are parked in Upper Bear Valley, at top of photo. Above this valley is Cottonwood Mountain to the west, where there are more trails. The East Bear Valley Fault runs the length of Upper Bear Valley. References

Biek, R.F., et al. Geologic Map of the Panguitch 30' x 60' Quadrangle, Garfield, Iron and Kane Counties, Utah. 2015. Map 270DM - The Utah Geological Society. Hacker, D.B., et.al. Catastrophic emplacement of the gigantic Markagunt gravity slide, southwest Utah (USA): Implications for hazards associated with sector collapse of volcanic fields. 2014. Geology vol. 42 #11.

2 Comments

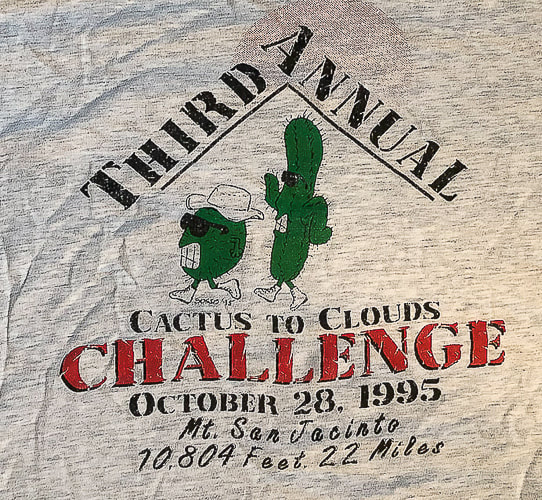

Standard route for Grand Canyon North Rim to South Rim in one day (North Kaibab Trail and Bright Angel Trail) Distances/Elevation gain/loss: North Kaibab Trail = 14 miles/5,700 feet loss. Bright Angel Trail = 9.4 miles/4,350 feet gain. Note: I've seen various estimates of "net elevation gain" that are higher. Since there is not any major regaining of lost elevation, I am estimating gain by difference between Colorado River and south rim. Elevations: north rim = 8,200 feet, south rim = 6,850', Colorado river = 2,500'. All Fired up! As Pat Benatar's song goes, we're "All Fired Up" for next week's Grand Canyon rim to rim hike! Her song is a fitting accompaniment to the goblet squat video below. Fred and I needed elevation training, so we went to Palm Springs, my old stomping grounds, and hiked the Skyline Trail for a gain of 4,700 feet, the same Bright Angel Trail gain on the south rim of the Grand Canyon. We encountered too much snow at 8,000 feet in the Pine Valley Mountains just to the north of St. George, preventing a good elevation gain. My last post, Grand Canyon Rim to Rim In One Day: Training in St. George, Utah, explains how we got creative with emulating distance and elevation. We did great on the Skyline; we're now ready for the big hike!

New goal: hike to the tram this October with some of our hiking buddies. Oh, the nostalgia and the beauty of this mountain! I'm grateful that I can still be hiking it 31 years later - let's say that the Advil this time was very helpful! La Verkin Creek Trail to Kolob Arch - Zion NP This long hike features attributes found in Zion National Park's main canyon, including an arch, sandstone cliffs and a river but without the throngs of people. It's in the northern Kolob Canyons section, has a spur trail to impressive Kolob Arch, and also meets up with the Hop Valley Trail, a route to the main Zion Canyon. We hiked 7 miles in to Kolob Arch and back for a total of 14 miles, the same distance as Grand Canyon's North Kaibab Trail. It drops down from the parking lot at Lee Pass Trailhead into the La Verkin Creek drainage. The same mileage as our Skyline Trail hike, but not nearly the same elevation gain. We've got one more training hike on Zion's West Rim Trail this week with Lindy and Jeff, and then we should be good to go for the Grand Canyon. We are lucky to have such inspirational places, some of the most beautiful on Earth, in which to train! Strengthening exercise for powerful hill climbing: Goblet Squats I have found that since I started doing CrossFit and working on strengthening my legs, I have more stability and power for steeper hiking. Goblet squats can be done with a kettlebell as well as two dumbbells, each resting on your shoulders. Strengthens your core (trunk) muscles, glutes and hips. Points to remember:

Forsyth Creek - Pine Valley Mountains in mid-May. It's a late spring here; ran into packed snow on the trail at 8,000 feet. Trees are just starting to bud. photos captured with my new Sony mirrorless camera. La Verkin Creek in Kolob Canyons section of Zion National Park. At the beginning of La Verkin Creek Trail - Kolob Canyons of Zion National Park. Jeff and Fred on La Verkin Creek Trail - Zion National Park. This morning was cold starting out - 31 degrees! Kolob Arch, 7 miles from Lee Pass on the La Verkin Creek Trail. La Verkin is the name of a nearby city between both entrances to Zion National Park. Origins for its name may have come from an alteration of the Spanish word for the nearby Virgin River -- la virgen. Mile #14 - on the way back to the Lee Pass trailhead! Beautiful Zion hike. Scott and Fred on the Skyline Trail overlooking Palm Springs and the Coachella Valley, California. Near the beginning of the Skyline Trail. Prepare before you go far on the Skyline! The steepest part is the "traverse" at the end of the hike. I have seen a person in serious trouble on one of our Cactus to Clouds hikes. Getting higher - overlooking Palm Springs. Oh beautiful yucca! At ~ 4,000-foot elevation on the Skyline looking at the final climb to the Palm Springs Aerial Tram on far ridge. One of the first views of the San Jacinto Wilderness, where the Skyline Trail that leads to the Palm Springs Aerial Tramway Mountain Station terminates on the ridge way up there! We are heading to the ridge on the right. Chaparral Yucca on the Skyline Trail with the Little San Bernardino Mountain Range across the Coachella Valley in the background. A good look at what is to come on the Skyline Trail. The tram station is just to the right of the arrow. Coffmans Crag, the white granite just below and to the right of the arrow, is a good landmark to see the final "traverse", a green and steep spot of trees to the left of it in this photo. The Skyline Trail is not one to be taken lightly. People have died on this trail. On one of our Cactus to Clouds hikes, a man caught up to us who had lost his hiking party. He was severely dehydrated - required a helicopter rescue. Left, right from top to bottom: Ribbon Wood tree (Adenostoma sparsifolium), Chaparral yucca, North Lykken trailhead sign, metal sign commemorating Jane Lykken Hoff, "trail boss" of the Desert Riders, contents of Rescue Box 1, Skyline warning sign, Rescue box 1, and boulder sign at the intersection of North Lykken Trail and Skyline Trail. Yucca and Ribbonwood trees. Celebrating long friendships with our hiking buddies in Palm Springs. I have known these friends for over 30 years! We have shared many miles on desert trails and many memories. Love you guys! from left to right: Scott, Vickie, Maria, Sue and Fred. Vickie, Maria and I are in the photo below - 31 years ago! The First Cactus to Clouds Challenge - October 1993

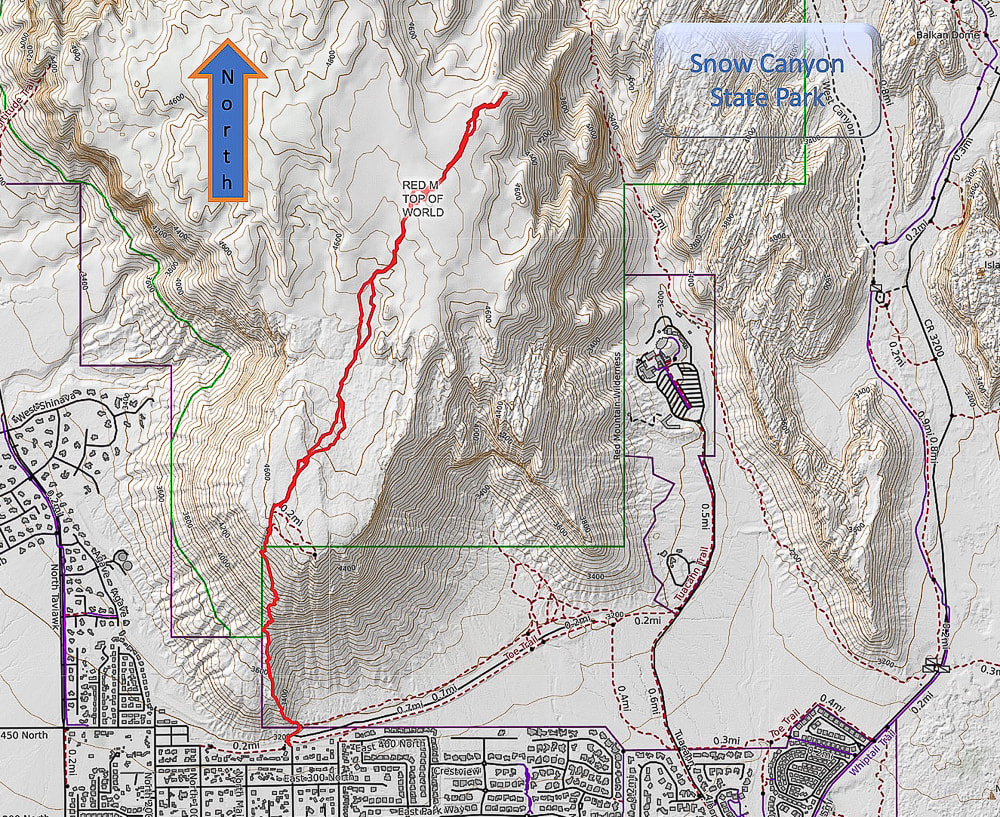

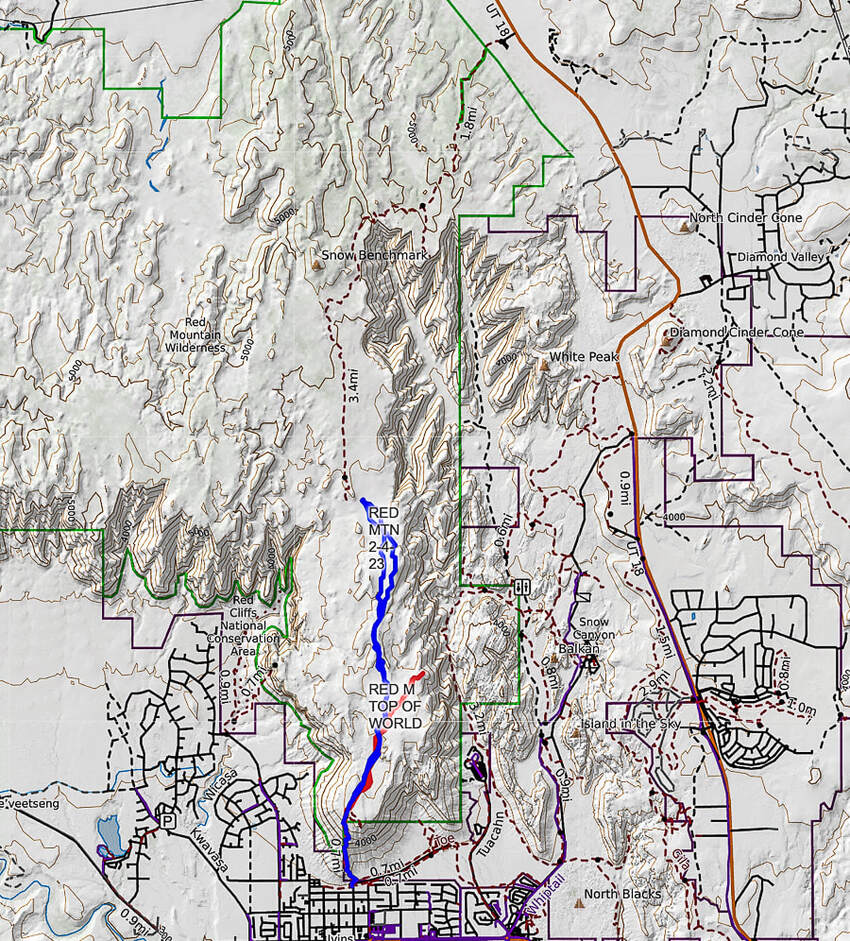

Summit of Mt. San Jacinto, 10,804'. From left to right: Sue Birnbaum, (don't remember his name), Roger Keezer, Maria Keezer, Ray Wilson, and Vickie Kearney seated in the middle. A New Year's Day 2024 journey through pinyon-juniper woodland on top of Red Mountain near St. George, Utah to a spectacular Snow Canyon overlook. Looking north over Snow Canyon State Park from "On Top of the World" on Red Mountain. Pine Valley Mountains on the horizon. View of Red Sands Trail (right) in Snow Canyon SP from a previous hike - Red Mountain Primitive Trail. Trip Stats - Ivins Trailhead

