|

A rare chance to walk in water in Badwater Basin, attempts to climb Artist Palette Peak and Sheephead Mountain, and a wrap-up of 2023 hikes. Sunset on Badwater Basin, Death Valley National Park, 12/23. photo by Fred Birnbaum Trip Stats

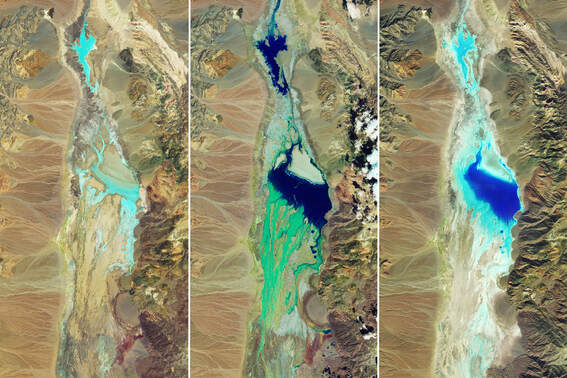

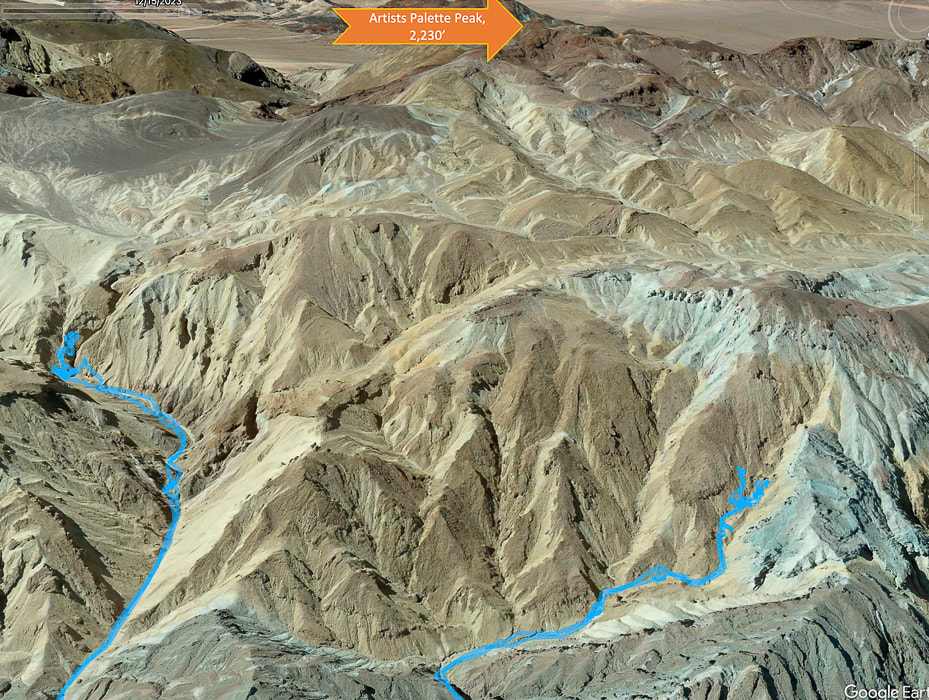

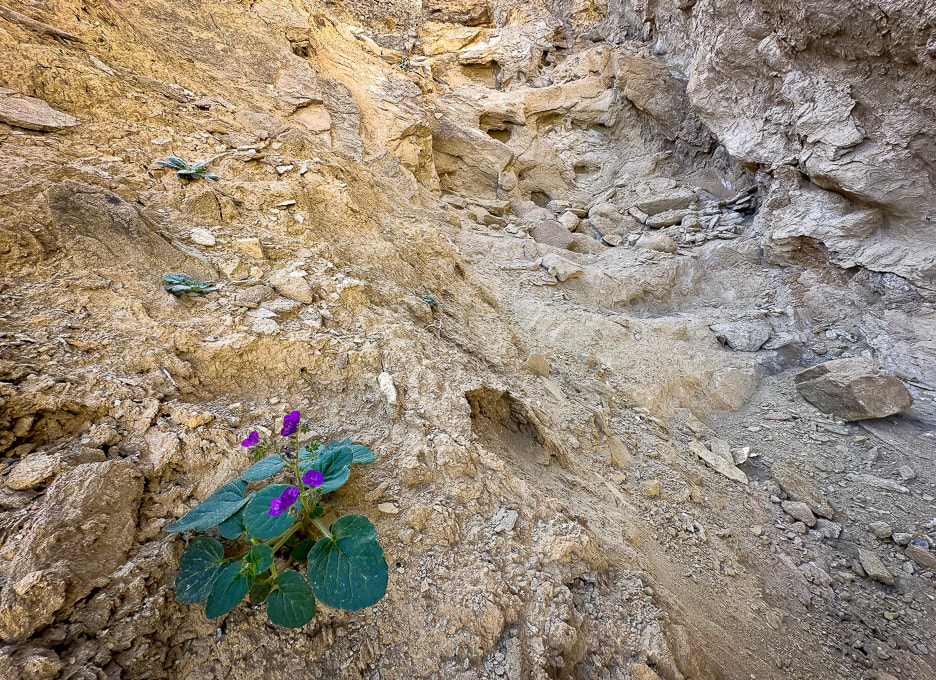

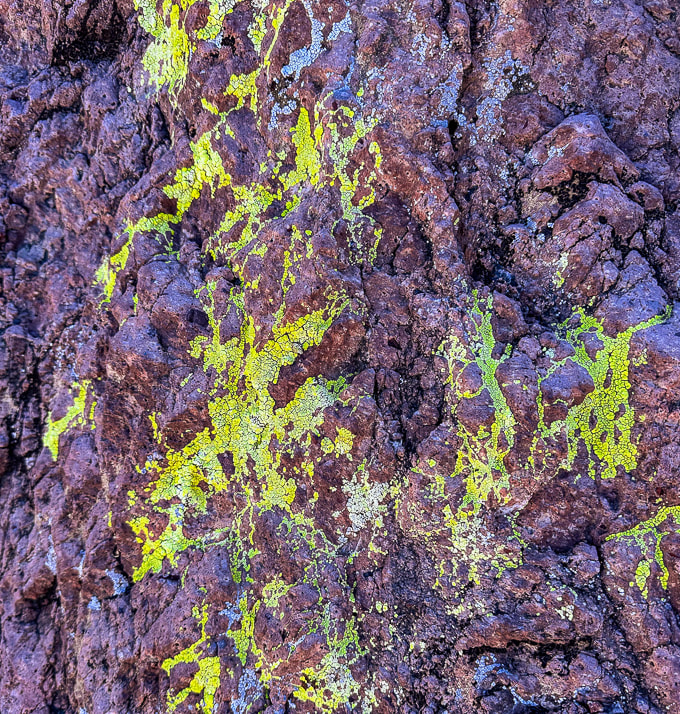

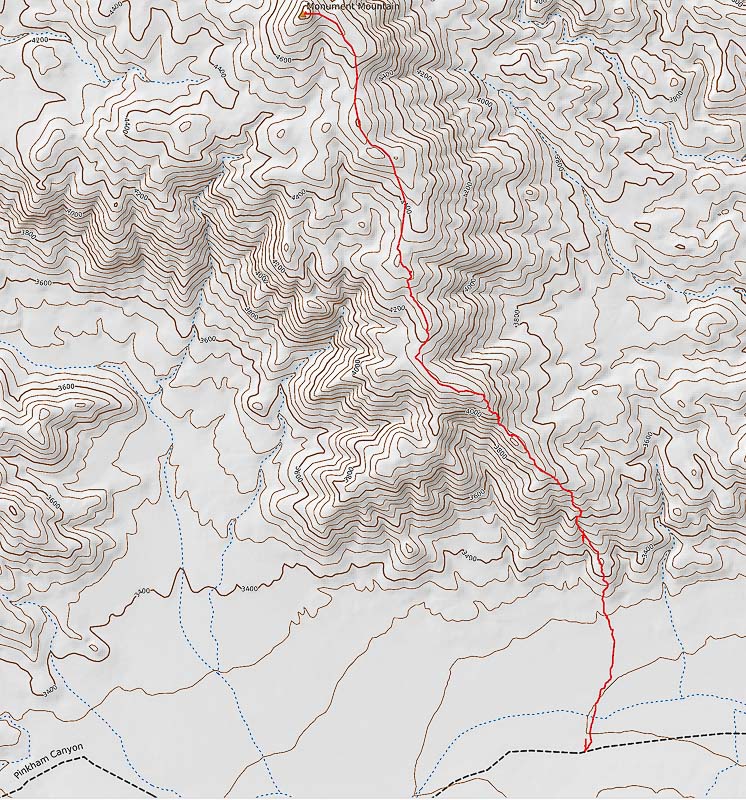

Peaks Attempted: Artist's Palette Peak, east Death Valley National Park, and Sheephead Mountain, Ibex Wilderness (southern Death Valley). Dates hiked: December 15 and 16, 2023. Maps and Apps: Trails Illustrated Death Valley National Park #221. Used Stavislost.com for Artist's Palette Peak and Sheephead Mountain routes. Lodging: Shoshone Inn at Shoshone Village, southwest of Death Valley NP. Geology: Tectonic processes relatively young; rocks are old Precambrian - 1.8 billion years ago. Schists and gneisses that have been uplifted and exposed, located in the Panamint Mountains to the west of Death Valley and Badwater Basin. Paleozoic - 550 million years ago. Limestone and dolomite in warm shallow seas. Late Paleozoic/Mesozoic - 225-65 million years ago. Pacific plate subducted under North American plate, causing melting ---> magma and volcanism. Jurassic and Cretaceous - magma chamber production ---> cooled intrusions that formed the Sierra Nevada mountains ---> some of these plutons spread eastward to Death Valley. Compression caused thrust faults (older rock thrust over younger rock). Cenozoic - 66 million years ago - present. Extension (spreading) caused volcanism Related Posts One of the photographers at Badwater Basin's lake. Our Trip - Badwater Basin, Artist's Palette Peak, Sheephead Mountain On August 20, 2023, Tropical Storm Hilary dumped a year's worth of rainfall on Death Valley National Park, transforming famous Badwater Basin into a spectacular sight: a huge turquoise-colored, salt-rimmed lake reflecting massive mountains on both sides. This rare occurrence is reminiscent of Pleistocene Lake Manly, a deep ice-age body of water that once filled this basin and dried up about 10,000 years ago. Although not as deep and extensive as its predecessor, it was still an amazing sight to see, especially at sunset. Badwater Basin, the lowest point in North America, is normally a salt flat cut into hexagons, and freeze/thaw hummocks - soft yet crunchy to walk on. Fred and I had hurried from Shoshone Village, a 45-minute drive to the southeast, to get there by sunset. There were a few other photographers, their mirror-images appearing unbroken in the still, shallow, and salty water. It was so quiet and remote that we could hear their conversations. For the past three years, we have stayed and hiked in the Death Valley National Park area during the Christmas holiday. In 2021, we hiked Pahrump Point out of Chicago Valley in the Nopah mountains with our friend Scott. In 2022, Fred and I hiked the awesome Pyramid Peak in the Funeral Mountains, and in 2023 we got to experience the magic of Badwater Basin's reflections and also hike Artists Palette Peak and Sheephead Mountain in the Ibex Wilderness. Hikes are challenging in Death Valley, a rough and rocky place - remote, stoic and mysterious. That's why we love it. A land that has experienced a lot of turmoil, yet stands defiant. How Long will Badwater Basin's Lake Last? The depth of the lake was about four inches where I stood after walking through thick (and sharp!) salt deposits at the lake margins. The evaporation rate in Death Valley is 120-150 inches per year. I read one source that stated the depth was two feet right after the storm. The evaporation rate is the highest in the U.S., so get out and see it soon! The Landsat images below show relative evaporation in 10.5 weeks (images 2 and 3). Note that the northern, smaller body of water appears to have mostly dried up already. National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Landsat Images of Badwater Basin in Death Valley National Park. Water appears in shades of blue. Image #1 taken 7/5/23 shows little moisture. Image #2 taken 8/22/23, two days after Tropical Storm Hilary's record rainfall. Image #3 taken on 11/2/23, 10.5 weeks after the flooding, shows some evaporation. NASA Earth Observatory images by Wanmei Liang, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey. Sodium chloride (table salt) crystals accumulated around the perimeter of this year's lake that filled in part of Badwater Basin, a rare event. This lake has the greatest evaporation rate in the U.S. Fred at the salty Badwater Basin, the lowest point in North America - a sublime setting. Artist's Palette Peak and Sheephead Mountain Our experience with gnarly-looking loose, slippery scree slopes (Idaho's Leatherman Peak is one) and Class 3 boulder obstacles made us turn back once we got closer to these summits. Both of these hikes involve Class 2 and 3+ route-finding, as there are no trails or markers. I frequently go to stavislost website to plan summits, and study topo maps to understand the terrain. Maybe we are, in our 60's, getting too old for these treacherous scrambles - or we just don't want to put ourselves through the frustration! Seems like we've had more "grudge peaks" than usual this year. Tough Terrain to Artists Palette Peak, top of image (looking south). Another Grudge Peak! Our GPS tracks in blue. Twenty Team Mule Canyon to the left, we ran into Class 3+. Steep and loose talus slope out of canyon to the right. We began ascending Artist's Palette Peak via Twenty Mule Team Canyon heading mostly south, after parking on 20 Mule Team Road, accessed from Highway 190. Evidence of a recent heavy wash-out with a freshly-carved stream (maybe from Tropical Storm Hilary?) coursed through the canyon floor. Huge boulders had been dropped into the canyon. We scaled a small waterfall and had no difficulty until we reached a Class 3+ boulder obstacle, blocking our progress. Shortly before this, we were able to hoist ourselves over a huge tilted boulder by standing on unstable rocks piled up against it to make a platform (glad I had Fred to help me place my feet in the right spot on these tippy rocks on the way down!). Hoping we were golden but discovering we were not after the next canyon turn, we tried a few ways to get past the next boulder array but decided to descend and try a different canyon. It would have meant climbing a very steep and loose slope of gravel, where I was slipping more than I was ascending. The canyon floor had signs of a recent wash-out. Twenty Mule Team Canyon Toward the top of Twenty Mule Team Canyon - we were able to ascend this narrow, wobbly stack of rocks to hoist over this boulder but then met up with Class 3+ moves after this that proved too intimidating. The obstacle in the above photo is where another Artist's Palette Peak hiker who recorded his trip on Peakbagger website turned around. Stav Basis, in his route description of this hike advises that if you are hiking Twenty Mule Team Canyon to ascend it rather than descend it to make sure you can maneuver the Class 3+ stuff and you don't get stuck. The next canyon we attempted to the northwest of Twenty Mule Team Canyon had footprints in it, possibly from a group of hikers we saw at the trailhead. We followed it, fun scrambling over easy walls, until we were diverted out of the canyon to see a steep and loose talus slope with no end in sight. It's frustrating to know that "obstacles" like this get in your way of seeing your intended peaks and knowing there was less-steep terrain above. But that's why off-trail route finding in Death Valley is so rewarding - you have really earned the view from the summit and the access to the peak register. There is no other place like Death Valley's terrain - mostly devoid of vegetation. Rocks and sky predominate, but sometimes you get a remarkable surprise, like the blood red and magenta Desert five-spot flower growing in the gravel (photo below). Conglomerate boulder containing mostly rounded cobbles from long-ago streams. Desert five-spot Eremalche rotundifolia Route up canyon on the right - fun scrambling. Looking down a "rock ladder" we climbed from the canyon floor. Shortly after this we came to the steep and long loose talus slope and decided to turn back. Sheephead Mountain (13 ascents on Peakbagger - A Sierra Club Desert Peaks Section Peak) I had been looking forward to hiking in the Ibex Wilderness, so the next day when we hiked to Sheephead Mountain, we were remote and alone, except for the occasional motorist on Highway 178, which begins at Shoshone, then heads west through two passes to turn north as it becomes Badwater Road, hugging the east side of Death Valley. We parked in a pull-out at Salsberry Pass, about 12 miles from Shoshone. The faint trail that headed southeast toward Sheephead soon became non-existent, so the approach was a maze of red washes and rubbly hills. We located our daunting-looking mountain to the south. We ascended a rotten, slippery and steep ridge of yellow scree too soon. Once we got on top of this yellow high point, we realized it would have been easier to ascend the red ridge just to the south, leading more directly to the saddle on the final ridge to Sheephead, which looked like a tower with more loose scree slopes flanking its sides. We didn't have the motivation in us to attempt the rock piles. From the saddle we found an easier way down over a ridge and then dropping into a wash. We instead walked back to the highway, crossing it and wandering on a ridge toward Salsberry Peak, seeing occasional bighorn sheep signs. Wrap-Up of 2023 hiking - The Year of Grudge Peaks This year we did more remote desert route-planning and finding on unmarked terrain with no trails in Utah's Zion Wilderness and San Rafael Swell, Nevada and Death Valley. Occasionally we see cairns that let us know some other hardy souls had stood in the same place. Walking without a trail takes more time. As a result, we had more "grudge peaks" this year - ones where we did not make the summit. Mummy Mountain was the most frustrating; we were within 200 feet of the summit and ran into a deep and steep snow-filled gully with no great footing to get out of it to a narrow shelf to the top. Scott, Fred and I will hopefully try this summit again but from the more-used trail on other side of the mountain. Other "grudges" this year were Hepworth in Zion, and Bearing Peak in Lake Mead National Park. Moapa's knife's edge we're not sure we would attempt again. Successful summits included Shelly Baldy in the Tushars, Mt. Kimball in Tucson, Jackson Peak near Boise, and Burger Peak in Pine Valley Mountains. And, the summit of Angels Landing was sweet because we got to hike it with my sis and bro-in-law. One of my favorite authors, Willa Cather famously said, "The road is all, the end is nothing." As far as reaching summits, I would have to respectfully disagree. The way to the summit is a great experience, but to stand on the summit after you've worked hard to climb it is even sweeter. So, is it our age or the pursuit of more technically challenging hikes that are preventing us from reaching our goals? I like to think it's a little of the first and mostly the last of those two reasons. Should we focus less on goals and more on appreciating just "being out there?" - not to always define "success" as achieving a summit? Of course, I love being out there in our American West, but my goal-driven trait wants more. At any rate, it's been fun to try something different and work on navigation skills in more remote country. I count myself as one of the lucky ones who gets to even consider this conundrum in the first place. Keep On Exploring! Walking southeast toward Sheephead Mountain (with notch on horizon 1/3 in from left). Sheephead Mountain on horizon to the right. The loose and steep yellow scree slope we ascended, but didn't descend. Reaching the top of the yellow scree slope and the ridge leading to Sheephead Mountain. Ridge leading to Sheephead Mountain. We descended down the red slope to the right. Fred at top of yellow ridge. Sheephead on horizon! Looking southwest toward Talc Hills and Black Mountains. On our descent over red rocks - looking at our ascent over the not-so-fun loose yellow rock. Looking toward the northwest. Parting shot - the ascent (Sheephead on the right) looks manageable from here! Bright cobblestone lichen? A few more images near Zabriskie Point in northeast Death Valley National Park... References

Fish, N. From Indiana University. https://sierra.sitehost.iu.edu/papers/2008/fish.html Doermann, L. NASA Earth Observatory. Floodwaters Fill Badwater Basin. Hunt, C.B., et al. 1966. Hydrologic Basin Death Valley California. Geological Survey Professional Paper 494-B.

2 Comments

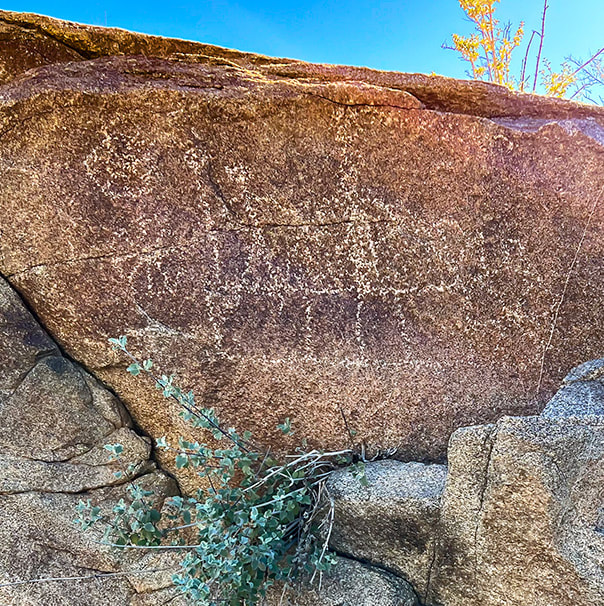

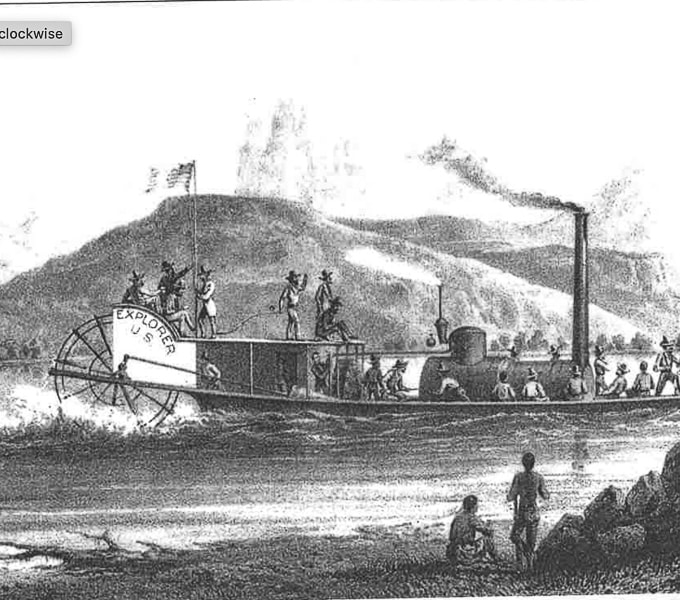

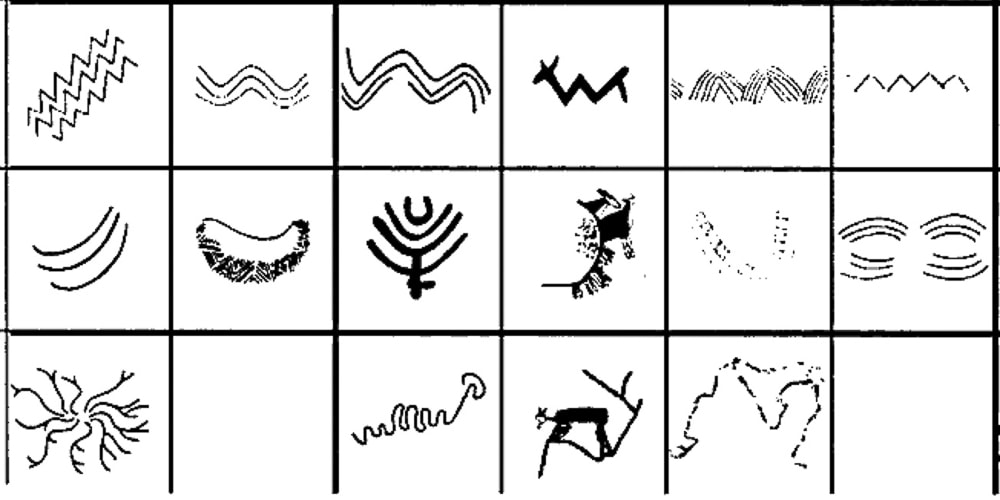

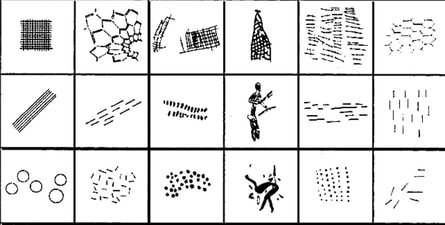

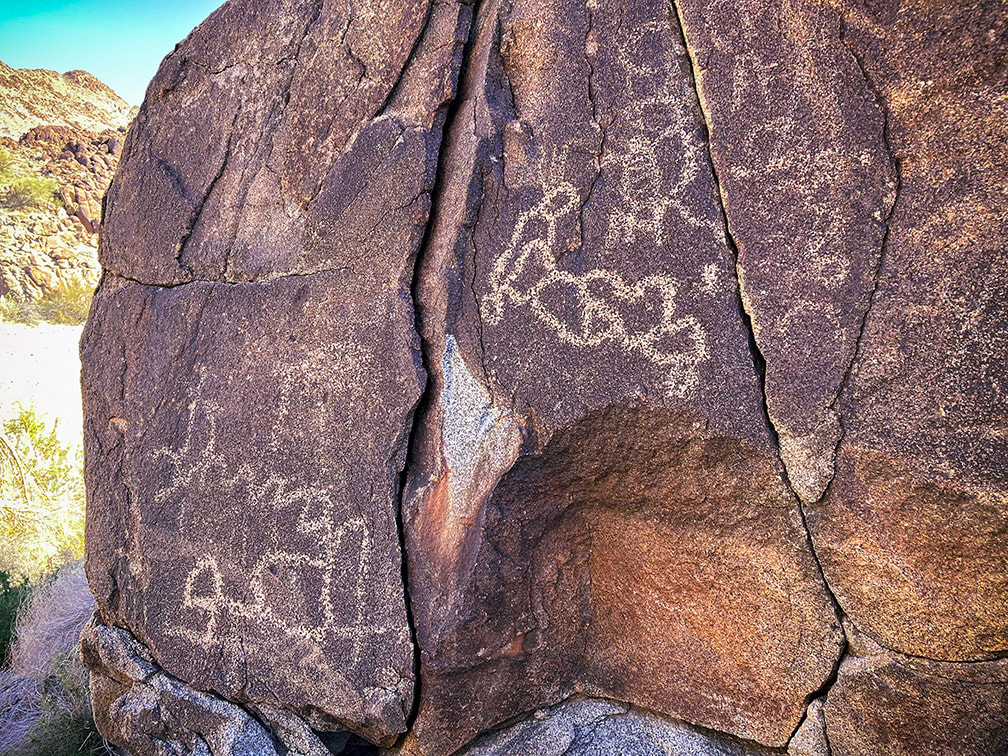

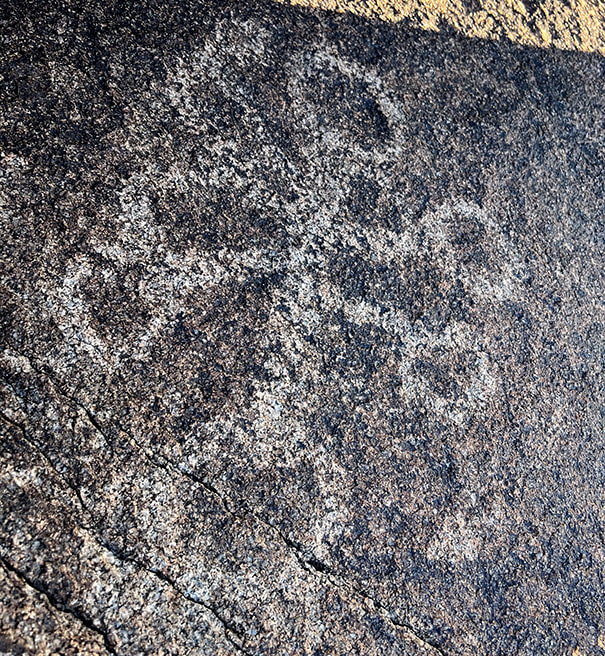

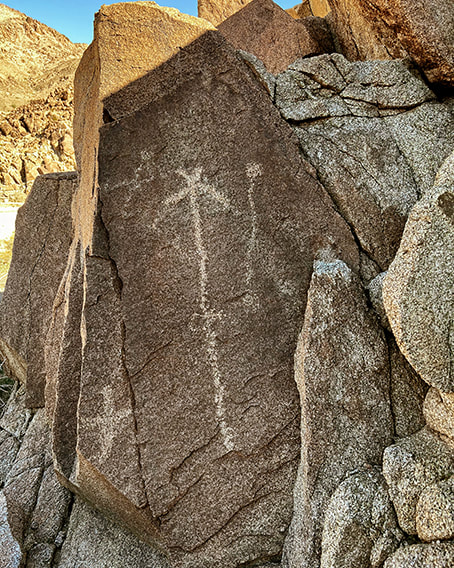

One of the best petroglyph sites in the Colorado Desert, Corn Springs has rock art dating back 10,000 years and was a major water stop by traveling Chemehuevi, Cahuilla, and Yuma Native Americans. Vision quests may have occurred here. Related: Trip Stats Location: Colorado Desert section of the Sonoran Desert - Southern California, Chuckwalla Mountains, Corn Springs Wash. What: Bureau of Land Management Corn Springs Campground, at a California palm oasis that was a major occupation site for prehistoric Native Americans. Petroglyphs are on east and west side of the wash. BLM information and interpretive trail guide. Driving: Graded gravel road 10 miles south of CA interstate 10, near Desert Center, east of Joshua Tree NP south entrance (link for driving directions in BLM site above). Coordinates: 33.626046, -115.324935. Geology: The Corn Springs Wash is a strike/slip (transverse) fault, as are many other faults in southern California, including the nearby San Andreas Fault. The petroglyphs are carved into granitic rocks that include dikes of felsic (light-colored rocks), and mafic (dark-colored rocks) that cross-cut them (see photos below). Corn Springs Site scientific inventory: Clewlow, C. Rock Art at CA-RIV-981: Chronology, Imagery, and Function Great Comments on this Post If it wasn't for a petroglyph enthusiast who commented on my post In Search of the Rattlesnake Petroglyph, I might not have known about the fantastic Corn Springs rock art. He gave me good tips about where to find extraordinary petroglyphs and suggested I read the book, A Field Guide to Rock Art Symbols of the Greater Southwest, by Alex Patterson. I'm sure glad he contacted me; it's great to find someone who shares the same passion, curiosity, and appreciation of petroglyphs and the Native Americans' way of life. James Ponder also contacted me with links to two awesome feature articles he wrote for Inland Empire Magazine: -Aztlán in Our Backyard: The Southern California Origins of a Vanished Empire. (May 2023, p. 54). -Touring Coyote Hole: A look at Efforts to Preserve Ancestral Lands and Sacred Spaces in the California Desert. (January 2023, p. 62). He loves the Corn Springs site and writes about the work of the Native American Land Conservancy. Check out his Aztlán article - he reveals a concept that I hadn't heard of before - that the Aztec culture birthplace was near Desert Center (30 mins drive from Corn Springs site) and Blythe in California. He introduces Alfredo Acosta Figueroa's book, Ancient Footprints of the Colorado River: La Cuna de Aztlán, one that I'm planning to read. (His comments at end of this post). Fred and I were headed down to our annual Palm Springs, California visit anyway, so we added it to our agenda. Corn Springs is a 1.5-hour drive from Palm Springs, east on I-10, past the entrance to Joshua Tree National Park, near the Salton Sea, and well worth the trip if you are interested in American southwest history. Corn Springs was a reliable water source for Chemehuevi, Cahuilla, and Yuma Native Americans traveling between the Colorado River to the east and coastal areas and the Coachella Valley. Petroglyphs date as far back as 10,000 years, according to the BLM. This ancient trail has been traced to the Mule Mountains near Blythe, California. Steamboat Influences A noteworthy petroglyph appears to be a river paddle-wheel steamboat. My post reader suggested I try to find this petroglyph and sent me an interesting report, "Steamboats on the Colorado River, 1852 - 1916" by Richard E. Lingenfelter. Uncle Sam, a small steam tug was the first of many vessels to run the Colorado River, transporting miners, soldiers, ranchers, and merchants and their tools, supplies and millions of dollars of gold and silver extracted from mines. Native Americans, such as the Yuma and Mojave, depended on Colorado River resources witnessed the invasion of the Gold Rush of 1849. This steam boat mode of transportation caused the change and suppression of these ancient river peoples. Interestingly, the Yumas operated their own ferry at Yuma Crossing. Extensive steam boat travel on the Colorado and its tributaries ceased when the Southern Pacific Railroad completed tracks to Yuma in 1877, providing faster and cheaper shipping of goods. But river commerce still held on after that with the introduction of gas-powered boats and gold dredges. All river trade was finally ended with the damming of the Colorado River. Petroglyph of what may be a Colorado River paddle-wheel steamboat (left) and a drawing of the Explorer on the Colorado River in 1858 (right), from Steamboats of the Colorado River: 1852 - 1916. Vision Quests and Ringing Rocks In my quest to learn more about the Corn Springs petroglyphs, one article or research paper led to another and then another and soon I found myself reading about shamans, hallucinogens, and trance states. Sort of like falling down the Google Scholar rabbit hole. I hadn't intended on writing about suppositions that these petroglyphs are a result of vision quests and that one rock might have been used for acoustics, but it's too interesting and fun to pass up. Unlike Utah rock art with its many representational human- and animal-like forms, Corn Springs petroglyphs are geometric and abstract shapes and patterns that some rock art researchers believe are illustrations of trance-state mental imagery. The realm of neuroscience more formally defines these patterns as "entoptic" (within vision) and phosphenes, which some say is the universal language of the human brain throughout all cultures, since our nervous system has remained the same through human history. Entoptic images are visual effects that originate within the visual processing system anywhere between the eyes and the brain cortex. Certain symbols are common throughout locations all over the world. There seem to be quite a few entoptic images etched in these boulders. Rituals using dance, music, chanting and psychoactive substances to induce trance states where ancestors were visited and wisdom was enhanced may have occurred at Corn Springs. Visions and images were then recorded in the rock etchings. Grid, parallel lines, dots, zigzag lines, nested curves, and filigrees (thin meandering lines) are the six common forms seen in Upper Paleolithic art as a result of drug-induced visions, according to some researchers. Some say that a shaman would act as an intermediary between mortals and the supernatural by gathering power through the spiritual world. I attempted to correlate some of the petroglyphs in my images below to information I found in my search. But we can't assume that we know for sure what the intent was of the people who engraved these petroglyphs. We can only speculate. Some of these symbols may have been made to create communication for a good food harvest or for fertility. These ancient symbols were here long before the advent of formal language (for an interesting book on human relationship to the natural world and language, check out The Spell of the Sensuous: Perception and Language in a More-than-Human World by David Abram). Common entoptic forms as a result of drug-induced visions as recognized by contemporary researchers. from Altered States: The Origin of Art in Entoptic Phenomena by Eric Pettifor (who adapted from Lewis-Williams and Dowson). The curvy petroglyph upper left resembles a filigree form (examples on third row of first column in chart above) as does the large petroglyph bottom right that seems to radiate from a central point. A large flat rock, supported by small rocks, protruding from a small recess in the massive granitic outcrop on the west side of Corn Springs Wash amidst the biggest concentration of rock art is said to be a "ringing rock." A horizontal line of pecked marks extends across the top of this rock. "Ringing rocks," when struck with a small hammer-stone produce metallic, ringing, or gong-like sounds. Not much research has been done to understand exactly why some rocks are "ringers." One explanation is that clay minerals on the surface of the rock weather and cause a molecular-level change in the crust, which then increases new internal stresses. I need to go back to Corn Springs to see if that rock will ring, and while I'm there, climb the high summits in the Chuckwallas. The supposed "ringing rock" is the flat, slanted gray rock in the right of this photo. Probably a pegmatite dike cutting through granite. One source said that some petroglyphs seem to relate to these dikes. Fault (seismic) activity influences the water table and hence the availability of water for California fan palm trees. The infamous San Andreas Fault, a horizontally-moving fault where North American and Pacific tectonic plates meet extends just southwest of the Chuckwalla mountains. This desert has two personalities: peaceful, quiet and sedate, while at the same time unstable, waiting for its earth to move and shake things up. The Chuckwalla Mountains have an interesting gold mining history from the late 1800's, and in a separate hike in adjacent Orocopia Mountains (Spanish translation: "lots of gold"), Fred and I found what looked like an old miner's dwelling at the top of a long wash (see below), now called "Hotel California." Corn Springs was so named because early white visitors found feral corn plants grown by Native Americans, who at times were able to use the springs for growing food during years when water was abundant. The Love of Deserts: Liberation and Peace Nearby Chuckwalla Mountain and Black Butte, accessed by the historic Bradshaw Trail (now the Bradshaw Trail National Backcountry Byway), are two summits we added to our "to do" list. William Bradshaw built this trail in 1862, the first route across Riverside County, California to the Colorado River; it was used to transport miners to Arizona. "The love of mountains is best," a quote included in my Quotes on Nature page, was inscribed in Greek on one of the Swiss Alps summits in 1558. Perhaps I will inscribe "the love of deserts is best." on a lonely and bare desert summit someday. Corn Springs is a place to find solitude, and recharge if you need breathing space and respite from cities, televisions and smart phones. The desert allows you this: calm (usually), liberation, perspective and peace. "In sublimity - the superlative degree of beauty - what land can equal the desert with its wide plains, grim mountains, and its expanding canopy of sky!" - John C. Van Dyke, The Desert Huge tamarisk tree at Corn Springs. Dot images are one of the six common entoptic forms produced when in a trance or during vision quest. Some researchers claim dots indicate corn kernels, stars or rain. The top figure with horizontal line (sky line) and the six lines descending from (rain) it is thought to be a rain symbol. The slanted lattice is considered to be a basic entoptic (within vision) design. The horizontal line with parallel vertical lines under it (lower left) may represent rain. Beautiful dike cutting through granite. Some cool stuff at the site. Chuckwalla lizards have the ability to inflate their lungs to wedge themselves into rock cracks as a defense mechanism against predators, like the red-tailed hawks and coyotes. Native Americans used sticks made from the ironwood trees for retrieving chuckwallas from the cracks. The stick had a spear and hook, so the chuckwalla would be stabbed to deflate the lungs, and then would be pulled out of the crack using the hook. Fall colors of an ocotillo (Fouquieria splendens) preparing to go dormant for the winter. Yellow and red leaves are caused by a wet summer followed by a slow autumn drying period. Ocotillo in Orocopia Mountains. The orange and yellow leaves seem to occur when there is more late-season rain than usual. California fan palms (Washingtonia filifera) at Corn Springs. Ocotillos on Orocopia Mountains, a range west of the Chuckwalla Mountains. "Hotel California" is inscribed on a plaque nailed to this rock house. "Hotel California", located up long wash in the Orocopia Mountains near Joshua Tree National Park's southern entrance. References

Carter, L. 2021. Ancient rock art and psychedelics.., The language that connects us all. From website: www.roXiva.com. Corn Springs - Wikipedia. Crowell, J., et al. 1979. Tectonics of the Juncture Between the San Andreas Fault System and the Salton Trough, Southeastern California. Dept. of Geological Sciences, University of California - Santa Barbara. Devereux, P. 2008. The Association of Prehistoric Rock Art and Rock Selection with Acoustically Significant Landscape Locations. The Archaeology of Semiotics and the Social Order of Things. BAR International Series #1833. Freers, S. 2018. Simply Scratching the Surface: Petroglyph Chronology in the Colorado Desert. San Diego Rock Art Association. Rock Art Papers, Vol. 19. Gough, G. Sacred Landscape and Native American Rock Art. Lingenfelter, R. 1978. Steamboats on the Colorado River: 1852 - 1916. The University of Arizona Press. Powell, R. 1981. Geologic map of the crystalline basement complex in the southern half of the eastern Transverse Ranges, Southern California: Supplement 1 from "Geology of the Crystalline Basement Complex, Eastern Transverse Ranges, Southern California: Constraints on Regional Tectonic Interpretation". Ringing Rocks and Sonorous Stones. 2020. From website Spooky Geology. https://spookygeology.com/ringing-rocks-and-sonorous-stones/

We celebrated another Christmas with a sublime, scree-filled desert summit challenge and a Tecopa Hot Springs soak afterward.

Ascending wash to walk between the black hills to the right and the two small hills just to the left of Fred.

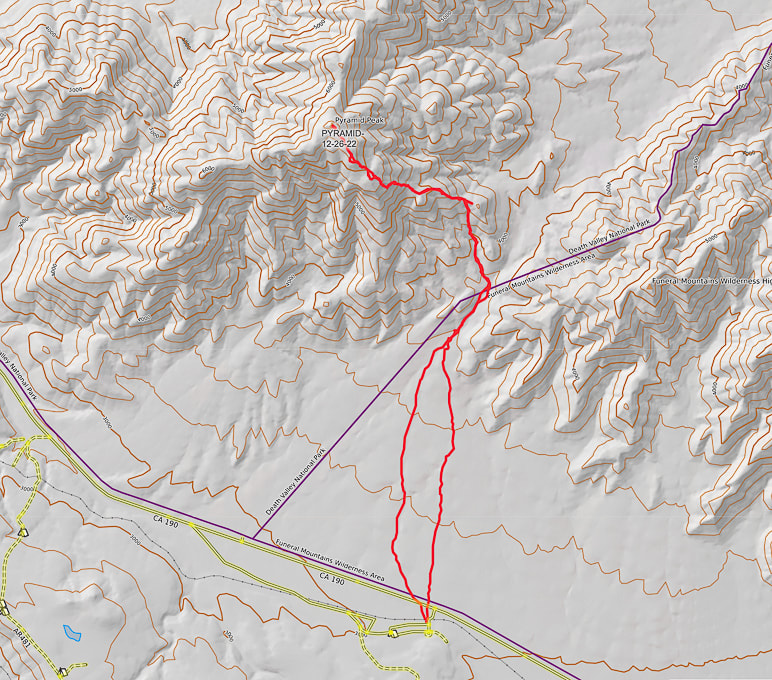

Pyramid Peak is black and white - on horizon. Death Valley got its name from a wagon party trapped in the valley in the 1849 California gold rush. One man perished in this hottest place on Earth. One of the travelers was said to have proclaimed, "Goodbye, Death Valley" as they traveled west over the mountains.