Overview/Location: This quiet, cross-country excursion through the gorgeous Red Mountain juniper woodland biome brings you to an expansive view of southern Utah's Snow Canyon State Park. A remote island of solitude in the Red Mountain Wilderness elevated above the cities of Ivins and St. George. Distance/Elevation gain: 5 miles out and back/1,575'. Coordinates/Elevation: Red Mountain Trailhead = 37.17519, -113.67755 (3,190'). Southern Red Mountain Primitive Trail out of Ivins. Top-off at 0.8 miles = 37.18375, -113.67849 (4,556'). Snow Canyon Overlook (On Top of the World) = 37.20116, -113.66671 (4,765'). Maps/Apps: Topo Maps U.S. app, Garmin GPS, BLM Utah Red Mountain Wilderness (Avenza app). Maps at end of this post. Difficulty/Trail: strenuous Class 1-3 climb up Red Mountain (mild exposure) for the first 0.8 mile, moderate cross-country Class 2 over slick rock and deep sand. Date Hiked: 1/1/2024. Geology: Red Mountain's lower slopes are the Kayenta Formation, the oldest rock in Snow Canyon State Park (190 million years). The horizontal sediment layers are made from rivers depositing mudstone, siltstone and sandstone. The upper slopes, cliffs and top of Red Mountain are a great block of Navajo Sandstone that is younger (180 million years), also seen as a major rock unit of Zion National Park. This Navajo Sandstone exhibits large, sweeping cross-bed features - horizontal and dipping layers of ancient sand dunes deposited in a vast eolian (wind carried) dune field. Red Mountain is bounded by the Gunlock Fault on its west side. It merges with an extensive field of 2.4 million - 2,000 year old basalt flows to the northeast. The Gunlock Fault is a normal fault with the down-drop on its west side (See references below). Considerations: The first mile from the Ivins trailhead is Class 1-2 with two short Class 3 maneuvers. Once the trail tops out, there is no marked trail. Experience with navigation and route-finding using a compass/GPS and topo maps is advised after top of Red Mountain is reached to avoid getting lost. A sign at this trailhead reads, "Hazardous, unmaintained route with steep exposed slopes: your safety is your responsibility." Recommend taking a GPS waypoint at critical points on the trail such as point where you enter the plateau from the cliffs. Search and rescue operations for lost hikers have occurred. Be prepared if you have to spend the night! Research this route thoroughly! 2/5/23: Three rescues in Washington County on the same Day (St. George News). Related Posts Our New Year's Day Hike Fred and I have a tradition of hiking on New Years Day. For 2024, we took friends to the top of Red Mountain and across its beautiful plateau to a high point dubbed "On Top of the World" by our friend Dan. From here, you stand 1,400 feet over an outstanding view of Snow Canyon's petrified yellow sand dunes and orange ridges, black basalt flows from northern volcanoes near Veyo. It's worth the orange sand trudge on the top to get there. This short, five-mile hike packs in a good variety of terrain. The first mile climbs steeply through a cliff band requiring some fun Class 3 (un-roped using hands to climb) maneuvers, gaining 1,300 feet. The next 1.5 miles initially descends through a beautiful juniper woodland bowl where Gunsight Pass can be reached to the southeast. You will trek through sand, washes, over slick rock then climb to a sandy saddle where our "On Top of the World" high point can finally be seen. Then it's a matter of making a ~0.5-mile beeline to it across relatively level terrain, traversing minor washes, dodging cacti and prickly shrubs. When you top-off onto Red Mountain's plateau, you initially follow the north/south Red Mountain Primitive Trail for ~1.2 miles, then a short jaunt off of it to the northeast to reach On Top of the World, elevation 4,765'. Red Mountain Primitive Trail's northern trailhead is located just north of Diamond Cinder Cone on Utah Highway 18. It's a fun little scramble to the cairned top, using your hands a few times to climb easy rocks, overlooking Padre Canyon and Tuacahn Center for the Arts to the southeast. Once you summit, the rugged terrain drops steeply below with a breathtaking view of Snow Canyon, with a few smooth slick rock benches above it that look interesting to explore or camp in. Can't think of a better way to celebrate the New Year: friends and the reward of finding our own way to a seldom-visited summit in one of the most beautiful places in the southwest. Great "medicine" for the soul, body and mind. Explore More in 2024!! Southern Red Mountain trailhead in Ivins. The trail starts out steep! Google Earth view of our GPS tracks beginning at the Red Mountain Primitive Trail's southern trailhead in Ivins (lower left), going through the cliff-band about halfway up, getting onto Red Mountain, and traversing across plateau to "On Top of the World" overlooking Snow Canyon, Padre Canyon, and Tuacahn Center for the Arts. See more maps at the end of this post. Utah yucca and pinyon pines, shrub live oak (Quercus turbinella) on Red Mountain's plateau. The name turbinella, meaning "like a little top", refers to the acorn, this plant's fruit which appears in summer. The reference to "turbinella" in the photo above prompted me to add these photos of the shrub live oak acorns. They're so cute! Life and death on the Colorado Plateau: beauty and grace in a dead juniper. On top of Red Mountain: lots of sand and shrubs to negotiate. The first view of "On Top of the World" highpoint (red cone to the right). Snow-covered Pine Valley Mountains on the horizon. This photo was taken last winter when we had record snowfalls in southwestern Utah. We have just walked across the pinyon/juniper scrub land behind Fred and Jeff and are starting up the ridge to our summit. Beaver Dam Mountains on the horizon to the west. "On Top of the World!" A cairn marking our summit and a view of Tuacahn Center for the Arts lower left. View is looking south at Ivins and St. George, Utah and toward Arizona on the horizon. Jeff and Lindy - Happy New Years! Dan (who named this summit "On Top of the World") in a photo from last winter. The road in the valley is the drive through Snow Canyon State Park. Note the black shrub-covered basalt flows mid/upper in photo, covering the Navajo Sandstone. Heading back. As soon as you get over the saddle in the foreground, you drop into sand dunes and washes, then a brief climb up a sandstone ridge to find your entry point onto the plateau. Navigation experience on unmarked terrain is essential so you don't get lost. I recommend taking a GPS point when you finish the 0.8 mile climb from the trailhead to the plateau entry. Heading down off the plateau of Red Mountain on Red Mountain Trail. Overlooking the city of Ivins. City of Ivins below. Descending through Class 2+/3 cliff band. Below us is the trail on top of the ridge. Caltopo Map of our GPS tracks. Caltopo map illustrating our hikes on the Red Mountain Primitive Trail. Red tracks = "On Top of the World" hike. Blue tracks = our hike on 2/4/23. Dashed line = continuation of Red Mountain Primitive Trail past Snow Benchmark, to intersection with Snow Canyon Overlook, then ending at its upper trailhead. References

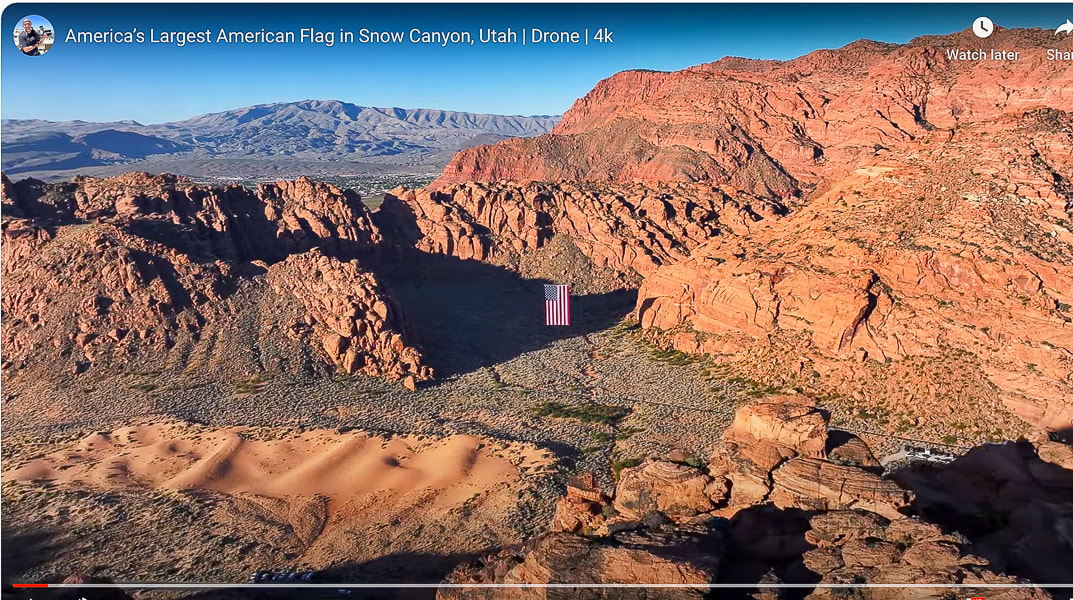

Bugden, M. Geology of Snow Canyon State Park Cryptobiotic Soils: Jayne Belnap. Holding the Place in Place - USGS: Impacts of Climate Change on Life and Ecosystems. Red Mountain Wilderness Maps - Wilderness Connect Ecoregions of Utah - usgs.gov Geologic Map of the St. George and East Part of the Clover Mountains 30' x 60' quadrangles, Washington and Iron Counties, Utah. Biek, R.F., and others. USGS publications. Miller, R. Our Geological Wonderland: Snow Canyon State Park A stunning sight on Veteran's Day: the largest American flag juxtaposed with the soaring cliffs of Snow Canyon State Park. Lady Liberty, displayed by Follow the Flag organization, at night in Snow Canyon State Park, Utah. Photo by Ann Little Related pages in Explorumentary: Follow the Flag Organization Facts

Check out awesome drone footage in these great videos! Saville Creations: America's Largest American Flag in Snow Canyon St George News Founders: Kyle and Carrie Fox

Motivation: To strengthen Americans' patriotism, a simple idea of inspiring, strengthening and healing people by hanging one of their huge flags in a canyon produced "far more impact than ever anticipated." Other events:

Mission Statement

American Flag Etiquette

Click on video below for awe-inspiring drone video

An unexpected sight greeted Fred and I on our favorite local loop-hike last month in Snow Canyon State Park. Just off Whiptail trail, suspended high in a gap between orange cliffs, hung an enormous American flag, seemingly out of place in in these walls of Navajo Sandstone. People were lined up, taking pictures of this spectacular sight. The flag, in the still air hung vertically, but billowed and rolled with occasional breezes, the bottom edge of it flying gracefully towards the sky. It was suspended in mid-air, with its hanging wires barely visible. I suppose you could ask what visitors were thinking about this huge flag in this gorgeous natural setting and you would probably get different answers, ranging from the emotion of national pride and patriotism to "Wow! That's pretty cool!" to "Why is it hanging here?" For me, my heart swelled because two things that I love were juxtaposed: a symbol of my country and the land of the American West.