Trip Stats for Standard Route (Southeast Ridge)

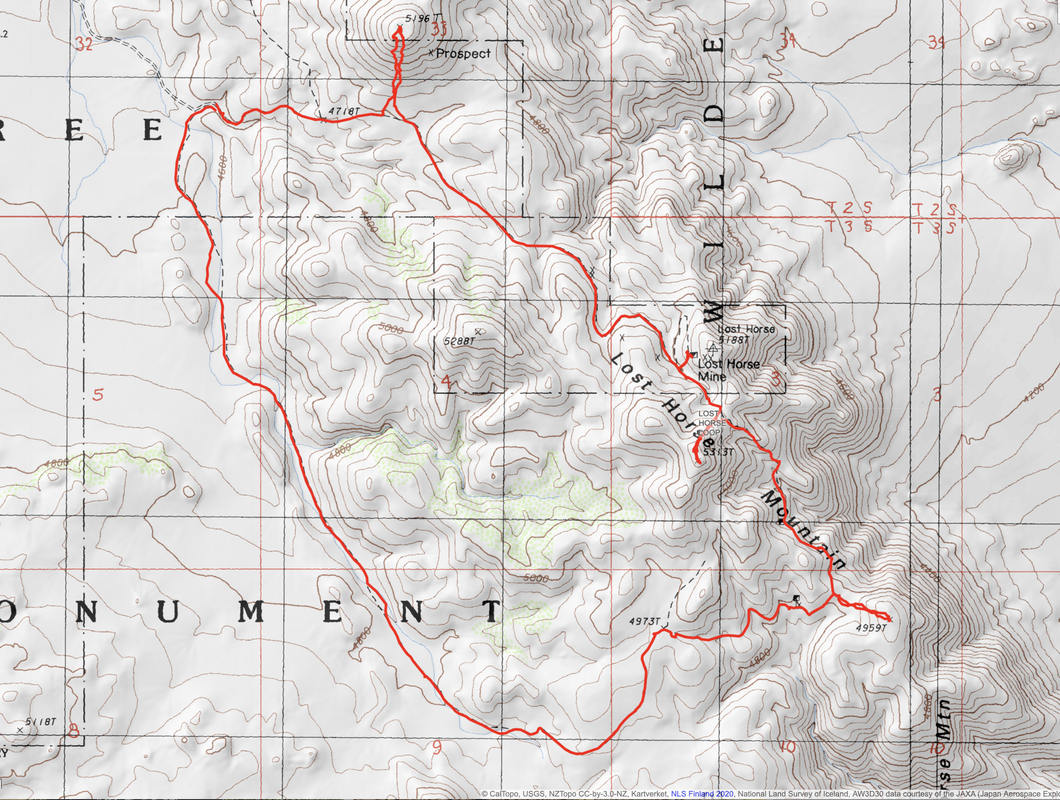

Location: Amargosa Range, Funeral Mountains high point, Eastern Death Valley National Park. Distance/Elevation Gain: 10.4 miles out and back/3,700'. Trailhead = 3,041'. Summit = 6,703'. Difficulty: moderate - strenuous effort Class 1-2: most time is spent on three major rock/scree slopes. Mostly discernible trail with rock cairns; occasionally requires focus as it becomes faint. Prominence: 3,703'. Coordinates: Trailhead at Hwy 190 = 36.34048, -116.59866. Summit = 36.39196, -116.61228. Maps and Apps: Topo Maps US app, StavIsLost route map, Garmin GPS. Date Hiked: 12/26/22 Directions to trailhead: Park on Highway 190 at an old RV/campground with Pyramid Peak in view. If coming from Death Valley Junction (east), drive ~ 11 miles. If coming from Furnace Creek in the park, drive 17-18 miles. Geology: The ridge hike is a journey through Ordovician-age (450 m.y.a.), heavily faulted limestone and dolomite (Ely Springs dolomite and Pogonip group carbonates). Pyramid Peak summit is Eureka quartzite and Ely Springs dolomite.

Overview

The words "Death Valley" may conjure up images of doom and foreboding, but it's really a land of mystique and fascination, and of extremes. In winter, it's one of the warmest places in the country, making it one of my favorite places to explore. You wouldn't want to be there in the summer, unless you want to experience an average July temperature of 116 degrees. It has the record for the hottest temperature ever recorded on Earth — 134 degrees. Last December, we hiked remote Pahrump Point with spectacular views of Death Valley's Telescope Peak on a cold and windy day, and warmed up in Tecopa Hot Springs Resort's hot springs. This year we "elevated" our summit challenge to hike the lonesome and talus-riddled slopes of Pyramid Peak in the Funeral Mountains, eastern Death Valley National Park. It's listed on the Sierra Club's Desert Peaks section, hence the discernible trail. I break this hike into four parts: a long alluvial fan/wash approach, followed by three steep, loose-rock slopes. Forbidding, massive dark grey limestone greets you at the top of the second loose-rock slope. Pyramid's summit is not in sight until you get up this face and walk around it to the left, where you see more talus slopes under big black spires. From its small quartzite perch, the summit affords a huge view of Death Valley's Panamint range capped by Telescope Peak, and into Nevada. Stunning views surround you the entire ridge climb. Sublime, raw, layered, folded, vast and lonely - the quintessential Mojave Desert.

Our Hike

What more could we ask for? The opportunity, legs and strength to summit a Death Valley peak, the views to remember forever, a natural hot springs soak, and one of the best steak dinners ever - all in the middle of the quiet Mojave.

We're living the dream! Keep on Exploring - it's good for the body, mind and soul!

Healthy creosote bush and lots of hedgehog cactus clumps on the way up this alluvial fan.

Almost at the small hills on the left - the approach continues along the base of these for 2.8 miles from trailhead where it turns NNW into a wide drainage/fan.

At the end of initial alluvial fan climb - taking a left around base of this hill to see large drainage.

Turning left into a major drainage with black rocks at the end of it - then the climb begins!

Finding a trail at the end of the wash that stays on the right side of the drainage to the left.

Trail heads up to the saddle above, with a good amount of loose rock.

Fred making his way up steep and loose rock to saddle (Talus slope #1).

Looking down the first talus slope to the wide wash we had turned into from approach alluvial fan.

Done with the first talus slope! Time for a break - looking back at the highway and valley we have just come up.

There's a few cairns to mark this first slope; afterwards, the trail is mostly discernible.

Looking ahead to the crazy, rugged mess of rocks we will ascend - glad there is a cairned trail! Pyramid summit behind the ridge. Go straight up the ridge in middle of photo, then bypass the brown-colored scree slope by hiking to its left, up through minor gully (center of photo). Reach the top of this brown rock to ascend the dark grey rock.

Continuing on less-steep portion of southeast ridge in between the steep talus slopes.

Getting through a minor limestone outcrop and looking at the fan we hiked up; walking under the two small hills at the upper left.

Look at that lovely scree field! Trail goes to the left of this, through a small gulley and manageable talus slope, through pink, deep red and yellow rocks.

Getting up and over this sharp limestone, where it flattens out somewhat.

View south from ridge.

This is "Talus slope 2" - photo is taken on the way down. This is on the left of the very steep scree slope.

Upper part of "Talus slope 2". This photo is taken on our way down.

Forbidding sight after topping off on ridge after the second steep talus slope. You can see the trail running in the middle of this, leading to the top of the left prominence, then skirts around it to the left, where you will see Pyramid Peak summit.

Looking back from the black rock ascent to the saddle we just came over and brief flat area.

Working our way up the black rock.

View of Pyramid Peak as trail traverses under left side of ridge walls.

Climbing "Talus slope 3" near the base of the summit.

Trail along left side of ridge near the summit.

Looking back to approach valley and the black "knife" ridge we had passed under.

The beautiful Eureka Quartzite on the summit of Pyramid Peak.

At Pyramid Peak's summit looking toward the east - Amargosa Desert.

Pyramid's summit!

Pyramid's summit looking down on our alluvial fan approach and Highway 190.

From the summit looking east toward the Amargosa Desert and Nevada.

"Amargosa" is the Spanish word for "bitter", describing water in the Amargosa River, which courses through Amargosa Desert.

On the summit looking toward Furnace Creek wash and Artist's Pallette in Death Valley.

View west of the Panamint Range and Telescope Peak, the highest summit in Death Valley at 11,043'.

The summit of Pahrump Point provides a closer view of Telescope.

Some cool stuff on the trail.

Celebratory rib-eye, beer and wine at Steaks and Beer in Tecopa, California - highly recommended for carnivores!!

That night after the hike, we walked into Steaks and Beer for our delicious ribeye and cherries jubilee.

Tecopa Hot Springs Resort - Tecopa, CA.

Early morning at Tecopa Hot Springs Resort's bath house.

Our tracks on the ridge portion of the hike to Pyramid Peak. Leaving major wash (lower left) to walk to the end of side wash to begin ridge climb.

Our GPS tracks from parking at old campground on California Highway 190 to summit of Pyramid Peak (CalTopo maps).

Click on map for larger image

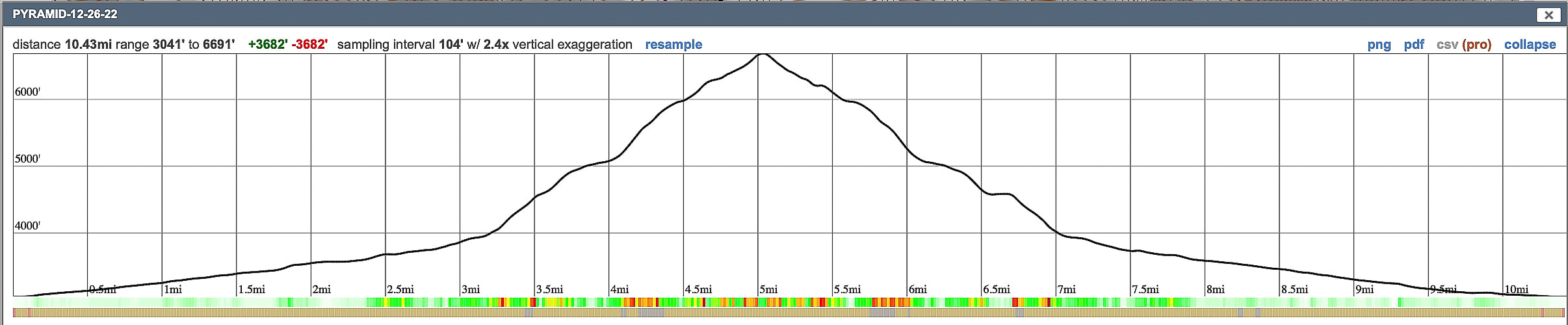

Elevation profile for out-and-back hike gaining 3,700' in 5.2 miles. Hike up alluvial fan/wash for the first three miles.

References

Fridrich, C.J., et al. Preliminary Geologic Map of the Southern Funeral Mountains and Adjacent Ground-Water Discharge Sites, Inyo County, California, and Nye County, Nevada. Geologic Formations. NPS - Death Valley website. McAllister, J. 2009. Geologic Maps and Sections of a Strip from Pyramid Peak to the Southeast End of the Funeral Mountains, Ryan Quadrangle, California

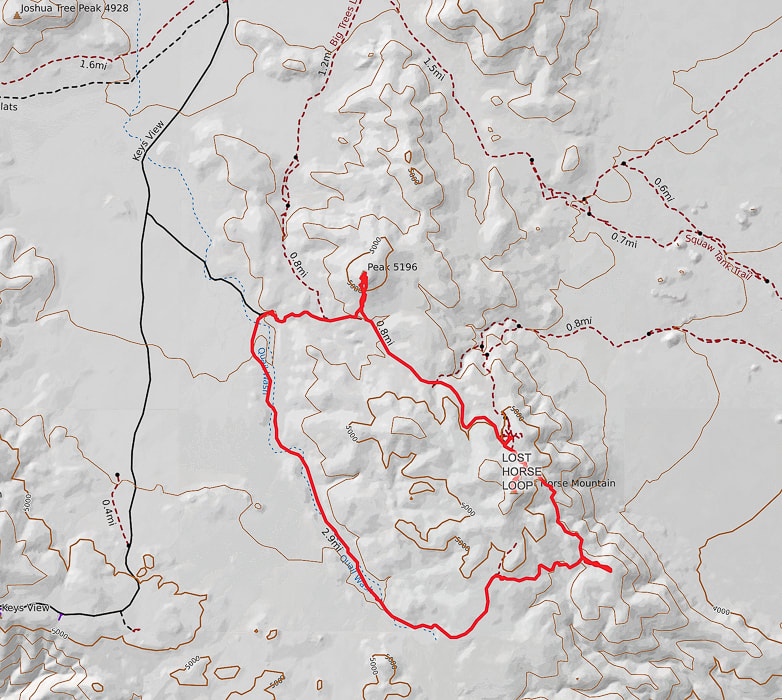

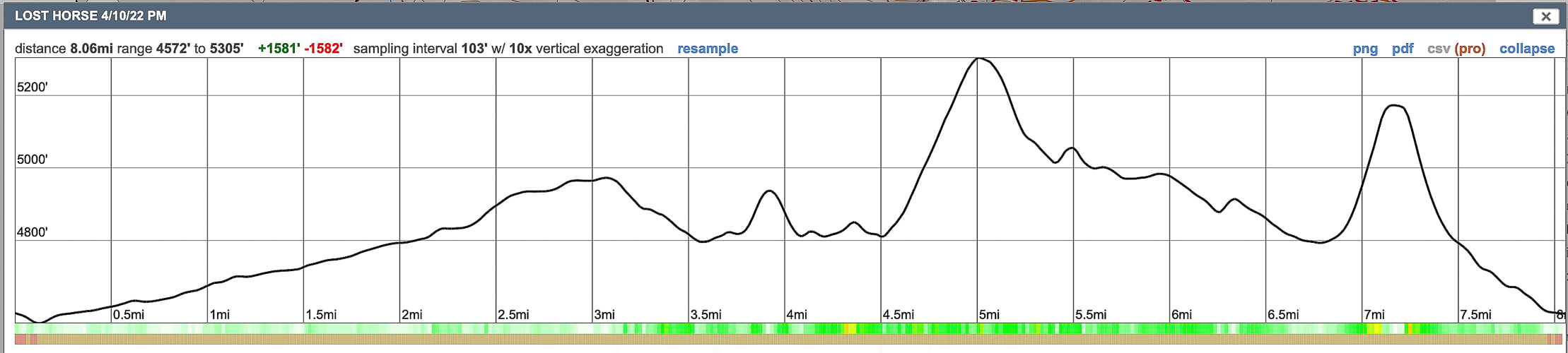

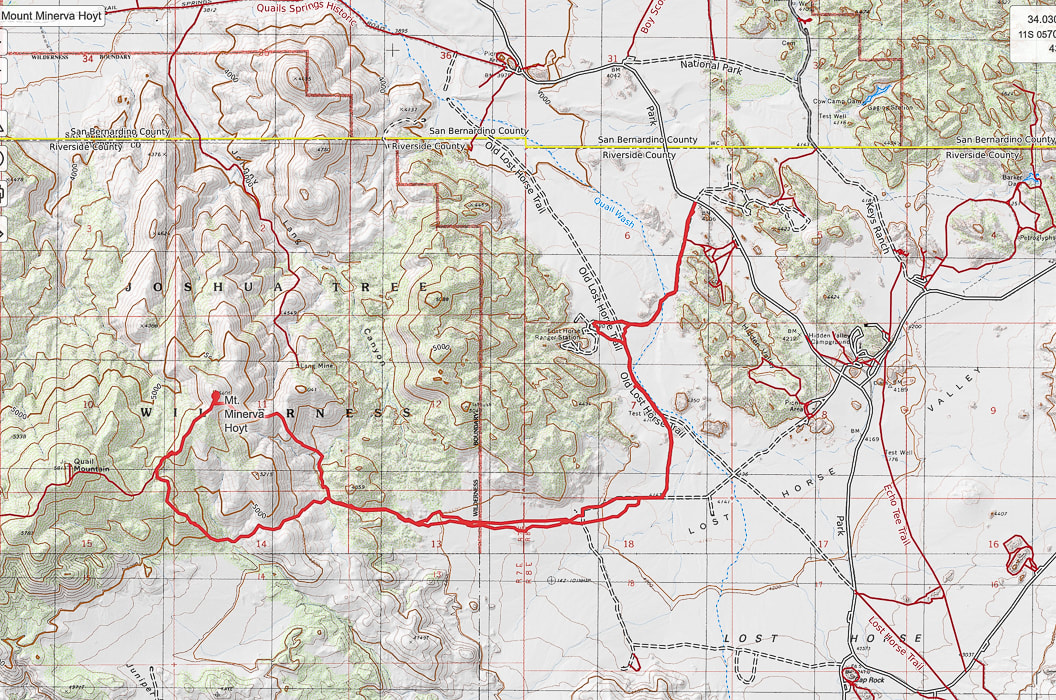

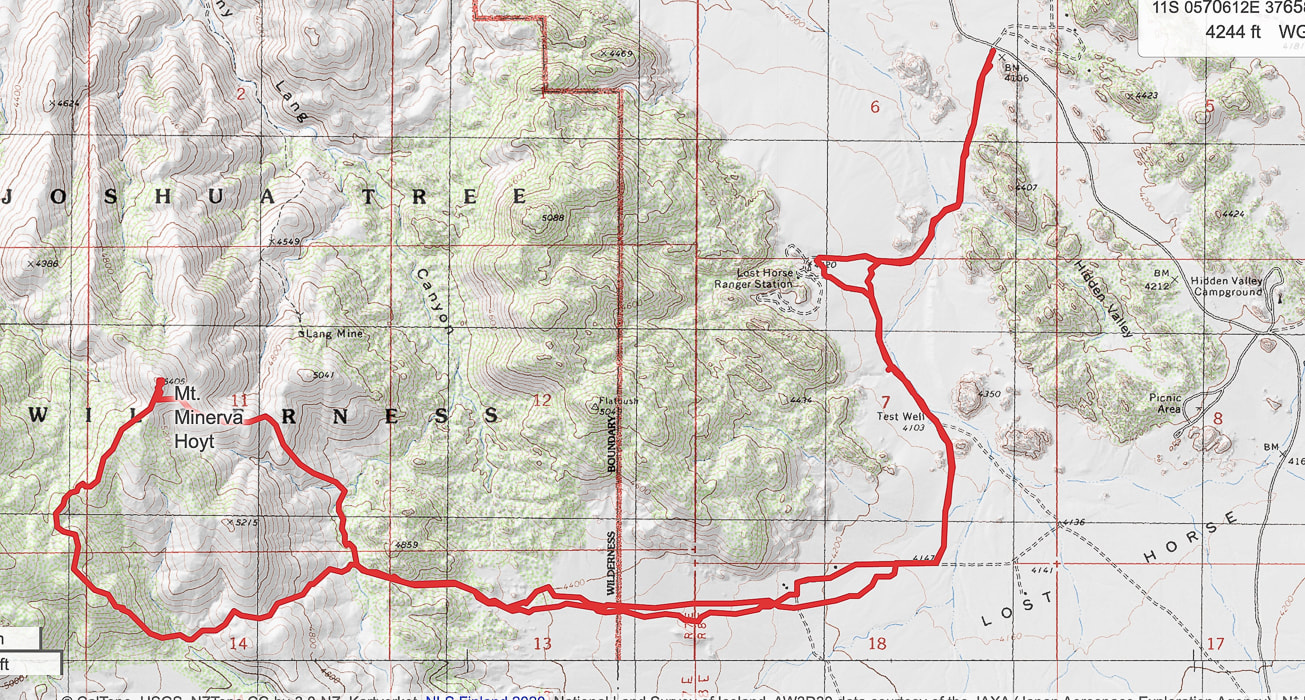

Hike three high points and view the historic Lost Horse Mine along this western Joshua Tree NP trail.

Starting in Quail Wash.

Trip Stats

Overview: Make the Lost Horse Loop hike even more interesting by bagging a few peaks along its route to get a feeling of the vastness of Joshua Tree NP and wilderness, with views of San Jacinto Peak in Palm Springs. Check out the plaque that commemorates Lost Horse Mine stamp mill, one of the best-preserved of its kind in our national park system. Coordinates: Lost Horse Mountain = 33°.56'13.74" N 116°.08'10.01" W.

Navigational aids: Trails Illustrated Joshua Tree National Park #226 map.

Date Hiked: 4/10/22 Geology: The Lost Horse Loop trail and mine is located in granitic quartz biotite gneiss (metamorphic) related to Pinto gneiss age 1.7 billion years ago - some of the oldest rocks in California. Biotite is dark mica mineral. The Lost Horse Mountains are one of only three occurrences of basalt in Joshua Tree NP.

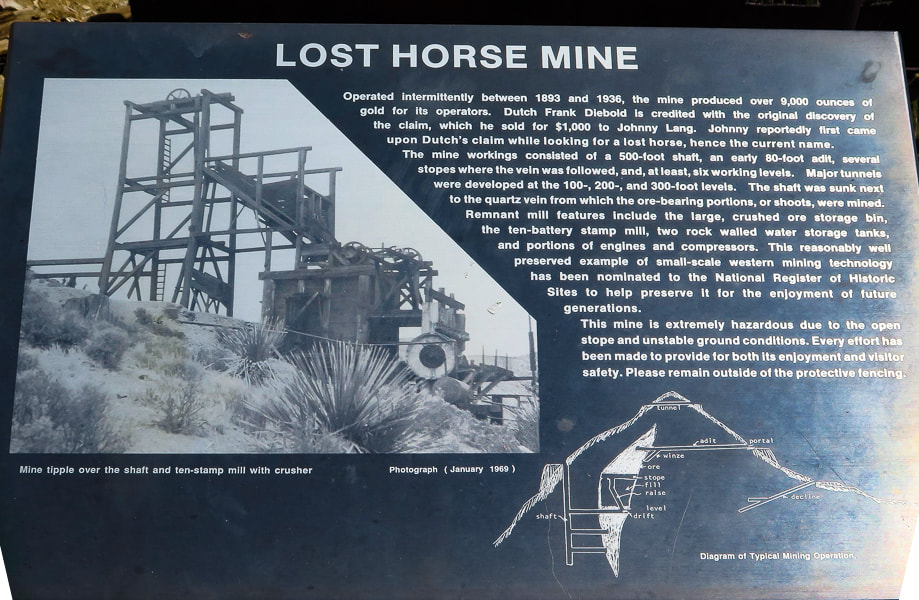

Cattle rustlers and Gold Mining in Lost Horse Valley

If you were a cattle rustler in the 1870's southwest, you would look for a remote and hidden area with enough water and good stands of trees and plenty of native grasses and other vegetation to feed your "stock". A place where the nearest law enforcement officials were at least 50 miles away. For the McHaney brothers, this place turned out to be the higher, western side of what is now Joshua Tree National Park, in Lost Horse Valley and Hidden Valley. Bill McHaney's gang took cattle from Mexico and Arizona to hide them in other Joshua Tree valleys as well, then returned stolen horses. Johnny Lang also drove cattle into Lost Horse Valley after his brother was gunned down in New Mexico. He woke up one morning to find his horse gone. He tracked it to the McHaney's place but was told to leave the area. Luckily, Lang met "Dutch" Frank who had discovered a mining claim, but was afraid to set up mining operations because he was also being hassled by the McHaney gang. Lang bought the rights to the mine and called it "Lost Horse", after enlisting three partners to protect the claim against claim jumpers in 1893. The Lost Horse Mine ultimately produced 10,500 ounces of gold and 16,000 ounces of silver. Today, the Lost Horse Mine stamp mill is considered one of the best preserved in a National Park service unit. We hiked three high points along this loop. The most interesting summit was Peak 5196 because of the columnar basalt at the top. In a land dominated by granite, this is one of only three occurrences of basalt. From its summit, just northeast of the trailhead, are extensive views of Queen Valley to the east and Lost Horse Valley to the west. A few days before, we had hiked Mt. Minerva Hoyt, named after the woman instrumental in President Franklin Roosevelt's proclamation to designate Joshua Tree National Monument.

Sign at trailhead. We hiked the trail counter-clockwise.

Our Hike in the Mojave

As the road to Lost Horse Trail climbs to around 4,000 feet elevation in the western, Mojave desert section of Joshua Tree NP, the amount of Joshua trees, junipers and yuccas is more prevalent compared to lower, dryer Sonoran desert Pinto Basin to the east at 1,700 feet. Although it's a moderately-used trail, you get the feeling of remoteness surrounded by mountain ranges. The trail circles Lost Horse Mountain, trekking through Quail Wash and over juniper and shrub-covered hills darkly punctuated by scattered gneiss boulders.

By the time we got back to the trailhead parking lot, it was full. Another fun day in Joshua Tree's Mojave desert. The three extra summits were the "icing on the cake" - worth the effort.

Time and Space in the Desert

Joshua Tree is an awe-inspiring land shaped by Earth's events spanning the Proterozoic alteration of pre-existing rocks into gneiss, to the five Proterozoic through Cretaceous intrusions of plutons that produced gold and silver and its famous sculpted rocks, to the relatively recent faulting that uplifted mountains and blocked canyons. A landscape that has a tumultuous origin, but a relaxing presence. Dark and rubbly mountains spring out of flat, buff - colored valleys. A slight haze of dust still hangs in the air after last night's wind storm. I stand looking over it all - breathing space. Back straightens, chest raises, diaphragm brings in creosote and sand-scented air. To some, this expanse and space feels intimidating; to me it feels comfortable. To some it looks formidable with its hot, dry stillness and sharp- spined cacti; but I admire their motivation to survive under the hot, penetrating sun. To walk in browns and buffs for awhile and then suddenly come upon magenta and bright yellow cactus blooms is cause for celebration. I remember liking these ragged and gangly Joshua trees and contrasting smooth, rounded boulders the first time I saw them 38 years ago. I revel in the sublime space and quiet that calms my mind. Grateful for the feeling of being connected to this land.

"Time and space. In the desert there is space. Space is the twin sister of time. If we have open space then we have open time to breathe, to dream, to dare, to play, to pray to move freely, so freely, in a world our minds have forgotten but our bodies remember. We remember why we love the desert; it is our tactile response to light, to silence, and to stillness."

- Terry Tempest Williams

Never Stop Exploring!

From summit of Point 4959, looking at Malapai Hill.

Beautiful 1.7 billion-year old gneiss - and hedgehog (?) cactus.

Circling around Lost Horse Mountain (on far horizon) to hike up its northeast ridge.

Remains of a very sturdy fire place and bed frame.

Our first summit - Point 4959.

Three types of rock: great example of gneissic banding - a textural lineation of minerals in metamorphic rock created by pressure and intense heat (foreground). Malapai Hill in middle of valley created by magma. Valley rock is monzogranite.

Looking at Lost Horse Mountain from the slopes of Point 4959. You can see Lost Horse Trail as it climbs to the saddle on its northeast ridge. Hike that ridge to the summit.

Some cool stuff on the trail.

Summit of Lost Horse Mountain

From Lost Horse Mountain's ridge: a view of Lost Horse Mine.

Lost Horse Mine stamp mill through chain-link fence.

Walking up to Point 5196.

Beavertail cactus just before the blooms.

Columnar basalt on Point 5196.

References

California Geology. 1998. Department of Conservation, Division of Mines and Geology. Dilsaver, L.M. 2015. Joshua Tree National Park: A History of Preserving the Desert. Prepared for National Park Service, Joshua Tree National Park, Twentynine Palms. Joshua Tree Geology Tour Road. Joshua Tree National Park Geology - Rock Types. Digital-Desert: Mojave Desert. Trent, D.D. Geology and History of MInes, Joshua Tree National Park.

Named after the woman who lead conservation efforts for what is now Joshua Tree National Park, Mount Minerva Hoyt looks over wide, sandy valleys of Joshua trees and piles of weathered granite boulders, famous for their climbing routes.

Trip Stats

Overview: To honor the woman behind Joshua Tree NP's conservation campaign, hike to her namesake summit. Bag nearby Quail Mountain, Joshua Tree's highest summit, for a tour of two peaks and great views on top of Joshua Tree. Experience all of the famed attributes: Joshua tree groves, rock climbers scaling eroded granite, a glimpse of the private historic Randolph Ranch, a beautiful wildflower-filled canyon and an enjoyable ridge walk. Location: Joshua Tree National Park/Wilderness - North Entrance Station out of Joshua Tree, Southern California. Distance/Elevation gain: 12 miles out and back. Trailhead = 4,061', Summit = 5,405'. Net gain = 1,700'. Coordinates: Parking = 34.02926 N -116.17905 W. Summit = 34.01347 N -116.22694 W. Difficulty: Moderate Class 1-2 Fees/Permit: $30 entrance fee, good for 7 days. Navigational aids: AllTrails map, Trails Illustrated Joshua Tree National Park #226. Date Hiked: 4/9/2022. Geology: Begin in the eroded boulder piles of monzogranite, a deep intrusive igneous rock uplifted and eroded to create large depths of coarse rock-fill in the valleys. Monzogranites are a biotite (mica) granite that are the final crystallized product of magma, after other minerals have solidified (like olivine). Mount Minerva Hoyt summit is made of orthogneiss, a metamorphic igneous rock. Interesting to note that the summit of nearby Quail Mountain is not made of this gneiss, but instead made up of monzogranite. Good explanation of magma crystallization.

"This desert with its elusive beauty. . . possessed me and I constantly wished I might find some way to preserve its natural beauty."

- Minerva Hamilton Hoyt

Hike Summary

There's a few ways to hike to Mount Minerva Hoyt and nearby Quail Mountain, Joshua Tree NP's highest. Both are listed on Sierra Club's Hundred Peaks Section. Years ago, Roger and Maria Keezer led us up Quail Mountain from the west. This time Fred, Scott and I approached from the east, parking at a lot on Park Drive, ~ one mile south of the Boy Scout Trailhead reached from Joshua Tree's west entrance. You could also begin the hike from the Hidden Valley Nature Trail parking. The weather was perfect - sunny and warm. Scott met us for the hike, as he has for many over the years. We have recently hiked Monument Mountain and Pinto Mountain in Joshua Tree together, and Pahrump Point near Death Valley. Hiking Directions

Joshua Tree NP's area is 795,000 acres, slightly bigger than the state of Rhode Island. Thankfully, almost 430,000 acres of it is wilderness, so there is a lot of space to roam and discover. If you want solitude, you can quickly get away from popular spots. If you want to climb to get a view, there are six mountain ranges. Pay attention to maps and apps, because you can easily get disoriented in this huge desert. By getting out there, smelling, touching, and seeing the life of the Mojave, you will gain a sense of wonder and admiration for the species that survive there.