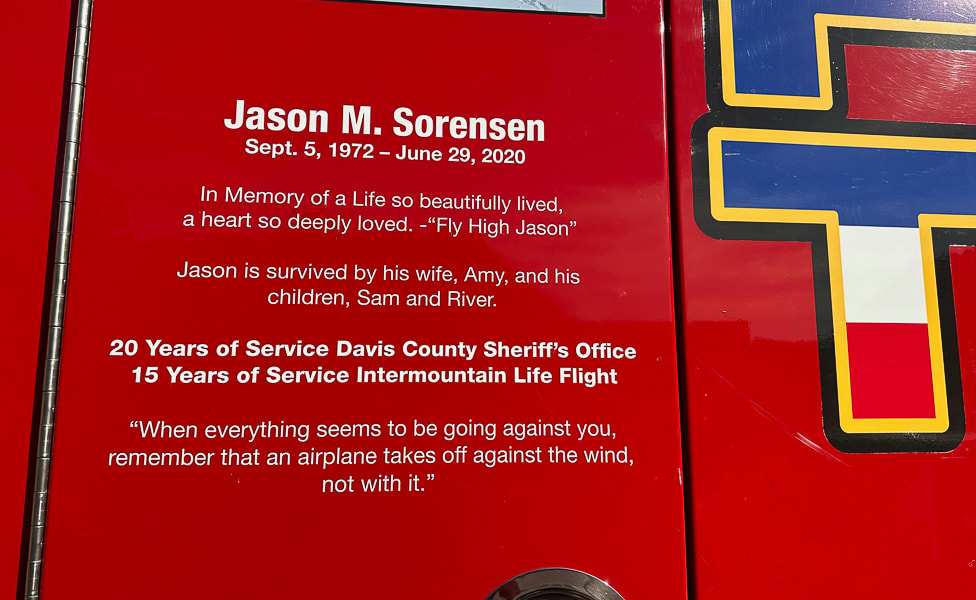

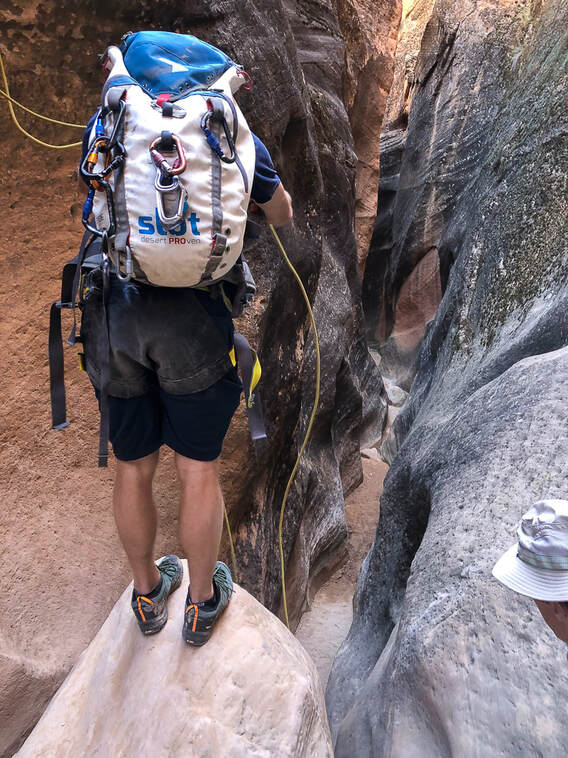

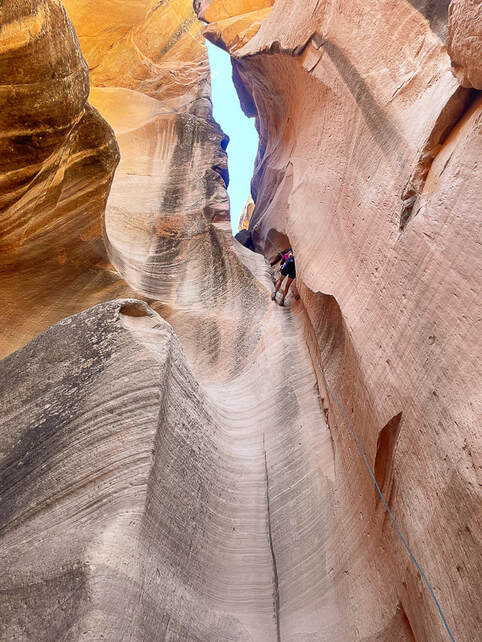

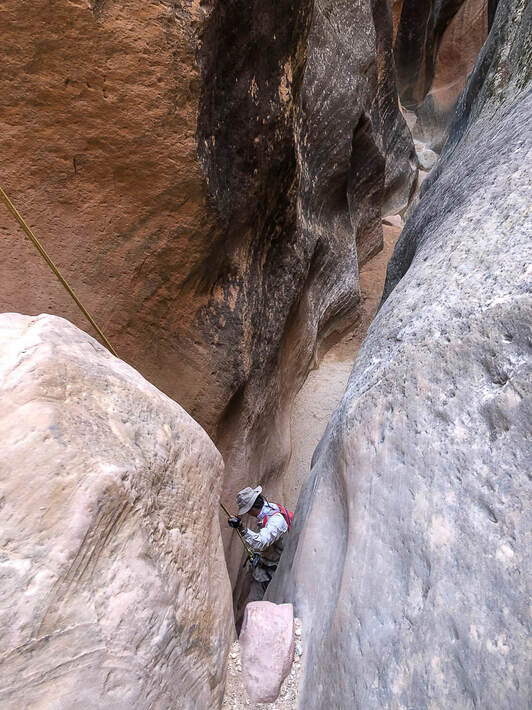

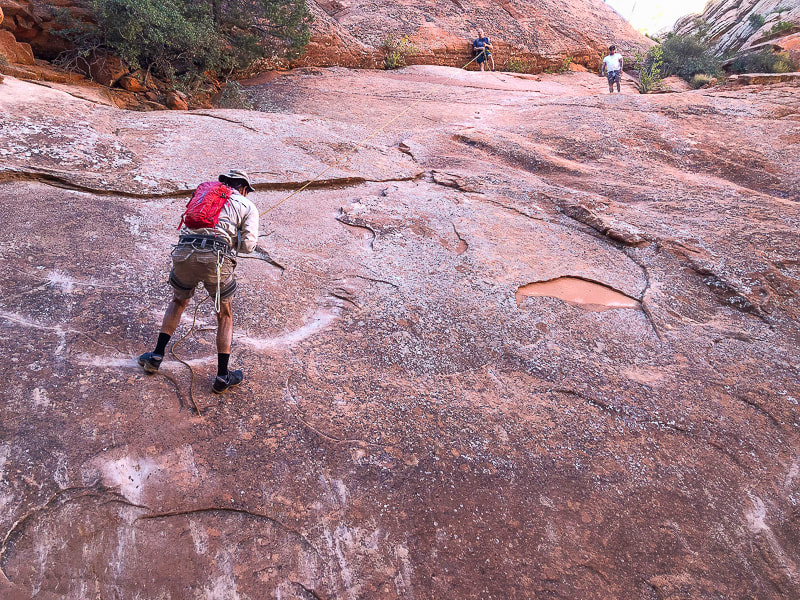

Strength, unity, connection, freedom - these are what the American flag is intended to signify. The stripes represent the original 13 colonies that were seceding from the British. The blue canton contains the stars of our 50 states. Blue represents vigilance, perseverance, and justice. White signifies purity and innocence, and red signifies hardiness and valor. This proved to be a good exercise in brushing up on my flag facts, reading America's unique Declaration of Independence, and learning of the efforts going on to unify our country. Pew and Gallup polls show that a record high number of Americans perceive the nation as divided on the most important issues. Maybe Follow the Flag and other organizations can help us see the positive and help us remember the ideals of our country's origin. "...if there’s one impression I carry with me after the privilege of holding for five and a half years the office held by Adams and Jefferson and Lincoln, it is this: that the things that unite us — America’s past of which we’re so proud, our hopes and aspirations for the future of the world and this much-loved country — these things far outweigh what little divides us. And so tonight we reaffirm that Jew and gentile, we are one nation under God; that black and white, we are one nation indivisible; that Republican and Democrat, we are all Americans. Tonight, with heart and hand, through whatever trial and travail, we pledge ourselves to each other and to the cause of human freedom, the cause that has given light to this land and hope to the world." - President Ronald Reagan's Independence Day Speech aboard the USS John F. Kennedy, July 4, 1986. A drop into the stained and polished Navajo Sandstone slot in this picturesque "beginner" canyon. Sue entering Yankee Doodle on first and longest rappel, ~ 75 feet. photo by Fred Birnbaum Trip Stats Location: Dixie National Forest - Pine Valley Ranger District - ~ 1 hour drive northeast of St. George, Utah, near Leeds. Date: October 15, 2023 Canyon Rating: 3A/B1 (Technical, Dry and Pools, short time). Distance: ~ 2 miles roundtrip (~ 0.8 miles in canyon). Access: from FR031, a 25-mile dirt road connecting St. George and Leeds: best traveled with a 4 WD with moderate clearance vehicle, as this road can get rutted and rough after a rain. The canyoneering portion is just south of this forest road. Start: 37.2361, -113.4528 Links: Paragon Adventure/Canyoneering/Yankee Doodle Hollow Rope Wiki Geology:

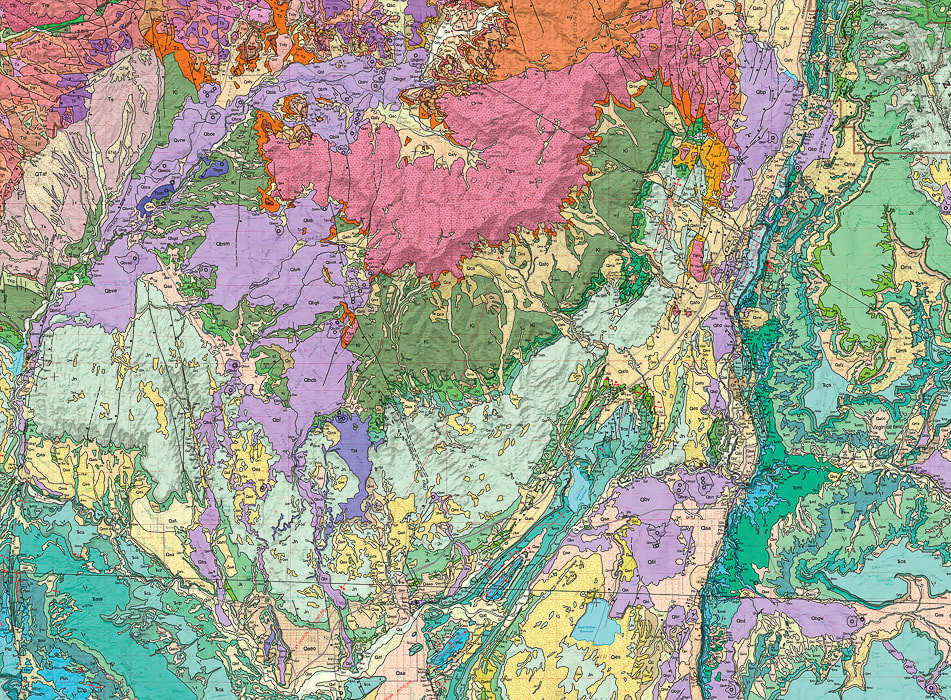

Related Posts Brian gets the ropes ready on the next rappel anchor. Our Trip This time Fred and I decided to "leap" out of our comfort hiking zone and try something more challenging: canyoneering! Although Yankee Doodle Hollow is rated as a "beginner" canyoneering hike, rappelling - especially the first drop into the canyon - was a challenge for us. This brief foray into these beautifully-polished and sinuous narrows rated as one of our favorites for 2023. Also on my list of favorites is the "Subway" - Left Fork of North Creek in spectacular Zion National Park, another journey into rock carved by water. My friend Brian from CrossFit Dixie has been canyoneering in this area of southern Utah, including Zion. He invited me on previous canyoneering trips but I was always too intimidated to go. He guided us on this short foray, setting up the ropes on the rappel anchors and instructing us on how to control the rope in our rappel device. He got us all set up with our harnesses and locking carabiners. Brian's friend Jorey, who had never rappelled before, joined us. The joy on his face when he completed the first long rappel into the canyon and overcame his fear of heights was priceless. He was so afraid to take the initial "leap" into the void. Fred and I had learned climbing techniques on a guided Grand Teton hike, but I was still pretty nervous. Canyon Origins Not sure how this canyon got its name. Was it named by miners in the area, or Mormon Leeds settlers? Yankee Doodle Hollow Creek originates from the highlands under the cliffs of the Pine Valley Mountains. This area of southwestern Utah is complicated geologically-speaking, with uplifts, gravity slides, compressional structures (uplift), extensional structures (faults), and more. One look at the Geologic Map of St. George area and you might agree. So many rock units from Permian time (300 million years ago) until present. Although a shorter and shallower canyon compared to legendary Zion canyons, Yankee Doodle Hollow still has the pretty curved and smooth cross-bedded walls of spectacular Navajo Sandstone - one of nature's works of art. You don't have to get a permit or arrange for shuttles between canyon entry and exit points, like you have to do in Zion. After we had completed all of the down-climbs we did a Class 3 steep slick rock scramble out of the canyon, slightly rubber-stained from many climbing shoes, as it opened up to the left. The Class 2 path up to the rim was discernible. If you keep going past this exit point, you continue walking down Yankee Doodle Hollow, you intersect with Heath Wash, where you would take a left (north) onto Heath Trail, which takes you back to FR031. Fun stuff! Glad Brian finally got me out there. Hopefully we can do more canyoneering....but Fred and I always default to the above-ground adventures! Thank-you Brian for getting us out of our Comfort Zone! Push the envelope - Keep on Exploring! A portion of the GEOLOGIC MAP OF THE ST. GEORGE AND EAST PART OF THE CLOVER MOUNTAINS 30' X 60' QUADRANGLES, WASHINGTON AND IRON COUNTIES, UTAH by Biek, R.F., et al. The pink rock unit at top-center of photo is Pine Valley Mountains (quartz monzonite laccolith). The Jurassic Navajo Sandstone is the light-green unit that presents as a kind of semi-circle around the base of Pine Valley Mountains, a much older unit, that is the main rock seen in Zion National Park. The City of St. George is located at the bottom of the map. We are going to be down there soon - WOW! Jorey (canyoneering newbie) left, and Brian on the right, getting us all set up. The first (and only) long rappel into the canyon, ~ 75', with two anchors. Photo by Fred Birnbaum Brian getting next down climb ready. Fred on a short rappel. Canyon exit: steep smooth sand stone on the left, fractured rock falls on the right. Pretty steep slick rock on the exit. Wandering around afterwards in Brian's RZR side-by side ATV. Pine Valley Mountains (monzonite porphyry laccolith) to the north. It's highest point is Signal Peak at 10,369'. Reference

Biek, R.F. 2010. Geologic Map of the St. George and East Part of the Clover Mountains 30' x 60' quadrangles, Washington and Iron Counties, Utah. Utah Geological Survey. Explore one of southern Utah's famous and extraordinary places - the enchanting "Subway" and its beautiful waterfalls. Walking into the "Subway", one of Zion National Park's iconic places. Trip Stats for bottom-up (non-technical hike)