The land in Joshua Tree has had a varied and interesting history, from the Pinto Culture, its initial transitory hunter-gatherer inhabitants to the miners and ranchers that arrived in the 1800's, to people seeking wellness from tuberculosis, and today's recreational visitors. The year 2021 saw the first time that park visitors totaled more than three million. Minerva Hoyt created a desert conservation exhibit for the Garden Club of America show in New York in 1928 that also appeared in London, England. Her magnificent exhibits not only stressed the beauty of these American deserts, but also the fragility and potential dangers. The widespread attention her exhibits brought influenced many southern California residents to decorate their own gardens with transplanted cacti. Vegetation was taken from the natural desert gardens in the pass entering Palm Springs, California, easily accessible to those traveling on the major highway between that city and Los Angeles. Commercial florists added to this theft. The same occurred in the Mojave desert, where small Joshua trees were uprooted and planted in yards, and larger Joshua trees were harvested for their wood. Joshua trees were set ablaze so that people could signal to each other. Today, it's hard to believe this destruction actually occurred, because we have learned to respect these beautiful deserts - appreciation has grown significantly. It took this destruction to motivate Minerva Hoyt into action to preserve this awesome park. When I lived and worked in the Palm Springs area in the 1990's, I was fortunate to be a volunteer to survey desert tortoises along with my hiking friends. We worked with the Joshua Tree National Monument's biologist, walking through the Pinto Basin, a vast sublime open desert. Upon coming across a tortoise, we weighed it, counted its scutes, measured it and glued an identification tag onto its shell, so it could be tracked. This was the beginning of my fascination for desert ecology, and of great memories that we friends still recall today.

Keep Exploring our Deserts!

Starting off on road that leaves from parking area off Park Boulevard near Hidden Valley. This road leads to an intersection with a trail that leads 0.5 miles to the Hidden Valley picnic area, another place to start this hike.

Our GPS tracks leading from Park Boulevard to a loop ascending Mount Minerva Hoyt.

Continuing west along Old Lost Horse Trail

Old Randolph Ranch - go around fenced property. I could not find much on the history of this ranch. It appears the owner had a sense of humor (see photo below).

Randolph Ranch - "May it Never Crumble".

Randolph Ranch, a private inholding in Joshua Tree NP.

Hiking west up Lost Horse Valley past Randolph Ranch. Mount Minerva Hoyt is dark-covered peak on the right.

Some cool stuff on the trail.

Long-nosed leopard lizard

Gambelia wislizenii

The end of Lost Horse Valley funnels you into a small canyon or draw with visible path leading to saddle where you then descend into wash at base of Mt. Minerva Hoyt and Quail Mountain.

Arriving at the saddle before the drop into the wash at base of mountains. We climbed this ridge westward toward Quail Mountain and then headed northeast on the cross country trail between Quail and Minerva Hoyt to hike Mt. Minerva's southwest ridge to the summit (point on horizon to the right).

Dropping 200' down into wash after saddle. Mount MInerva Hoyt on the right horizon. On the way up, we ascended the ridge in front of us in this photo; we descended Minerva Hoyt's east ridge seen on horizon to end up in this wash.

View of Mt. San Jacinto (overlooking Palm Springs), still covered with a lot of snow.

Walking up ridge toward Quail Mountain after getting out of wash.

Looks like a trail marker on the ridge up. Looking back at the saddle we crossed over to get into wash below.

Scott on ridge trail.

Hiking on cross-country trail that connects Quail Mountain to Mt. Minerva Hoyt. Summit on the left - there is a guy standing up there!

The last 200' climb to the summit is easy, punctuated with beautiful metamorphic boulders and cactus gardens, plus a spectacular view of the desert that Minerva Hoyt fought so hard to protect.

Fred and Scott signing summit register.

One of the beautiful "cactus gardens" on the summit.

One of the biggest prickly pears (may be a dollarjoint prickly pear) I have seen! The saddle that we ascended is just above Scott's head and slightly to the right under the two rock summits - aiming for that landmark on our way back!

Claret cup hedgehog

Echinocereus triglochidiatus

Minerva Hoyt's east ridge path - headed toward wash below.

Getting near wash and saddle, our entry point into Lost Horse Valley.

On the way back.

Our GPS tracks

Click for larger map

Elevation profile

References

Earle, S. Crystallization of Magma from Physical Geology. BC Campus. Minerva Hoyt. National Park Service. 2015. Dilsaver, L.M. 2015. Joshua Tree National Park: A History of Preserving the Desert. Prepared for National Park Service, Joshua Tree National Park, Twentynine Palms.

Another rugged summit from the Sierra Club Desert Peaks Section's list completed! On this narrow perch above desert valleys thousands of feet below, we saw spectacular views of Nevada and southeastern California and experienced "flow" - the secret to happiness.

Scott on Pahrump Point's southeast ridge just under the summit.

Trip Stats

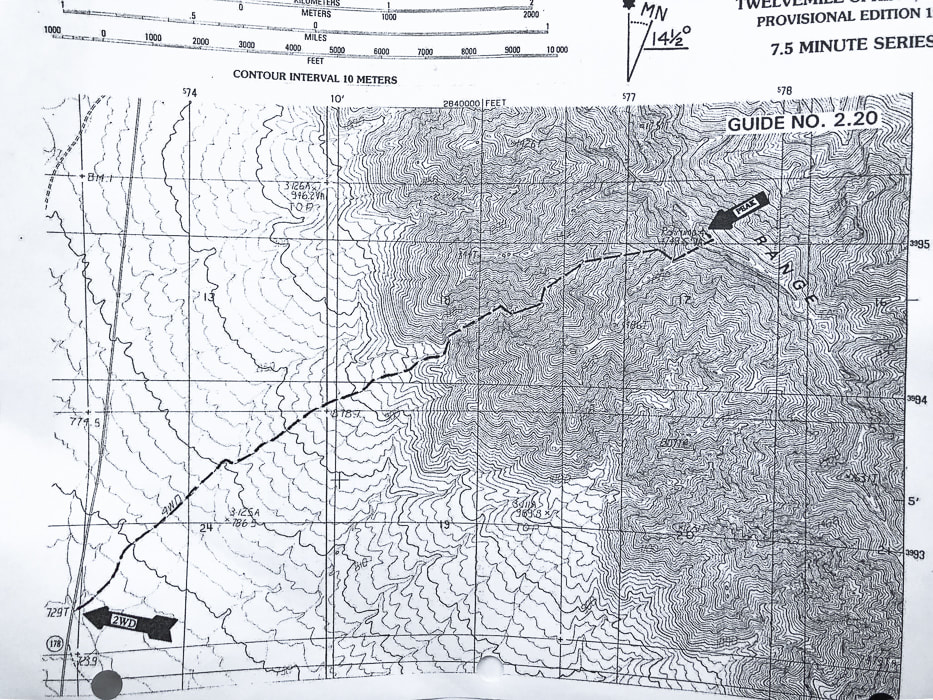

Overview: This classic Mojave desert hike begins on an alluvial fan, ascends through boulders up an ever-narrowing canyon, switchbacks up a talus slope to emerge onto Pahrump Point's southwest ridge for a huge view of the summit's steep walls. From here, the route winds up a gully and treks through a few "passages" in its steep face to gain its narrow summit ridge crest. See fossils and plenty of rough limestone, as well as fantastic views of Telescope Peak in Death Valley, Mt. Charleston near Las Vegas, and the town of Pahrump. Attention to hike directions and navigation crucial to finding correct route. Location: Pahrump Point is in the remote Nopah Range Wilderness Area is just over the California/Nevada border, east of Death Valley National Park. Its rough and rocky summit rises above Pahrump, Nevada. Distance/Elevation Gain: 7.6 miles roundtrip from CA Hwy. 178 trailhead to summit; less distance if you can drive in further on gravel road leading to canyon. Elevation gain from highway = 3,400'. We began hike at 2,600'. Summit is 5,410'. Difficulty: Strenuous Class 2+ with occasional use of hand for balance. Lat/Long: Trailhead at Hwy 178: (UTM) 11S 0573213E 3992648 N. Summit: 0577422E 3995282N. Navigational aids: AllTrails map with GPS tracks, Sierra Club Desert Peaks Section hike directions - Pahrump Point. Date Hiked: December 17, 2021. History: "Pahrump" is a derivation from the Southern Paiute Pah-Rimpi term meaning "Water Rock" describing the abundant natural artesian wells in the area.

Pahrump Point trailhead location.

Aprés Hike

One of the best things about this hike is the delightful hot spring pool we soaked our weary bodies in afterwards at Tecopa Hot Springs Resort. We met our friend Scott to camp there on a few unseasonably cold December days. This resort, just outside of Death Valley and near the Nevada/California border had been abandoned for 10 years before the current owner purchased it, and it still wears the characteristics of an old-time hot springs resort, with original buildings, nothing fancy here - very remote and bohemian, complete with a 40-foot labyrinth. With no cell service or internet, it was heaven for three days. One of its mission statements:

"We see ourselves as stewards of sacred land and ambassadors of goodwill."

The Southern Paiute tribe discovered these hot springs hundreds of years ago. One night, after a soak, we enjoyed live music on an outdoor stage, standing around a fire pit sending smoke up into a cold and starry desert sky. The next morning we had excellent huevos rancheros in Tecopa Hot Springs Resort Bistro.

Bath house with 2 hot springs pools at Tecopa Hot Springs Resort, California.

Our Hike

In the classic Mojave desert fashion, this rocky peak rises abruptly from the desert floor with dramatic, unobstructed views from a small, almost precarious perch at the summit. Pahrump Point looks difficult if not impossible from a distance, so it's fun to find the route through its steep cliff face. I'm glad Scott brought along the hike description from Desert Peaks Section manual. There are three crucial points along this route that you need to recognize in order to negotiate the rocky gullies, canyons and ridges to find most efficient way to the summit. The hike switches from Pahrump Point's southwest ridge to its southeast ridge where an easier route is present, just under the summit. Trip reports describe starting this hike just off of CA Highway 178 and the road leading to the mouth of the canyon, the distance of 1.8 miles. With our high-clearance truck, we drove just under one mile up this gravel road and parked to walk the rest of the way to its end at the mouth of the canyon framed on each side by alternating light-and dark colored Cambrian rock layers. A few cairns identify the trail throughout the completely rocky canyon bottom. A path initially goes along the toe of the left canyon wall, and then to the right, but most of the time is spent maneuvering through rocks and boulders in the canyon bottom. Once topping off on the southwest ridge after climbing a talus slope out of the canyon, the peak's cliffs come clearly into view, as well as a long and deep canyon to the south. To make the switch to the southeast ridge to summit, there are a few very important and prominent cairns for direction. The last few hundred feet climb to the summit is fun - you go by a hole in the rock that looks down into another steep canyon, then up a steep, short gulley. This empties you onto the final Class 2+ climb up Pahrump Point's manageable face, where you reach a fun and short summit ridge that is only slightly spooky. The narrow summit elevates you thousands of feet over desert playas, with a clear view of snow-covered Telescope Peak - the highest in Death Valley. The ridge to the next high point to the north seemed treacherous, so being content with our accomplishment, we basked in the nearly winter solstice sun. We occasionally cursed the loose rock on the return talus slope, after getting off the ridge. I wondered if age has caused me to be slower on this terrain. Picking our way through the boulders in the canyon, looking for cairns to give us a clue for a better route. Exiting the canyon onto the immense Chicago Valley, we turned back to see the Nopah Mountain range a fiery yellow/orange of sunset. Looking forward to dinner at the Crowbar Cafe and Saloon in Shoshone to celebrate another adventure - three friends who (still) like to hike together after all these years. It was great to hike once again with Scott, who said at the summit, "This is good for my soul!" Hiking to these amazing places with your friends and overcoming physical and mental obstacles together is good for your soul and can help you experience "flow" - the secret to happiness and optimal experience. The concept of "flow" is getting more attention lately and is the subject of my next post, as well as positive psychology, body movement science, enhancement of goal pursuit and well-being .

"Into the forest I go, to lose my mind and find my soul."

- John Muir

Initial approach through Chicago Valley up gravel road to mouth of canyon and then to Pahrump Point, just right of middle horizon. Cold and windy December morning in the Mojave.

End of road, trail goes up wash. Here, trail is seen on left side of canyon; it switches to the right side further up.

Initial main canyon walk alternates between canyon floor and side trails.

Trail seen on left side of canyon initially.

Coming down from a trail on the right side of the canyon, then up bottom of canyon to left and right fork; take right fork.

Tall cairn at 4,120' elevation that indicates to take the canyon to the right.

Trail then ascends up right side of canyon to 2 large cairns. From here, trail traverses slope and then drops you to the base of talus slope and ridge saddle.

Heading up canyon to the right at intersection with main canyon. This right fork takes you up talus slope to saddle at ridgeline.

Getting closer to the ridge

A look back toward Telescope Peak in Death Valley to the northwest.

On a moderately loose talus slope, getting closer to notch on ridge; then peak clearly seen to the left.

Large cairn marking saddle on ridge at top of scree slope. Peak is seen clearly at this point.

Once on ridge at 5,100 feet, see summit, and another 300-foot ascent to it; continue following ridge shortly to a ducked/cairned notch - head left through that notch to traverse to the left through another marked notch where there is a "window rock" on its left side. The route avoids the steep cliff face under the summit.

Cairn on left marks the traverse to the notch with "window rock".

Gully just after "window rock" which is on the left side of trail.

Out of short gully and now fun Class 2+ on final ascent.

Looking down canyon toward Chicago Valley to the south.

Entry up face of summit block on the summit's right side.

Reaching the summit ridge.

Southeast ridge just under the summit.

At the summit; trail goes through the snow on left side of this ridge in photo.

Scott and Fred on the summit of Pahrump Point - 5,410 feet!

Looking southeast down the Nopah range.

Mt. Charleston, north of Las Vegas, in background.

On Pahrump Point's summit.

A very organized peak register.

Trail on ridge - working our way back down.

"Window rock" on left side of trail is a landmark to navigate trail.

Ivory-spined agave

Some cool stuff on the trail.

(clockwise from top left) Hedgehog cactus, bryozoan fossil, ivory-spined agave, triangulation survey marker at Pahrump Point's summit.

Parting shot - sunset on Pahrump Point in the Nopah Range.

Celebratory dinner at the Crowbar Cafe and Saloon in Shoshone, a few miles from Tecopa Hot Springs, CA.

Sad to see these go - the limestone proved to be too rough for these worn KUHL pants.

Labyrinth at Tecopa Hot Springs Resort

Tecopa Hot Springs Resort

Tecopa Hot Springs Resort Bistro - the best huevos rancheros for breakfast!

Moonrise in Tecopa, California.

Seemoore's Ice Cream - "The World's Tallest Ice Cream Stand"

Pahrump, Nevada.

AllTrails GPS tracks from beginning of canyon (lower left) to Pahrump Point.

Route map from Sierra Club Desert Peaks Section

click for larger view

References

Wikipedia. Pahrump, Nevada. Jennings, C.W. 1958. Geologic Map of California Death Valley sheet. Why Does Experiencing 'Flow' Feel so Good? A Communication Scientist Explains. theconversation.com. Flow Theory: An Overview. sciencedirect.com. On Haystack, we found sun and solitude off of the Art Smith Trail in the Santa Rosa and San Jacinto Mountains National Monument, a spectacular view of Southern California's mountain ranges, and our old summit register entry from 2011. Related: First Cactus to Clouds Challenge - The Beginning of the Ultimate Desert Hike Pinto Mountain Hike - Joshua Tree Wilderness Desert Plants photos Monument Mountain Hike - Joshua Tree National Park In Memory of Roger Keezer Peninsular Bighorn Sheep near Art Smith Trail, Palm Desert, CA Ovis canadensis nelsoni Listed in 1998 as Endangered Species due to substantial population decline from disease, predation, habitat loss and human disturbance Cross - country to Haystack Trip Stats:

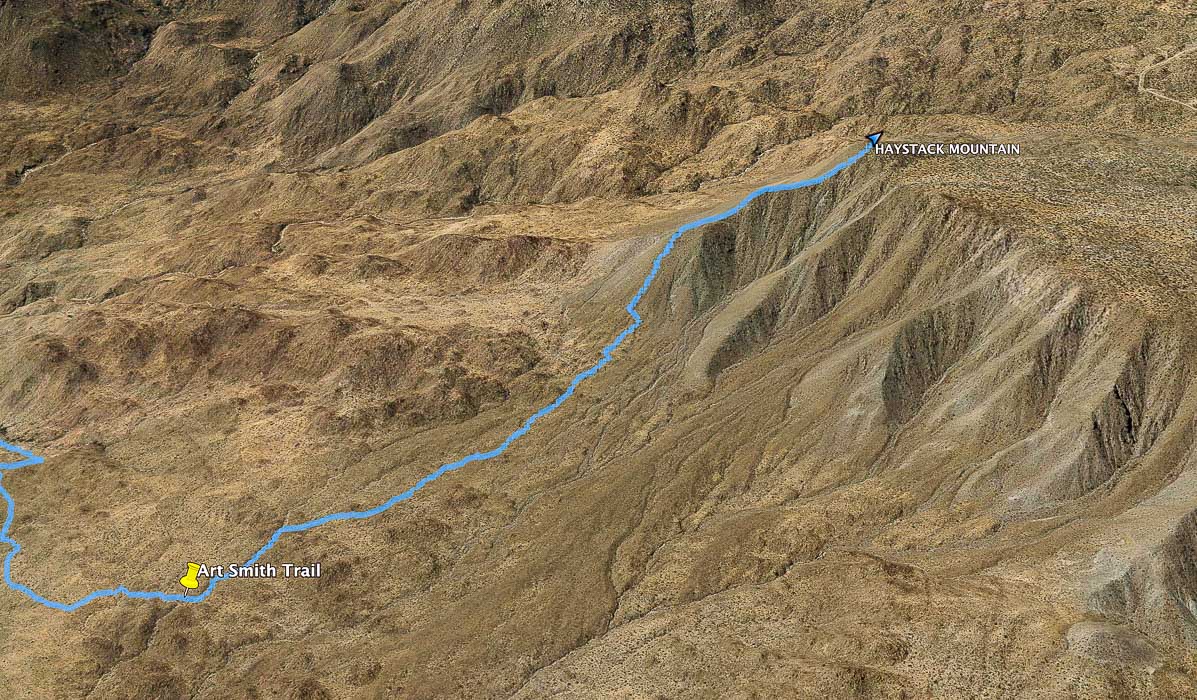

Directions to Art Smith Trailhead: Travel south on CA State Route 74 (Palms to Pines Scenic Highway) from CA State Route 111 in Palm Desert 3.5 miles to long sandy parking area on right of road just as it starts to curve to the left to ascend switchbacks up hills to the south. The Santa Rosa and San Jacinto Mountains National Monument Visitor Center is adjacent to parking, across SR 74. Hike Directions: (Topo map of our route below)