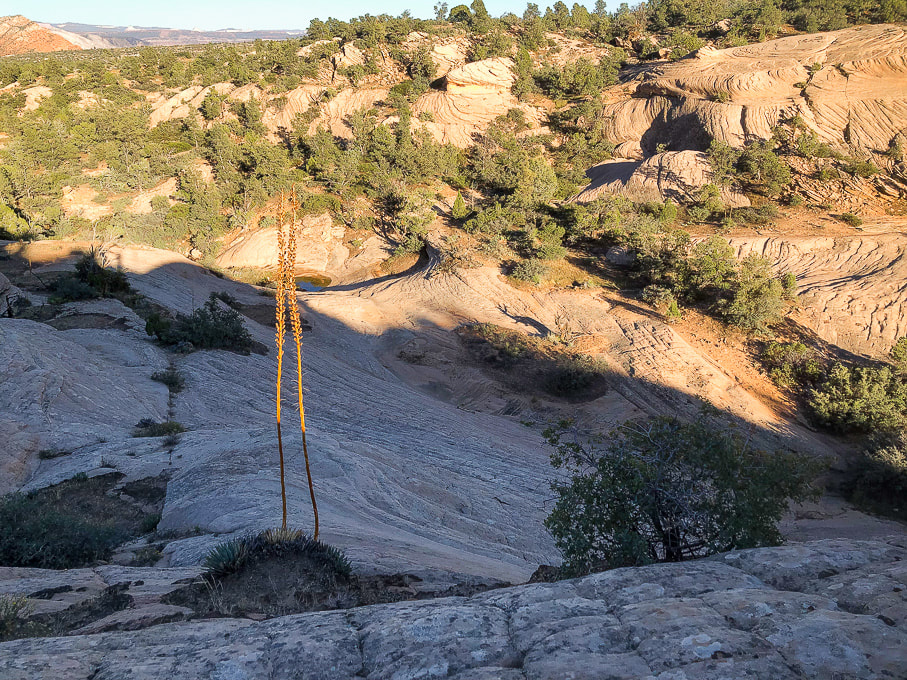

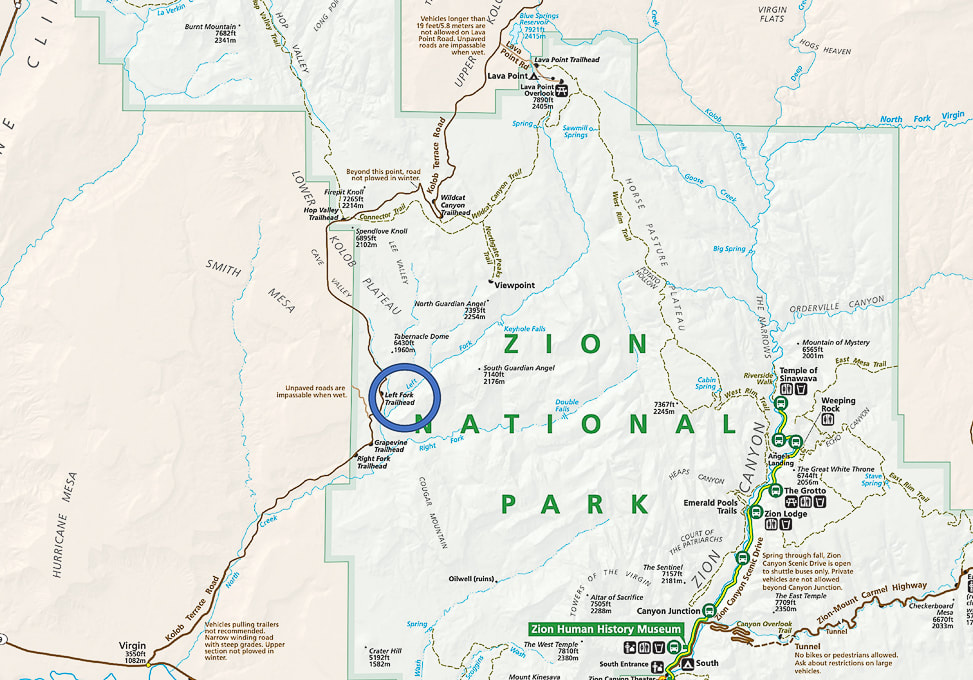

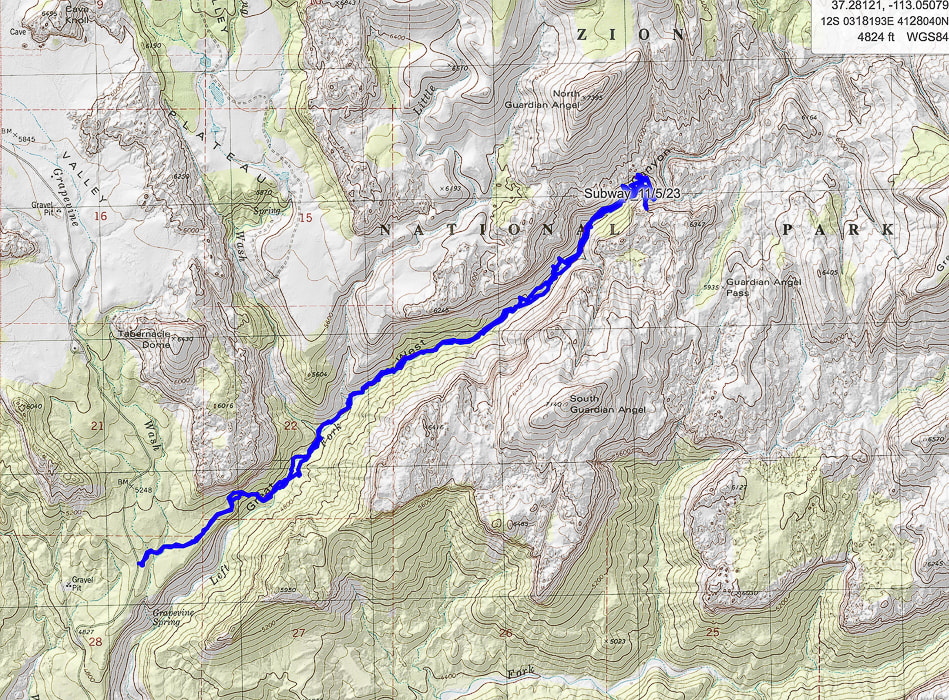

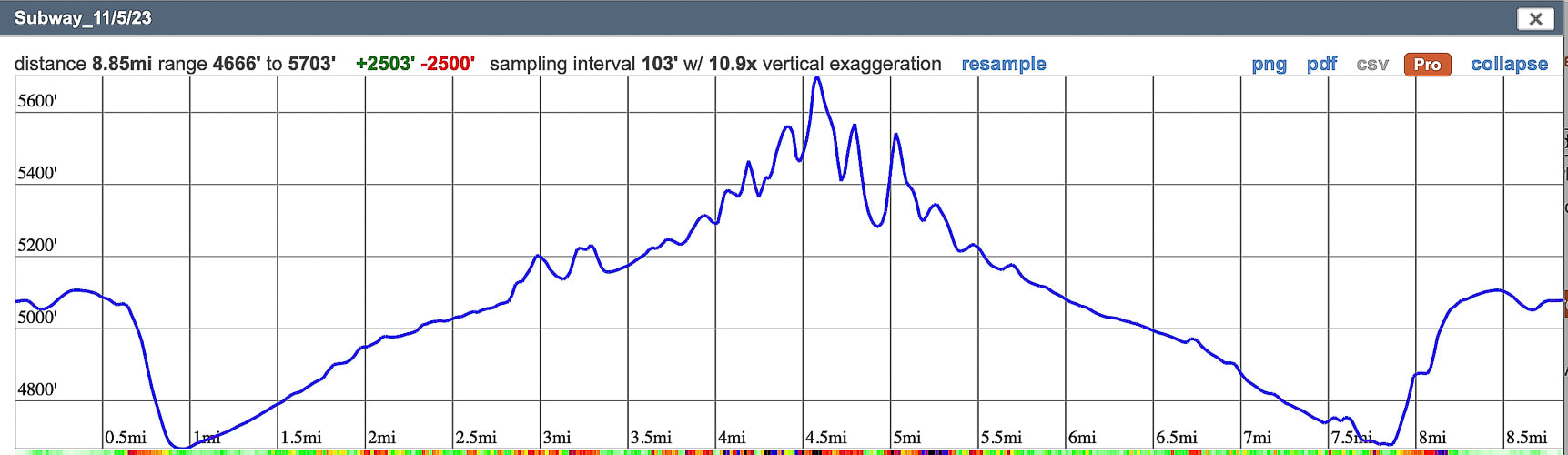

Location: Zion National Park - Kolob Terrace - Left Fork of North Creek Distance: ~ 8 miles out and back Difficulty: Moderate - strenuous boulder-hopping, stream wading and walking on slippery/uneven surfaces. Permit: permit required for all Left Fork/Subway hikes. Zion Wilderness Permits for Left Fork Subway. Date Hiked: November 5, 2023. Maps/Apps: AllTrails, Topo Maps U.S., USGS The Guardian Angels 7.5 min Topo Map Photo Advice: Summer: best light is mid-morning or mid-afternoon (pools are in full sun at mid-day). Autumn: mid-day is best light. Geology: Volcanic flow < 500,000 years from vent located north of trailhead: descend into Kayenta Formation (sandstone and mudstone). Navajo Sandstone towers overhead. Considerations: * Do not hike this canyon if there is a threat of rain/thunderstorms. * Make sure to take a waypoint of the canyon entry/exit and look at where you descended from the rim to get a good mental picture so you don't miss the exit point on the way back. There are signs but they may be easy to miss. Related Posts "The Subway" at the end of a four-mile hike from the Left Fork Trailhead. Waters over the millennia have carved out tube through this sandstone. This ultra-popular journey through Zion National Park's Left Fork of North Creek to the "Subway" and all of its gorgeous and calming water cascades - one after the other - exceeded my expectations and turned out to be a favorite hike for 2023. Having scored a permit only two weeks before, we were able to park in the Left Fork Trailhead parking lot (you have to put a permit tag on your dashboard), descend from Kolob Terrace to travel this stream to a magical world of green pools, red waterfalls and a tunnel of fern-covered sandstone walls. It takes about three miles of boulder-hopping and clear stream wading to get to the spectacular stuff, but it's so well worth it. I went with three friends who knew the route, and other friends who were seeing Subway for the first time also. The pathway up the Left Fork is pretty straight forward: it heads up-canyon, and around a major waterfall in about 3.5 miles from the trailhead. Much time is spent walking in the crystal-clear water. Less-Traveled Kolob Terrace: Beautiful Forests, Wondrous Canyons and Colorful Sandstone Peaks Compared to Zion Canyon, which received a record number of visitors - five million in 2021 - Kolob Terrace, Zion's west section, is a much-less visited area of Zion National Park. It's accessed via Kolob Terrace Road that ultimately ends at the Kolob Reservoir at an elevation of 8,100 feet - a marvelous place to see in autumn with the blue water and yellow cottonwood trees. A good list of adventures is posted in Joe Braun's Hikes in the Kolob Terrace. Kolob Terrace is also a great place for star-gazing and astrophotography. Zion NP became certified as an International Dark Sky Park in 2021. Das Boot is another classic Zion canyon on Kolob Terrace. It involves dark, convoluted narrows and long swims. If you prefer to be above the land instead of below, there are knolls named Spendlove, Cave and Tinaja to climb. Peak time on the Subway hike for fall color is late October/early November to capture the bright red and yellow leaves that fall in the round potholes and decorate the deep red sandstone cascades. Looking down into the Left Fork from the rim, yellow cottonwood trees line the bottom water course. The hike begins in a volcanic rock flow for ~ 0.5 miles from trailhead to rim, and in fact, it's important to note these black volcanic rocks on the rim when you get down into the creek, so you have a mental picture of the place you came down, and you don't pass it up on the way back out of the water. The 400' descent from the rim is steep and slippery in a few places. As you hike upstream, negotiating many pools, boulders and rocks, you occasionally catch glimpses of the magnificent Navajo Sandstone formations on the plateau above. We didn't pause too long because we had four miles of relatively slow hiking and the day was short. Amazing Place! And then you reach the almost supernatural world of the "Subway". Hanging ferns thrive on the dripping curved walls and round-sculpted lime green pools appear with water continuously pouring in and out. How did this stream sculpt this almost perfect tunnel? Crimson sandstone, polished by continuous water flow is slippery, I saw a few other hikers take minor tumbles. A few in our party waded through the cold deeper pools at the end of this section to a small waterfall. A few climbers with full wetsuits were descending from the Subway top down route which involves rappelling and deep water swims - the canyoneering route that begins further upstream. Sounds like a worthy goal for a future hike! Finding the point at which the trail leaves the canyon to ascend steeply to the rim was not difficult. I had the waypoint recorded on my GPS, so I knew we were getting close. Signs mark the way out of the stream, but it's best to remember the scene you memorized on the way in: the black volcanic rocks next to the orange sandstone on the rim. Grateful to be hiking in the American West - Keep Exploring! The Subway (Left Fork) hike is located west of the main Zion Canyon in the Lower Kolob Plateau. Left Fork Trailhead (blue circle) is 8 miles up Kolob Terrace Road. Beginning the descent into the Left Fork - looking forward to getting closer to those yellow cottonwood trees! Once into the canyon, the autumn colors are beautiful and the sandy trail is easy to follow. The canyon begins to narrow after ~ 1 mile and you get to walk by/through many pools past waterfalls. The shade, constant water flow, ferns and green pools create cool and calm. Lydia and Colin walking through the Subway. The end of the Subway hike from lower trailhead. You can walk in those gorgeous pools to a small waterfall. If you look at the middle of this photo closely , Lydia is wading in the cold pools! Archangel Falls The beautiful emerald pools in the Subway. Both images above: having fun with Photoshop oil paint filter. Google Earth map of my GPS tracks, beginning at Left Fork Trailhead, descending into canyon, and reaching the "Subway" after four miles. You pass under the North Guardian Angel and the South Guardian Angel (two peaks at end of this hike). My GPS tracks and elevation profile on CalTopo Maps.

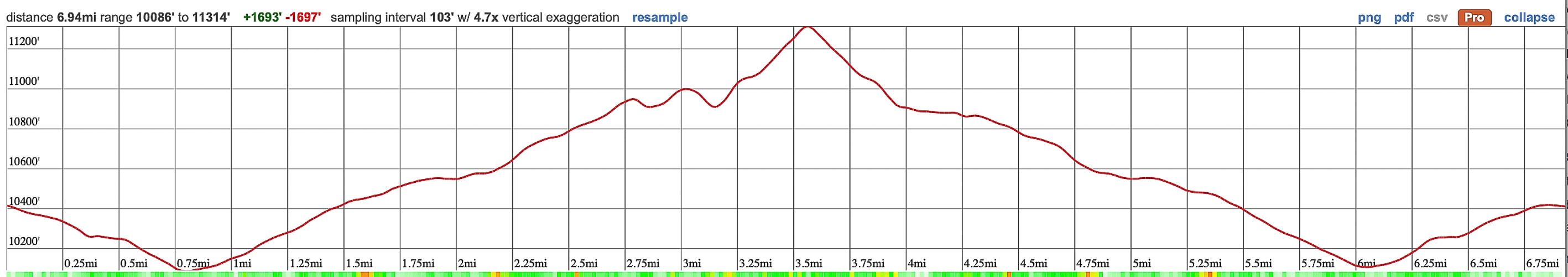

Note that the inaccuracy of GPS (extra-long lines that deviate away from actual hike course) occurs in a deep canyon because the GPS device cannot connect to all the satellites that are required to give an accurate position. This overestimates the hike distance. Walk across Egypt bench and wade through Escalante River in Glen Canyon National Recreation Area to a glowing grotto at the end of a luminous Wingate Sandstone canyon. Stunning Golden Cathedral at the end of Neon Canyon Erosion of Wingate Sandstone (Jurrasic, ~ 150-200 million years ago) over the millennia has created three skylights in this glowing grotto. Photographer Mish at Golden Cathedral. MishMoments.com photography website. Walking out through the overhanging walls of Neon Canyon. Trip Stats

Location: Southeast of Escalante, Utah in Glen Canyon National Recreation Area. Distance/Elevation gain: 10 miles out and back/~1,200' of gain. Mileage will vary slightly depending on if you take the standard route to Fence Canyon or the "Beeline" route. Difficulty: Moderate effort across pockets of sand; navigation off-trail moderately challenging. Coordinates: Trailhead: 37.59448 -111.22040. Neon Canyon opening: 37.60668 -111.16798. Trailhead: Traveling east on Highway 12 from Escalante, Utah, turn right onto the gravel Hole in the Rock Road a few miles out of town. Drive 16.7 miles, turn left (heading east) at the sign for "Egypt, 10 mi." Zero-out your trip odometer. Stay straight on main road. At 3.5 miles, cross Twentyfive Mile Wash. At 9 miles, a culvert identifies the Egypt 3 slot. At 9.5 miles, turn right at intersection. In ten miles park in large lot. It took us 1:40 from Escalante. Date Hiked: 9/26/23 Maps/Apps: Trails Illustrated Canyons of the Escalante #710, Alltrails, Topo Maps U.S., USGS 7.5 quad topo, Egypt, UT. Considerations: Do not attempt Neon Canyon if there is a chance of rain, and/or flash flood. Driving on road to trailhead requires moderate-clearance 4WD. Beeline Trail crosses Escalante River once. Too hot in summer months. Bring adequate water. Photo advice: Best time to photograph Golden Cathedral is between 11 am and 2 pm depending on the season. Most desirable to have the entire grotto in shade. Light from upper Neon Canyon reflects into the grotto creates glow on walls. At mid-day, light beams shine onto the dark green water on the floor. Links: Escalante Interagency Visitor Center (BLM) Earthline's blog post on this hike Escalante Petrified Forest SP Related Posts

Beeline Route Out and Back

Now I can see how Neon Canyon got its name. The colors are intense. Canyoneers rappel through the opening, getting access from a trail on its west rim. Stav is Lost website has a good canyoneering trip description of Neon Canyon. Fred and I got close to this remote marvel a few weeks before, but we heard thunder and saw clouds building when we got near Neon's opening, so we nixed the plan of going up this narrow canyon and headed back to the trailhead via Beeline Trail. On that hike, we checked out the huge petroglyph panel along the Escalante River, approaching from the Fence Canyon route. From the trailhead, identify Point 5270, a round dome to the east. That is your landmark to hike toward, as Neon Canyon is just to its left. The terrain that spreads before you is "Egypt," an elevated bench above the Escalante River, which flows right in front of Point 5270. The "Standard" Golden Cathedral Trail aims toward and travels along the north rim of Fence Canyon on the left in image below. The Beeline Trail goes in a more or less straight line toward Point 5270. A map of our GPS tracks hiking the Standard/Beeline loop is on my last post Neon Canyon/Escalante River Petroglyphs Hiking Directions. Looking east from Egypt Trailhead: Descend down through bowl onto Egypt Bench and make a Beeline toward Point 5270, the landmark just east of the opening to Neon Canyon. The alternate "Standard" trail heads to the left of Fence Canyon, seen at left in image.

Looking back up at Egypt Trailhead. The dark brown boulders are the landmark to look for when returning from Neon Canyon. They are from the Carmel Formation and made mostly of limestone. The underlying rock strata is Navajo Sandstone. Approaching the base of the Navajo Sandstone bowl and getting closer to the dome. This cairn marks the Beeline route. Cairns are few and far between and easily missed. Heading across Egypt Bench on trail that is discernible here and there. We saw footprints on the sandy Beeline Trail. The cleft with the large brown boulders on the plateau's rim is the landmark for the return hike. In September, abundant wildflowers speckled the hummocks and sand dunes. A definite trail through the sand. Longleaf false goldeneye? The beginning of the descent off the main Egypt Bench: stepping off of firm slabs of sandstone onto the soft deep sands of a lower bench or terrace just above the Escalante River. First really good view of the Point 5270 dome. Cottonwood trees fill the river bed. Neon Canyon opening is the notch under the dome. Not a problem descending this deep sand on the way to the river, but a pain to walk up it on the way back! Now we can see the opening of beautiful Neon Canyon. Just above the river bottom: the rounded rocks are a sign that the river probably once ran on this terrace. Nearing the cottonwood trees of the Escalante River bottom - would be great to see these when the leaves turn yellow! Weaving through brush and trees to the river. On the bank of the Escalante: switching from boots to trail running shoes. Only two short river crossings both ways, might as well keep boots dry for the hike. The canyon walls at Neon's opening and all the way through are stunning; trees growing against them seem small in scale. A path leads through a garden of wildflowers in September. A trail on the left side of the first bend in the canyon takes you above Neon's west rim and to the beginning of the canyoneering route. After a walk in the cool shade of Neon, reach Golden Cathedral in a little over a mile. We saw evidence of a recent flash flood in the fresh carved sand on the stream banks. The pool reflects the three skylights above. We stayed for awhile, appreciating the serenity, until the sun started to fill the canyon, shining on part of the grotto. The best time to photograph Golden Cathedral is before the sun hits it, so you don't get too much contrast. The reflected light from the upper Neon through the skylights is what gives the glow to these beautiful walls. With every Escalante visit, our to-do list grows exponentially in this land of remarkable personality. There's so much out there to explore! Intense colors near Neon's opening. A wide-angle shot of Neon walls. Fred walking out. Crossing through Escalante River back to Beeline Route. Carmel Formation (deposited ~ 170 million years ago) boulders strewn over Navajo Sandstone. Note the difference in textures: the limestone in the Carmel makes the rock more sharp and rough. Scenes from Escalante Petrified Forest State Park, where we stayed with our trailer.

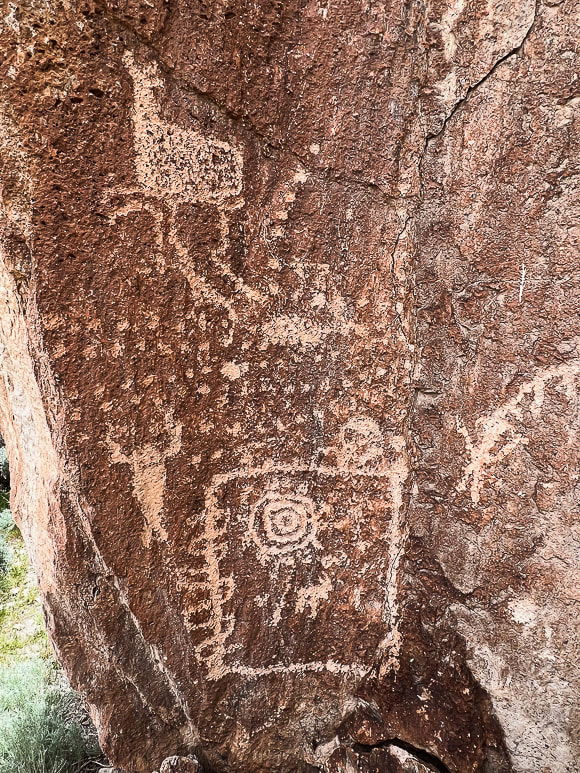

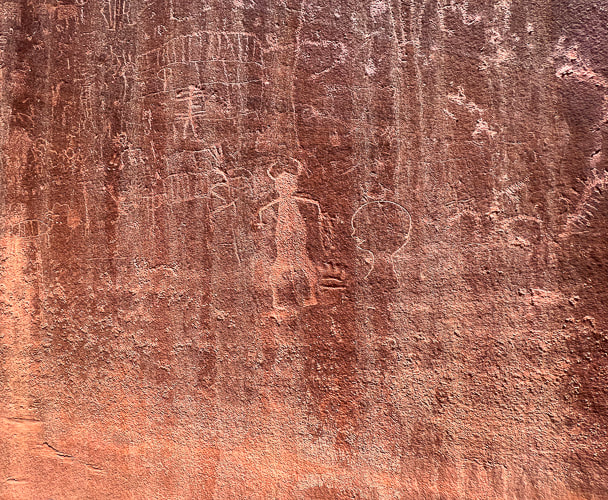

This prominent gap in the Red Hills has one of the most abundant collections of American West petroglyphs, including the most unusual of all - the Zipper Glyph.

Iconic Parowan - the "Zipper Glyph"

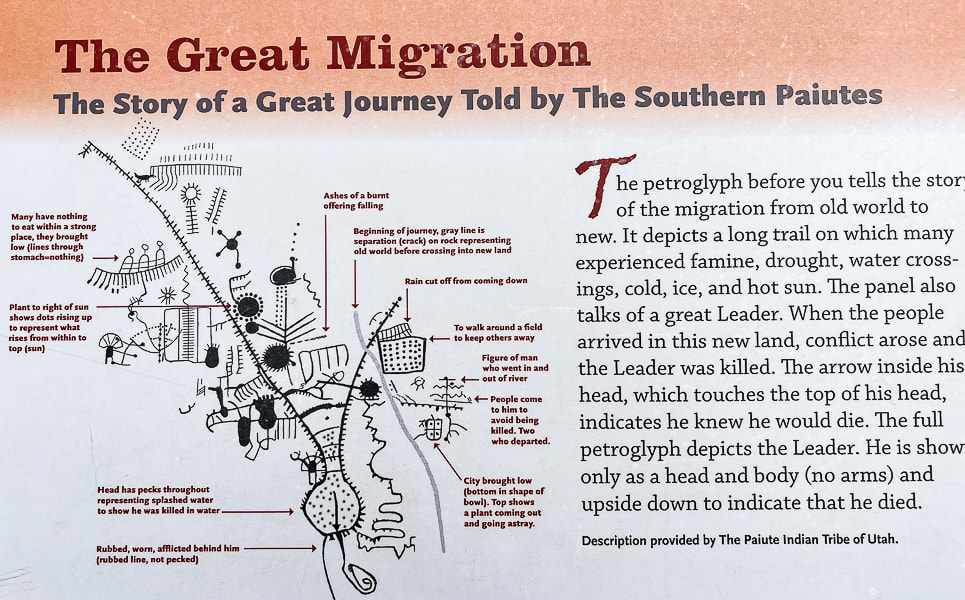

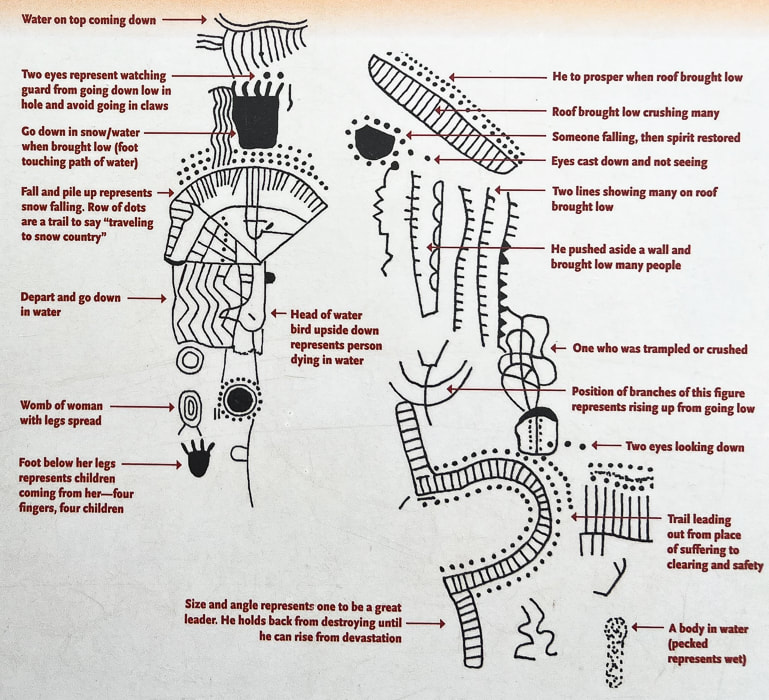

Interpretations of this petroglyph include a solar calendar because it has 180 notches coinciding with the 180 days it takes for the sun to move between summer and winter solstices. The Paiute Indian Tribe of Utah interprets this as the story of a great Leader during a migration where many people experienced famine, drought, water crossings, cold and ice.

Trip Stats

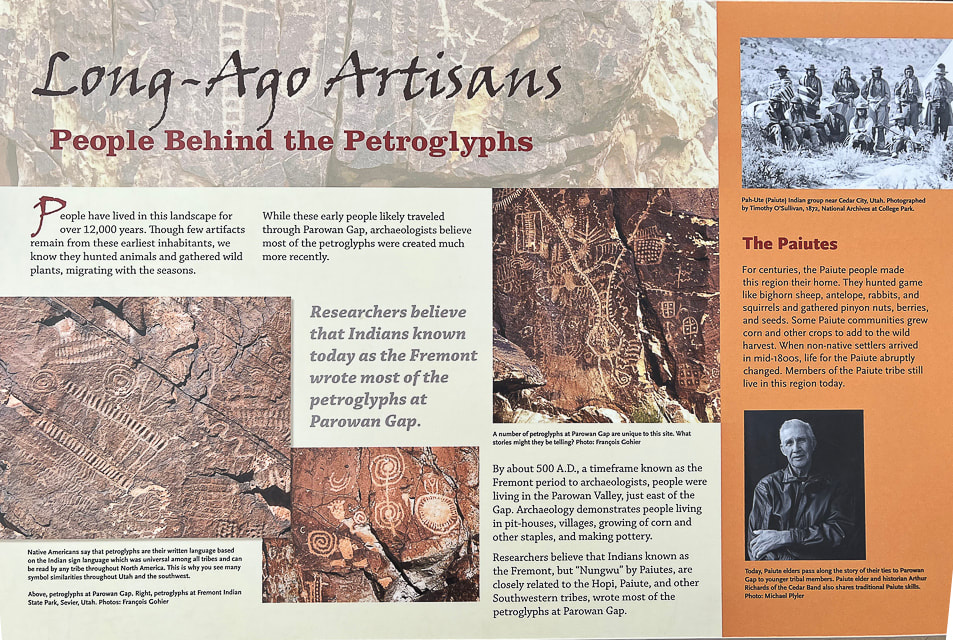

Overview: At the western edge of the Parowan Gap, in the "Narrows", over 1,500 petroglyphs made by different indigenous cultures are carved in the Navajo sandstone. Location: Parowan, Utah, just north of Cedar City, in the Red Hills west of Little Salt Lake. Petroglyphs are in the notch at the west end of Parowan Gap. Managed by Bureau of Land Management. Petroglyph Coordinates: 37.909722 112.985556 Native Americans: Fremont culture, Paiute, Hopi. Recognition: Listed on National Register of Historic Places. Geology: the petroglyphs are pecked into Jurassic Navajo sandstone, deposited 190 million years ago.

Related Posts:

Petroglyph "Heaven"