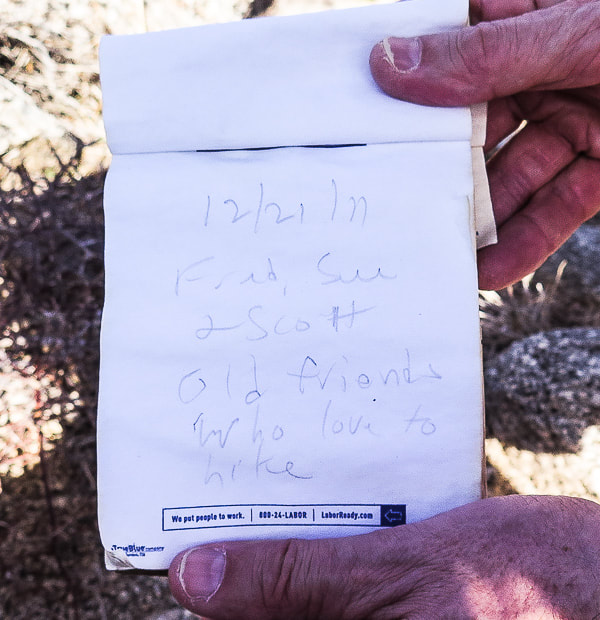

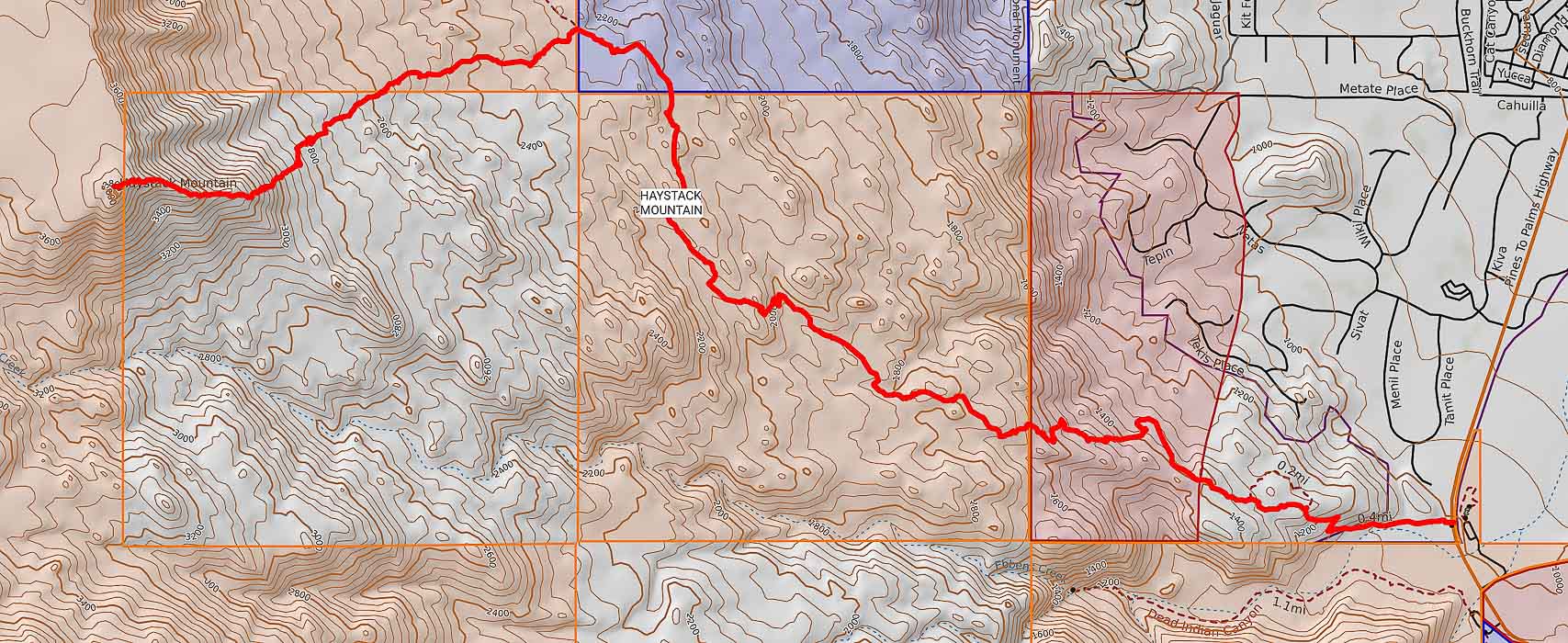

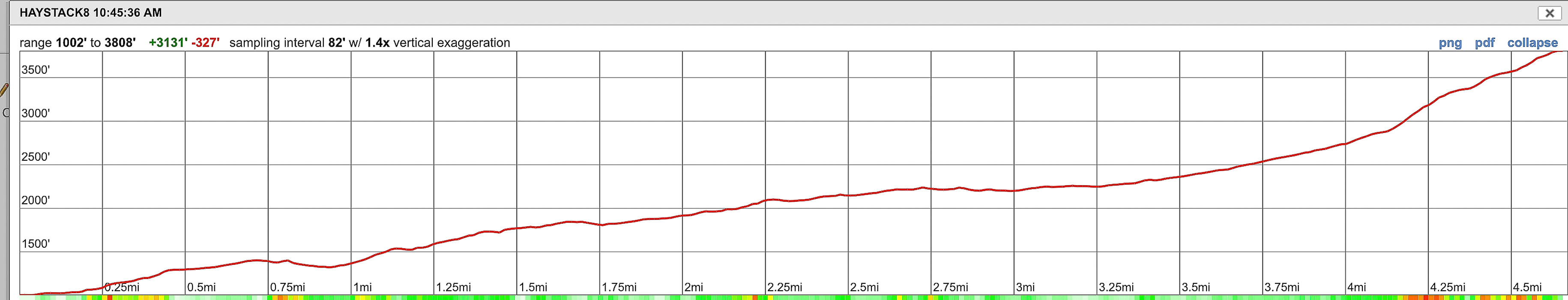

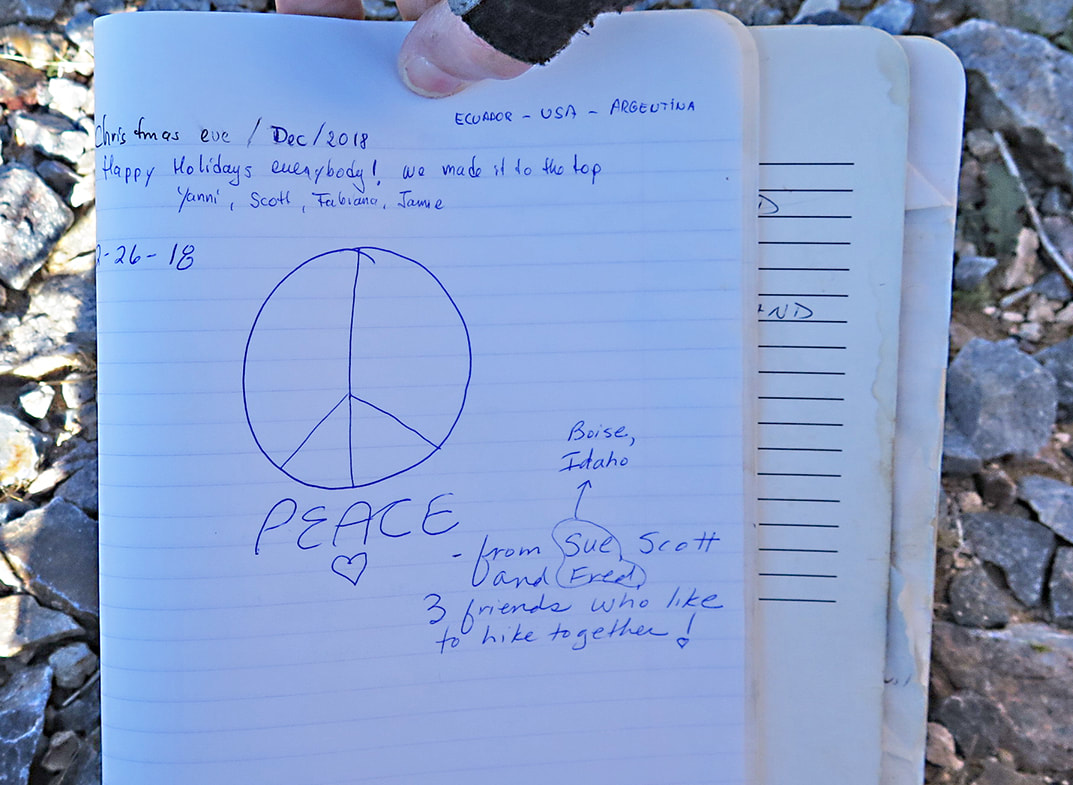

Cross-country route off of Art Smith Trail to summit of Haystack Mountain Yellow marker indicates point at which we left Art Smith and ascended wash Elevation at this point = 2,237 feet; ~1,600 feet to summit from turn-off Geology and History: The trail to Haystack Mountain treks through quartz diorite, a coarse-grained intrusive rock with 5-20% quartz (diorite has <5% quartz). It has the classic speckled black and white texture and large grain size. Quartz diorite is often confused with granite because they look similar. Both are intrusive rocks with a phaneritic texture in which mineral grains are visible without magnification. Granite, however contains 20-60% quartz. Quartz grains are not usually visible with quartz diorite, but can definitely be seen in a granite. This rock unit is Cretaceous age (144 to 65 mya). The efforts of Art Smith, a.k.a. "Trail Boss", a Desert Riders equestrian helped to establish the Desert Riders Trail Foundation, a non-profit trust for trail preservation and building. The Desert Riders equestrian club was initiated in 1931, has made 28 trails as of 2010, many of them follow ancient Cahuilla Indians' migratory hunting and gathering trails. "Probably I was too young and venturesome to feel dismay, but I know now what Mama must have felt as she looked out upon that savage scene of sand and rock and sky locked in the pitiless grip of desert summer." - Nina Paul Shumway, Your Desert and Mine, an account of her family's settlement and beginning of the date industry in the Coachella Valley. Our Hike The past few times we have hiked the Art Smith Trail, we have seen Peninsular bighorn sheep in Dead Indian Canyon near the rust-colored metal sign that marks the Art Smith trailhead, not far from the parking lot. They were listed as a federally endangered species in 1998. This morning, the sun shone brightly on the deep-walled Dead Indian Canyon and a group of ewes with their lambs. This trail, just west of Palm Desert, links to trails leading into the Indian Canyons in Palm Springs. The Coachella Valley is a special place for me and I carry memories of hiking all of its trails with dear friends that I will always keep in touch with. It's my "old stomping ground", or more aptly put, my old hiking ground. Living there in the 1980's and 1990's, we climbed, traversed, slid, sweat, laughed, got stuck with cactus spines, boulder-hopped, and celebrated our hikes and friendships. I am grateful I can still be able to hike these wonderful trails and when I do, all of the memories come back vividly. I met Fred on Mt. San Jacinto, and he automatically became a part of our hiking clan. Not many people venture off Art Smith to climb Haystack Mountain. To our surprise, we found the same notepad in which we had made our 2011 entry in the summit register can! I guess the dry climate and the sparse number of Haystack Mountain visitors helped preserve this small note pad. It's a simple message: "12/21/11 - Fred, Sue and Scott - old friends who love to hike." We missed Scott this year, but were looking forward to hiking with him to Pinto Mountain in the next few days. Walking on Art Smith Trail is a treat in itself, a meandering path with weathering rock piles, beavertail cactus and brittlebush blooming in the spring, and that satisfying crunch of gravel with each step. One can imagine Cahuilla Indians walking to water sources on the trail and equestrians from the Desert Riders on horseback winding through washes across the open desert. But to pick your own route cross country, dodging cholla cactus, sharp-toothed agave leaves and cat claw acacia shrubs, climbing up and sliding down boulders and dry waterfalls is the greatest satisfaction. Art Smith Trail was busy due to the Christmas holiday. This trail treks through a possible plutonic synform (a downward-closing or concave fold of topography). Shimmering green California fan palms pop up occasionally to the left of the trail, and the valley patchwork of forest green golf courses sprawl to your right. California fan palms Washingtonia filifera Haystack Mountain on the horizon as seen from near Art Smith Trail Leave trail at ~ 3.4 miles and hike to highest point at far left of long ridge Palm oasis in canyon on left We left Art Smith at 3.4 miles from the trailhead at a wide wash and headed west-southwest across relatively flat, open low desert. From here, it was 1.3 miles to the summit. We encountered no major rock barriers, only a few very small waterfalls and sandy benches covered with rounded boulders. I was surprised to see a few small junipers; the land is generously dotted with hedgehog cacti with their inch-long needle-spines. Wash ~ 3.4 miles in from Art Smith Trailhead at SR 74 in Palm Desert Climb up flank of cone to ridge - follow ridge to summit, seen in this photo Getting closer to the base - climb cone to ridge and follow to summit "False summit" on the ridge Hedgehog cactus (Echinocereus engelmannii) in foreground in front of cholla cactus Arriving at the base of Haystack, we gained its sunny east ridge by hiking straight up the steep flank to the left of the mountain, occasionally grasping rocks. The ridge is a Class 2 scramble with at least one "false peak" on the way up; not a long hike and the view at the summit is nothing short of spectacular. It is here you realize the enormity of this beautiful Colorado Desert and its mountain ranges. The controversial Dunn Road can be seen not far from the summit. It is a wide, sandy road that Mike Dunn carved out through the slopes of eastern Santa Rosa Mountains starting at Pinyon Flats in the 1960's and 70's. It traces around the contours of mountains, through what is now Santa Rosa and San Jacinto Mountains NM to Cathedral City. Because Dunn bulldozed some of his road on federal land, the BLM put a gate across the road. But Dunn would just bulldoze it down, and the BLM would fix it. I remember, when I lived in the Coachella Valley in the 1980's, Dunn Road was used for recreational jeep tours. Now of course since it is entirely on national monument land, it is only accessible to non-motorized travel. There were also differing opinions about whether Dunn Road compromised the bighorn sheep habitat. 