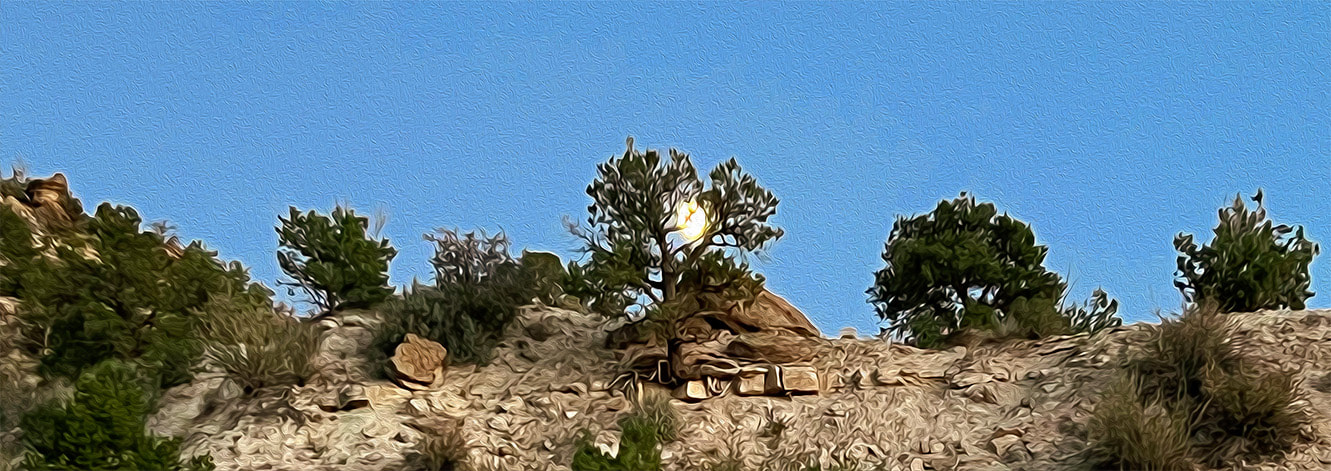

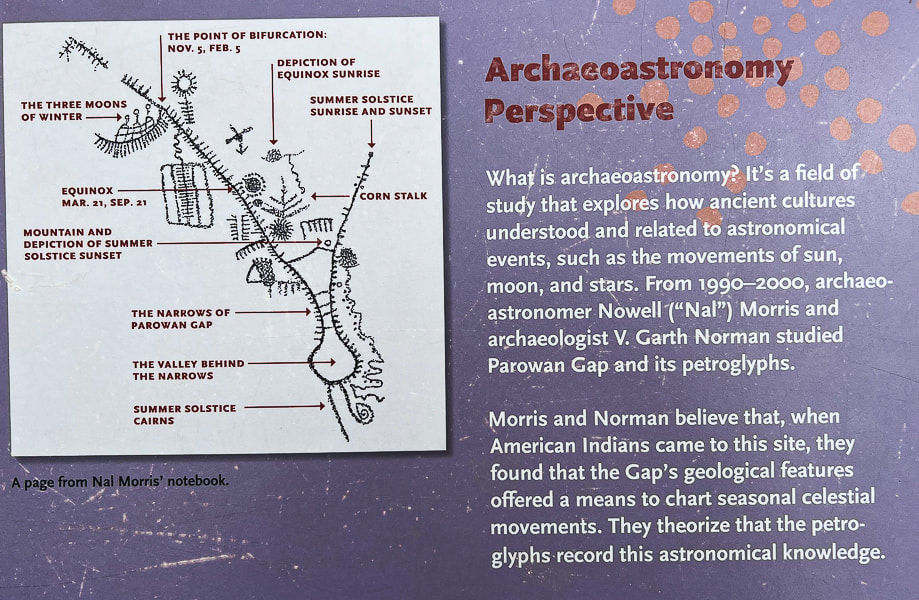

To rock art aficionados, Parowan Gap must be petroglyph heaven, not only because of its famous "Zipper Glyph", but also the amazing quality and number of petroglyphs there - rock after rock, panel after panel (90 of them!). Some believe that this site has the most concentrated petroglyph assemblage of any in the American west. Some of the rock carvings may be as old as 5,000 years, the majority of them made by the people of the Fremont culture. To today's Paiute and Hopi tribes, this is a spiritual site. The Parowan Gap is a stream-cut valley and narrows through the Red Hills, just west of Little Salt Lake, north of Cedar City, and 10 miles northwest of Parowan, Utah. The petroglyphs are located in a dramatic V-shaped notch at the western edge of this gap, a great place for indigenous peoples to carve their petroglyphs during their migrations. I was looking forward to seeing the Zipper Glyph in person. With two "arms" and 180 notches, people who believe in the astroarchaeological (AKA archaeoastronomy) interpretation see this mysterious petroglyph as a solar calendar. If you look closely at the Zipper Glyph, it resembles the notch in the Parowan Gap. It is believed that this glyph is a map with relating equinoxes and solstices. However, the modern Paiute Tribe of Utah had a different interpretation: a migration of the old world to the new. The Paiutes say that the Zipper Glyph represents a long trail of hardship in which their great Leader was killed. The two "arms" in this case are the Leader's body shown upside down with his head at the bottom.

An interpretive sign illustrating the belief that the "Zipper Glyph" was used to chart celestial movements.

Interpretive sign that describes the Utah Paiute Tribe's interpretation of the Zipper Glyph.

Parowan is nicknamed "the Mother Town of the Southwest." It's a city that has gone through a lot of changes since it first began mining iron in the 1800's. Now its main industries are tourism and recreation, including Brian Head, a year-round resort where we like to go skiing. It was first called "City of Little Salt Lake," because of its proximity to Little Salt Lake, a now salty playa to its west. It was renamed "Parowan," a native American word meaning "evil water." This lake is a key geographic feature relating to the formation of the Parowan Gap.

Fred and I had just hiked the astonishing Cosmic Ashtray in Grand Staircase-Escalante the day before, so we were on our way home. I had to talk him into seeing Parowan Gap; he doesn't normally want to go too far out of the way to see petroglyphs but with these he was pretty darn impressed. On the same Grand Staircase trip, we also hiked to a huge petroglyph panel along the Escalante River in Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, near the opening to Neon Canyon. Bear paws march up out of sight on this tall rock face, a rattlesnake slithers, and Fremont-culture warriors stand as just a few petroglyph examples. If you don't mind slogging through four miles of sand and slick rock, wading, and navigating, you can find these remote glyphs. It's believed that the Fremont culture made most of the Parowan Gap rock carvings 700-1,500 years ago, although the area has been inhabited for thousands of years before that. Typically the designs are abstract and geometric, although there are some lizards, snakes, and mountain sheep pecked into the Jurassic Navajo sandstone. Many petroglyphs are located very high, out of reach on the hillside. Check it out - you won't be disappointed! The interpretive signs make this a nice site. A great place to go afterwards if you are hungry is Centro Woodfired Pizzeria in downtown Cedar City.

Keep on Exploring!

For the Geo-curious: Creation of a Unique Land Feature

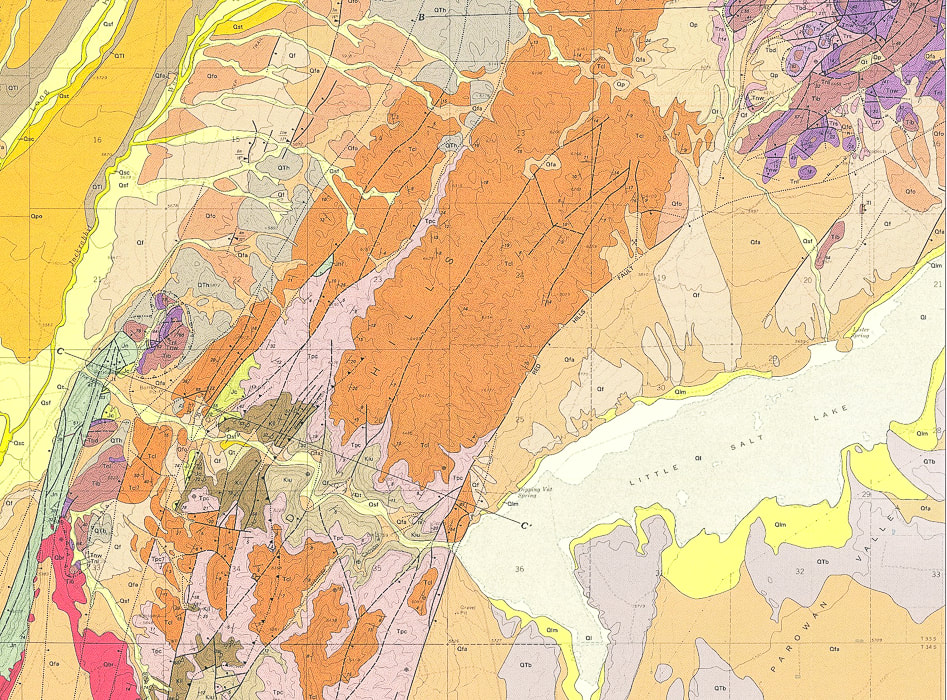

So, what created this peculiar notch in the hills — so noteworthy that ancient peoples over hundreds of years decided to engrave hundreds of petroglyphs as they migrated through the area? Two clues — the gap's rock orientation and Little Salt Lake help geologists to make sense of its creation. The ancient stream that for millions of years carved this gap through the Red Hills on its westward journey to the Great Basin became blocked by the rising Red Hills fault block. Its flow then accumulated to form Little Salt Lake, just east of the Parowan Gap. Either the fault block rose too quickly for the stream to keep incising through the rocks, or the region became drier and the stream had less volume, or both. Clues that faulting occurred are seen in the rock layers. North-south trending faults through the Red Hills caused east-dipping and west-dipping beds; some were left in their original horizontal position. The rocks here — Claron Formation (dominant Bryce Canyon rock), Navajo Sandstone (Zion's main rock), Carmel Formation, Iron Springs and Grand Castle formations first underwent mountain-building during the Sevier Orogeny 45-100 million years ago, when the Pacific tectonic plate collided and slid under the North American plate. The stream through Parowan Gap then carved a passage through the Red Hills. More recently, beginning 20 million years ago, Basin and Range extension (stretching of Earth's crust) began, which caused the Red Hills fault block to rise, blocking off the Parowan Gap stream's passage. Water collected to form Little Salt Lake, now a playa (a dried-up lake).

Geologic Map of Parowan Gap Quadrangle (USGS).

Little Salt Lake (lower right) was formed when the westbound stream that created the Parowan Gap (larger yellow, curving line (lower left) became blocked by the rising Red Hills. Note the parallel dark lines (faults) running mostly north-south and the long line extending from middle bottom to top right (Red Hills Fault), raising that fault block and providing a barrier to stream flow westward .

The "narrows" at the west end of the Parowan Gap. Ancient waters carved this opening in the Red Hills.

Extensive abstract petroglyphs on both sides of Gap Road, which passes through the Parowan Gap.

Interpretation of the panel above by Paiute Indian Tribe of Utah, from interpretive signs at the site.

Another Parowan Gap interpretive sign.

References:

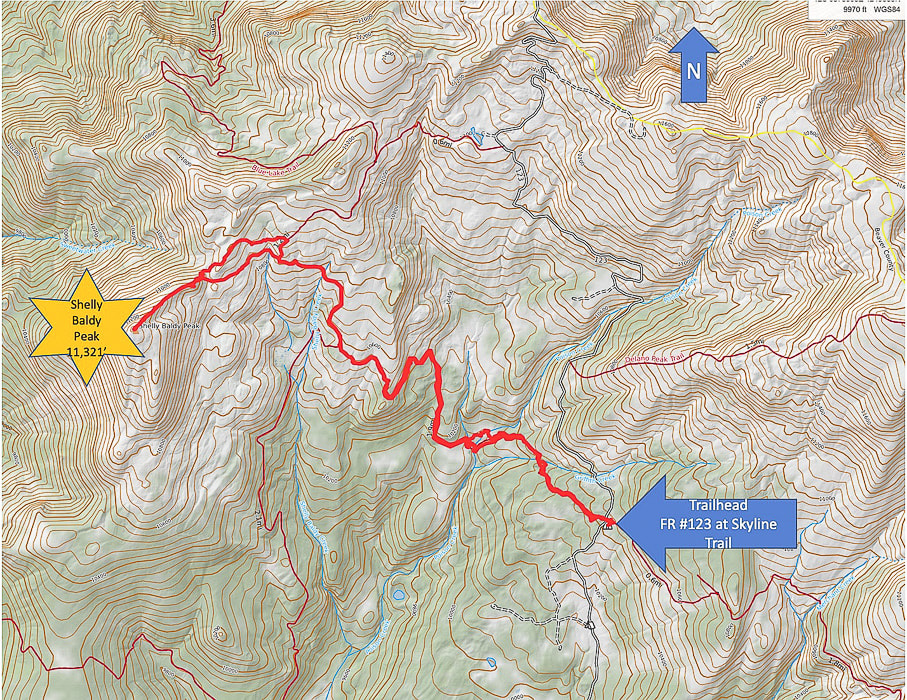

Maldonado, F., et al. Geologic Map of the Parowan Gap Quadrangle, Iron County, Utah. U.S. Geological Survey. Wilkerson, C. 2018. Geosights: Parowan Gap, Iron County. Orndorff, R.L., et al. Geology Underfoot in Southern Utah. 2020. Mountain Press Publishing Company. Parowan City Corportation website. Wadsworth, Rueben. 2019. Parowan Gap day; Interpretations and Mysteries of a Petroglyph Heaven. Cedar City News Archives. Hike a gorgeous and high Utah mountain range that relatively few know about. On Shelly Baldy's summit looking at Mount Baldy (left) and Mount Belknap (right), the Tushar Mountain's second highest peak after Delano Peak. Trip Stats Location: Southern Utah - Fishlake National Forest out of Beaver. Quick Summary (from Skyline/ Big John Flat trailhead on Forest Road #123, head northwest, ascend northeast ridge).

Difficulty: Easy - moderate Class 1, then moderate Class 2 scramble on stable talus ridge. Coordinates: Trailhead = 38.35910 -112.39317. Summit = 38.36911 -112.42528 Trailhead location: The Skyline-Big John Flat Trailhead is located 21 miles east of Beaver, Utah. From Beaver travel east on UT-153 road for approximately 16.2 miles. Turn left onto the FR123 (Sunset Drive) for 0.3 miles. Keep left on FR123 and travel another 4.5 miles to the Trailhead. Forest Service Interactive Map Maps/Apps: Fishlake National Forest - Beaver and Fillmore Ranger Districts map. Date hiked: July 26, 2023 Geology: Shelly Baldy summit is Mount Baldy Rhyolite, an extrusive igneous fine-grained silica-rich rock. Links: Mountain Forecast (weather) Fishlake National Forest Related Posts:

Descending Shelly Baldy's talus ridge looking toward the east and Delano Peak. Topo Map and profile for Shelly Baldy Peak accessed from Big John Flat/Skyline Trail trailhead. (Thank-you Caltopo). The Tushars: Ouiet, High, and Beautiful We keep returning to the less-traveled Tushars because of the forest, wildflowers, the variety of peaks to hike and the spectacular ridge scenery. And it's so green! We previously hiked Delano Peak, and a loop including Delano and Mt. Holly where we shared the mountain with the mountain goats. Copper Belt Peak was our original plan this trip, accessed along a beautiful ridgeline in the central Tushars, but we were blocked by a gate on the access road. We found out from a guy doing trail maintenance after finishing Shelly Baldy that there was still a snow slide blocking the road. Last winter (2022-23) saw record-breaking snowfalls in southern Utah. It's believed that Tushar came from the Southern Paiute word "T-shar", meaning "white". Mt. Belknap and Mt. Baldy, two of its highest volcanic-rock summits gleam white from a distance. Shelly Baldy is a fun peak and a not-too-difficult way to get stunning views of Belknap, Baldy and Delano. The hike is a combination of high-country creeks and waterfalls, meadows and forest, tundra and talus, and many wildflowers this July. The route is straightforward: you hike the Blue Lake Trail to its closest point near Shelly Baldy's northeast ridge and jump off to head cross-country towards it, having to negotiate a large talus field before embarking on a straight-up route on its ridge. It's a short climb on stable talus - not exposed - to the summit cairn, sign and mailbox that acts as a summit register. That night we stayed in the Mahogany Cove Campground, camping out of the back of our truck. We had driven up Forest Road 123 toward the trailhead the day before, but found all of the camping areas filled with RV's. The 275-mile Paiute ATV Trail, a network of trails and dirt roads runs through the Tushars. It ties together historic mining and native American sites, Mormon heritage sites, state parks and National Forests. Copper Belt Peak is still on our list. If we can't access it from Beaver, we can hopefully get to it from Marysvale, to the east. Comfort Kills In my Crossfit "box" (term affectionately used by Crossfitters to describe their gym which contains barbells, racks, rowers, jump ropes, kettlebells, etc.), a photo shows two athletes wearing shirts with the words "Comfort Kills." Intrigued, I read up on this "attitude." Forceful words, but they are true. We must go beyond our limits, our comfort zone. Going beyond what we think we can withstand, taking on risks in order to grow. "Our goal should not be to constantly remain in a sheltered place. Rather, in all circumstances have the ability to find solace." --Savage Gentleman website. I will keep on reminding myself. Growth and change happens in the extremes - Never Stop Climbing Mountains! Skyline/Big John Flat Trailhead just on FR 123. Some cool stuff on the trail. Griffith Creek near trailhead. Poison Creek - cold water and a bit tricky to cross! On the Skyline Trail walking out of the forest into higher meadows. Still on Skyline: first view of Shelly Baldy Peak with the two small snow patches near its summit. Intersection of Skyline Trail with Blue Lake Trail. From here we headed north (right) onto Blue Lake Trail. Blue Lake Trail: finding a point closest to Shelly Baldy's (peak with snow on it) ridge on the right. Looking for the best cut-off point from Blue Lake Trail. Looks like we found it. There's that big mound of talus to get over before heading up Shelly Baldy's northeast ridge. I think you could continue ascending Blue Lake Trail a little further and get off the trail to walk through the forest on the right and avoid so much of the talus. Faint trail through edge of forest. Hill of talus before reaching ridge. Wow! Pink!! Finally on steep, slippery ridge. Fred upper center. Pretty straightforward!! Mid-way up ridge looking at Mount Baldy, Tushar's third highest peak at 12,122'. At Shelly Baldy summit. Piece of cake! Looking west toward Mineral Mountains north of Beaver, Utah. On summit: Mount Baldy (left) and Mount Belknap (right). You can see why "Tushar" may have come from "T-shar," the Southern Paiutes' word for "white." Never tire of this beautiful forest. Reference

Cunningham, C.G, et. al. 1983. Geologic map of the Tushar Mountains and adjoining areas, Marysvale volcanic field, Utah. A four-mile journey across pristine slickrock brings you to this wondrous geologic feature in remote Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument. Nearby, a huge petroglyph panel representing various cultures looks over the Escalante River near Neon Canyon. The Cosmic Ashtray, aka Cosmic Navel - a huge 200-foot wide pothole filled with orange sand. Small sample of many petroglyphs on huge panel near the confluence of Neon Canyon and Escalante River.

Cosmic Ashtray The Cosmic Ashtray, AKA "Cosmic Navel" is an astonishing sight to behold after a suspenseful four-mile hike across a sea of slick rock, when it suddenly appears as a huge white sandstone pothole filled with deep orange sand, a large rock stashed inside it. This "weathering pit", also called "Inselberg (island mountain) Pit" because of its 10-meter high rock pedestal is the largest on Earth. It has erosional features that resemble similar discoveries on Mars. Wind continually changes the pit dune's orange sand shape and depth. Based on Colorado River erosion rates, a study estimates this pit is 216,000 years old. We talked to a bartender, a life-long Escalante rancher who had hiked Cosmic a few times. He has climbed into the pit sand by tying a rope to a shrub! We didn't find a hook in the pit wall. We got to talking about Hole-In-the-Rock Road, one of the few that gives access to Grand Staircase-Escalante and the Egypt trailhead we used for Golden Cathedral. After we complained that the road was very wash-boardy and rough, he said the county (Garfield) used to keep it in better condition before it became a National Monument. We've been down this road several times and this time it appeared to be in the worst condition. If you look at an aerial photo of the Cosmic Ashtray (check out the Netoff study), an open tunnel into the pit indicates wind has carved this channel smooth, creating wind-abraded flutes on its sandstone walls. Cosmic Ashtray is situated on a topographical high, between bedrock knobs. Wind funnels through these sandstone knobs enhancing wind speed (the Venturi effect). The orange dune sand comes from distant areas; it's larger-grained and therefore heavier than the sand of the eroded pit walls, so it accumulates in the pit. Fred hadn't seen photos of the Cosmic Ashtray weathering pit so he was amazed when we came upon it. The beautiful journey across miles of undulating bare Navajo sandstone makes you feel small and remote in the middle of the Jurassic-age buttes, knobs, and deep, narrow canyons. Moqui marbles, black embedded half-shells of iron concretions, and weird stained patterns pop up in the bleached and orange slick rock. Polygonal fractures that resemble honeycombs decorate the white sandstone all the way to the top. It will be fun to take friends next time without showing them a "preview" of Cosmic Ashtray just to see their astonishment at the sight of it. A sequence of ducks (small rock pile trail markers) led us up a steep pitch where Cosmic slowly came into view as we climbed to a lookout (Point 5847). At first, the northern-facing pit wall appears, followed by the tip of the pedestal rock in its center, and then finally its orange sand pit. Great vantage point for photos. Then you can climb back down and access the pit from its north entrance.

Deeply pecked abstract geometric petroglyphs from the Archaic culture (3,000 BCE) have been on this wall for so long that they are "re-patinated," or covered with dark desert varnish. Glen Canyon linear style anthropomorphs (resembling humans), and animals make up most of the glyphs. Bear paws and human feet march to the top of the slab. Ancestral Puebloans pecked bighorn sheep and broad-shouldered anthropomorphs during 1,000 BCE - 550 CE. We approached Neon Canyon from the Egypt trailhead along the "standard" trail which entailed three or four Escalante River crossings. BEWARE OF QUICKSAND when walking in low water levels. Our plan next time is to hike the Beeline route from Egypt trailhead to Golden Cathedral - this means only one river crossing near Neon Canyon entrance. With each Grand Staircase/Escalante visit, our list of places to explore expands as this spectacular ever-changing land seems to do. As I write this, I'm sitting in Las Vegas airport waiting for a Chicago flight. I keep thinking of the magnificent land of Grand Staircase-Escalante, feel a yearning to return to it. As its silty yellow and orange rivers flow, the scent of pine and juniper fill its air, and its landscape turns bright orange and vermillion with sunrises and sunsets, I wish I was there to see it. As always, so much to see and do, so little time.... Cosmic Ashtray Images The "Cosmic Ashtray" is an inselberg pit (insel = island, berg = mountain in German). The orange sand blows in from remote places. The center pedestal is ~ 10 meters high. Climb knob 5847 to the north for a good view of its sand dune. photo by Fred Birnbaum View of Red Breaks during first mile of hike. Vast juniper-dotted slickrock sea to the north. Indian Ricegrass haven and the Red Breaks. One beautiful reminder of life cycles in the slickrock desert. So many eroded Navajo sandstone features. Looking north toward flat "meadow." Potholes, tinajas, waterpockets, ephemeral pools are all names for these eroded sandstone depressions. Following duck trail markers to the top of Point 5847 that looks directly into Cosmic Ashtray. The "unveiling" of Cosmic Ashtray, aka Inselberg Pit from Point 5847. Moqui marbles and other weathered-out iron concretions making an interesting pattern. Movement of fluids through sandstones, especially Navajo Sandstone can create "bleaching" or removal of hematite (white bands). Neon Canyon/Escalante River Petroglyphs Looking down at "Egypt" from the trailhead. The route goes through alternating sand and slickrock. Aim toward the dark round dome upper left in photo - along the Escalante River. Neon Canyon's opening is at the base of this dome. I couldn't find the origin of the name "Egypt". This is an old stock route, so possibly an original rancher, upon seeing this wide, sandy bench said, "Sure the heck looks like Egypt!" Walking from Egypt Bench into Fence Canyon, which empties into Escalante River. Dropping into Fence Canyon, where a short hike leads to Escalante River for a short river walk. Short Escalante River wade before catching trail on right side of river. These abstract petroglyphs are more deeply incised and re-patinated (covered with desert varnish); they probably older than the anthropomorphic (representing humans) petroglyphs seen on left side of panel. Lots of petroglyphs superimposed over older ones. Some of the more recent are from cowboy Charles Hall in 1881, who made his cursive signature under the undulating snake petroglyph. These petroglyphs are located toward the left part of the panel and are lighter (desert varnish has not fully re-covered them), so they are probably made more recently than the abstract, re-patinated images. Hiking on Beeline Trail out of Escalante River, back to the trailhead. Petroglyph panel on left side of photo, Neon Canyon opening in notch below the round dome, aka Point 5,270'. Duck (left) marking the Beeline Trail back to trailhead. Related posts

|

Categories

All

About this blogExploration documentaries – "explorumentaries" list trip stats and highlights of each hike or bike ride, often with some interesting history or geology. Years ago, I wrote these for friends and family to let them know what my husband, Fred and I were up to on weekends, and also to showcase the incredible land of the west.

To Subscribe to Explorumentary adventure blog and receive new posts by email:Happy Summer!

About the Author

|