360 - degree view from Haystack Mountain summit Summits include Mt. San Gorgonio, Mt. San Jacinto, Toro Peak, Martinez Mountain Also Little San Bernardino Mountains and southern Joshua Tree NP The summit view includes the highest points in the Santa Rosa Mountains: Martinez Mountain and Toro Peak, and also Mt. San Jacinto towering above Palm Springs. To the north lies Mt. San Gorgonio, the highest peak in Southern California, and the northeast the Little San Bernardino Mountains and the southern part of Joshua Tree National Monument. Ancient Lake Cahuilla filled the basin of the current Coachella Valley up until 500 years ago. This area is rich in culture and history - from the hunting/gathering Cahuilla Indians to the first settlers of this arid land, to the history of the date palm industry - not to mention the dramatic and substantial geologic history. The San Andreas Fault courses through the Coachella Valley. View from Haystack Mountain to the northwest Mt. San Jacinto (closer range) and Mt. San Gorgonio, the highest summit in Southern California (on horizon with snow) Our summit register entry from 12/21/2011: "Fred, Sue and Scott - Old friends who love to hike" Scott and Fred near Haystack Mountain summit - 12/2011 Palm Desert in background on valley floor, Southern Joshua Tree NP on horizon I recommend returning by the same route unless you are open for more adventure and willing to negotiate the steeper and rockier terrain to the southeast. We did just that but also ended up in a thick and tangled palm oasis, the palm fronds clashing in the breeze. Briefly crossing the oasis, crunching through dead fronds, we found our way out by ascending a steep canyon wall. Out into the open again, we saw not far from us two mountain bikers on the Art Smith Trail. Back to civilization. As we hike back along this very familiar trail, I picture a scene from 25 years ago - a faint image of a group of friends, walking in rhythm, boots crunching, happy voices laughing and talking, celebrating friendship and this great land. I bet we find both of our summit register entries the next time we summit Haystack. Desert agave The Cahuilla Indians roasted the heart of the agave in pits on rocky drainages Desert Fan Palm fronds Washingtonia filifera "Filifera" describes the white filaments between the segments of the frond Agave deserti Santa Rosa and San Jacinto Mountains National Monument Fred and Sue on the way down - another beautiful hike in the desert! Beginning of Art Smith at its intersection with California SR 74. Metal trail sign below. Wide wash is entry to Dead Indian Canyon Maps Topo map and our route and elevation profile to Haystack Mountain via Art Smith Trail and then traveling cross-country up east ridge Click on image for .jpg of topo map References:

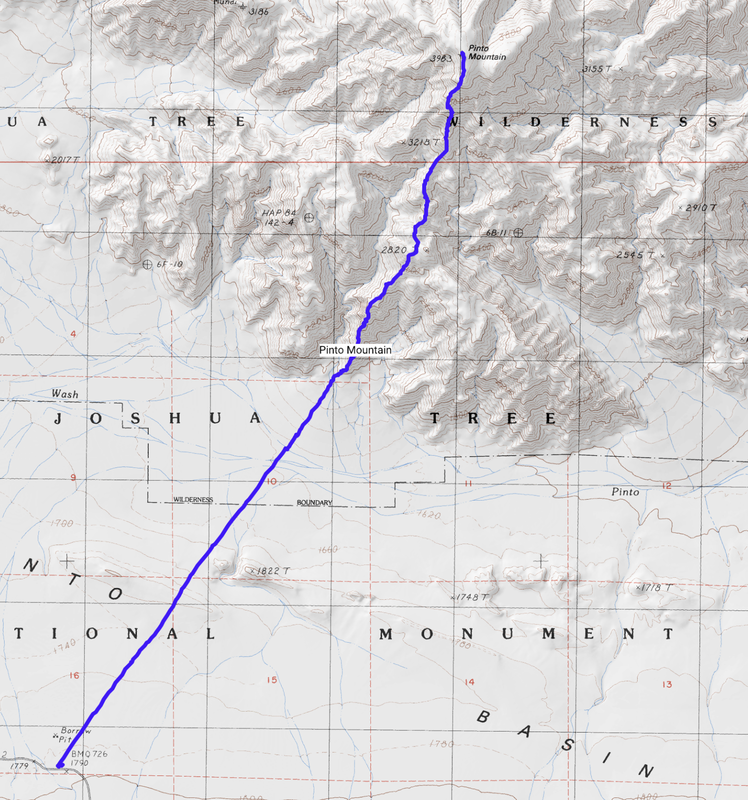

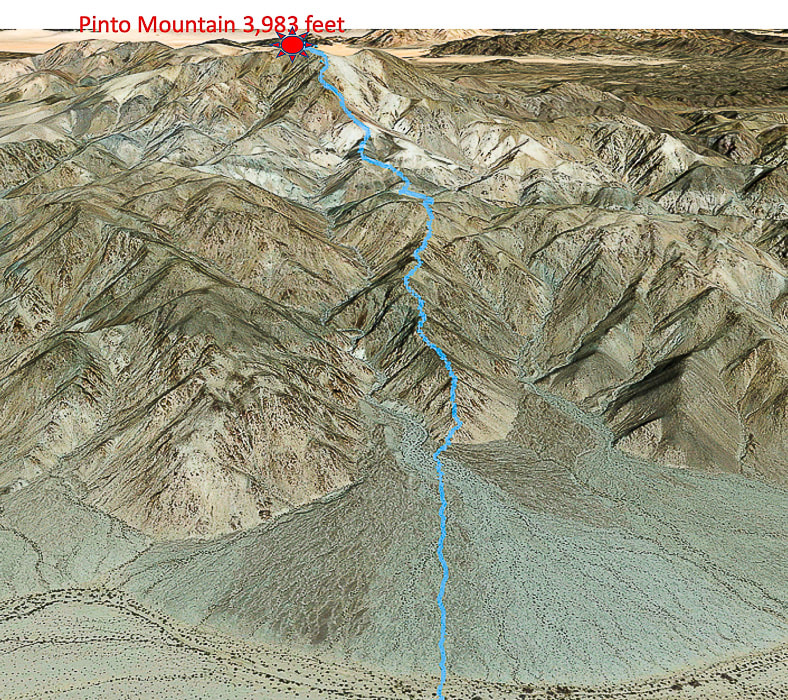

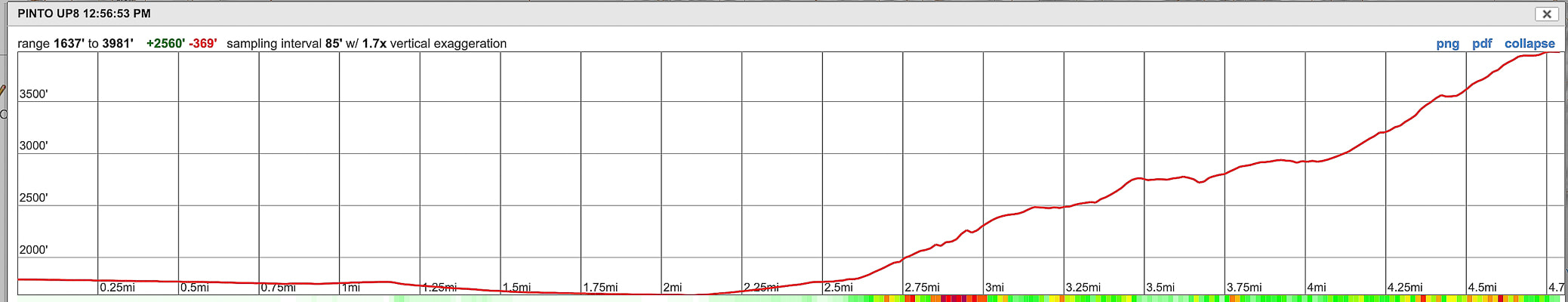

Bighorn Institute. 2019. Endangered Peninsular Bighorn Sheep. Retrieved from https://www.bighorninstitute.org/endangered-peninsular-bighorn Dibblee, T.W., and Minch, J.A., 2008 Geologic map of the Palm Desert and Coachella 15-minute quadrangles, Riverside County, California. Dibblee Geological Foundation. Patten, Carolyn. "The Desert Riders." Palm Springs Life, October 1, 2010. Desert Publications, Inc. Retrieved from https://www.palmspringslife.com/the-desert-riders/ Pearce, Al. "Dunn's Road Could be One of the Most Beautiful in Desert." Desert Sun, Volume 45, Number 214, 11 April 1972. In website: UCR Center for Bibliographical Studies and Research. Retrieved from https://cdnc.ucr.edu/cgi-bin/cdnc?a=d&d=DS19720411.2.59&e=-------en--20--1--txt-txIN--------1 Schumann, W. 1993. Handbook of Rocks, Minerals and Gemstones. Harper-Collins Publishers and Houghton Mifflin Company. Taylor, Joan. "The Dunn Road: A Checkered Past." Desert Report, 2007. Sierra Club publication. Winter, John D. 2010. Principles of Igneous and Metamorphic Petrology, 2nd Ed. Pearson Education, Inc., New Jersey. Our annual California desert peak hike with our friend Scott - this year to isolated and rugged Pinto Mountain in Joshua Tree Wilderness. Pinto Mountain - eastern Joshua Tree National Park in the Pinto Mountain Range Trip Stats Overview: The reward for the long walk across Pinto Basin followed by the rocky climb is the outstanding 360° views of the Mojave desert mountain ranges and the bright red barrel cacti that stand out in contrast. And, there's a sculpture on the summit! Distance: 4.8 miles to summit; round-trip 9.6 miles (out and back). Elevation Gain: Turkey Flats parking at 1,785 feet; Pinto Mountain at 3,983 feet = ~ 2,200 foot gain + regaining lost elevation = ~ 2,600 feet total. Maps: Trails Illustrated Joshua Tree National Park #226, USGS 7.5 min Quad Pinto Mountain. Entrance Fee Joshua Tree NP. Sierra Club Desert Peaks Section map of GPS tracks. Coordinates: Pinto Mountain summit: 33°57'12.23"N 115°48'10"W. Trailhead at Turkey Flats Backcountry Board: N33 54.109 W115 50.098. Difficulty: Easy across Pinto Basin; moderate to strenuous ridge climb - Class 1-2. CAUTION: Be prepared with GPS track and a good topo map - there is a lightly used trail on ridge but it's essential to have route-finding skills. Very hot/no shade mid-May through September. Date Hiked: 12/23/2018 Driving Directions From California I-10 East out of Indio, take Exit 168 into South Entrance of Joshua Tree National Park. Drive north 20 miles on Cottonwood Springs Road/Pinto Basin Road (past Joshua Tree Visitor Center) to Turkey Flats parking area and sign board on right side of road. Hike Directions

For the geocurious This hike treks through an array of different types of rock units ranging from Holocene cover (10,000 years ago to now) to Proterozoic Era (up to 2.5 billion years ago). A geologist's dream. It passes through some of California's oldest rocks; these rocks also top Monument Mountain, across Pinto Basin to the southwest.