|

The Fremont culture's expressions in volcanic rock, explosive geology, and a peaceful stay at Castle Rock Campground.

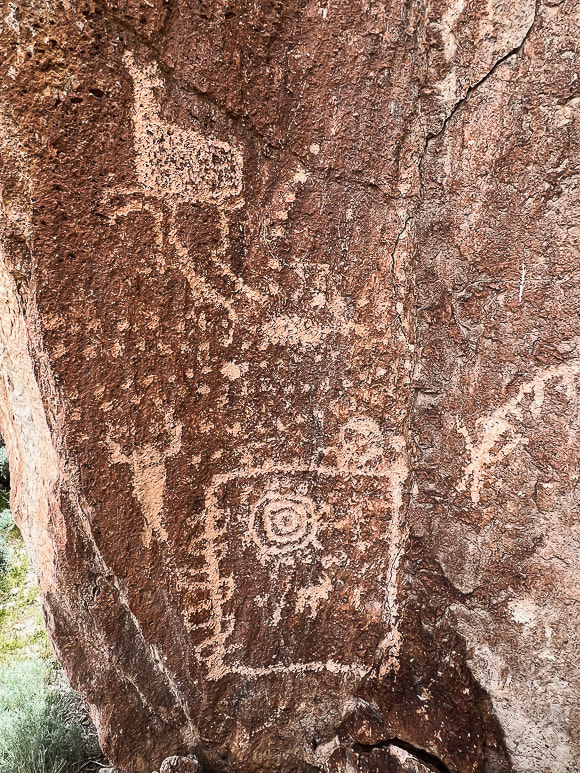

Fremont Indian State Park's Sheep Shelter, an alcove that uses a mirror to view its petroglyphs. Semi-circles and dots pecked on a line that extends the length of the alcove wall may have represented observations of the sky.

"Castles" at Castle Rock Campground weathering out of the Sevier River Formation that's made of sediments including ash, sandstones, siltstones, and lava flows.

Trip Stats

Overview: Massive volcanic ash ejections 19 million years ago provide the "canvas" on which the Fremont peoples carved numerous petroglyphs along Clear Creek Canyon, an ancient passageway between Utah's northern Pahvant range and the southern Tushar mountains. On the other side of Clear Creek, Castle Rock Campground's weathered sediment hoodoos make a unique backdrop to explore. Location: Central Utah - Fishlake National Forest - Tushar Mountains - Clear Creek Canyon along Interstate 70. Dates visited: May 27-30, 2023 Trails: most petroglyph sites involve short hikes on dirt/gravel. The Alma Christensen Nature Trail is a one-mile loop that hooks up to the petroglyph-viewing trails close to the museum. Google Map for Fremont Indian State Park and Castle Rock Campground: Closest town is Richfield, Utah. Exit 17 from Interstate 70 - take FR478: on south side is Castle Rock and on north side is Fremont Indian SP. Additional links: Fremont Indian State Park Brochure, Castle Rock Campground, Geologic History of Fremont Indian SP Books to Read:

- Kenneth Olsen Kohler

Related Posts:

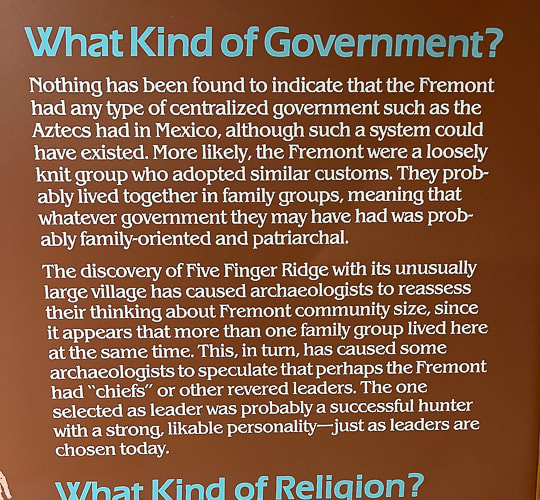

As mysterious as some of their rock art is, much of the ancient Fremont culture who lived in Utah ~ 300 - 1,300 A.D. also remains an enigma. Archaeologists use the word "Fremont" to refer to a "culture" or a "label," not a homogenous people because the Fremont territory included many ethnic groups and linguistic variation. "Fremont" is a generic term for people that lived in varied geographical locations, and had a diversity of lifestyles but seemed to have shared behavioral patterns such as subsistence. Some people were settled farmers; some were nomads that hunted and gathered; and some may have moved between these lifestyles. David B. Madsen, in his book Exploring the Fremont describes the Fremont lifestyle one of "variation and flexibility." They lived in natural rock shelters and pit houses dug into the ground, covered with brush roofs.

Four distinctive artifact classifications distinguish the Fremont from other prehistoric societies:

Since I love pottery (Fred says that our home can't fit any more pots!), I found an interesting Masters thesis, Fremont Ceramic Designs and their Implications by Katie K. Richards that was well worth the read if you are interested in the Fremont pottery and the evolution of research and archaeologists' changing philosophies about the Fremont throughout the decades since the late 1920's, when this culture was first identified along the Fremont River in south-central Utah. This article has a lot of great museum photos of Fremont pottery.

Fremont Indian State Park

I got the idea to visit Fremont Indian State Park after seeing it just off Interstate 70, coming back from the San Rafael Swell near Green River, Utah. I had read about this park in Geology Underfoot in Southern Utah, an informative book that features 33 "vignettes," three of which describe geology at Fremont Indian State Park and nearby Castle Rock Campground, where we stayed a few nights. Fred and I had already explored some of the places highlighted in this book, and I vowed to explore the rest of them, using it as a guide. Well, here's the first! I've seen petroglyphs carved into sandstone, basalt and granite, but not into tuff, a type of rock made of compacted ash as these are at Fremont Indian State Park, along Clear Creek. Why did the Fremont peoples carve so many petroglyphs along this Clear Creek Canyon corridor? Clear Creek provided ample water, and an old village with artifacts was uncovered during the excavations for building Interstate 70. This valley was a natural route between northern and southern mountains.

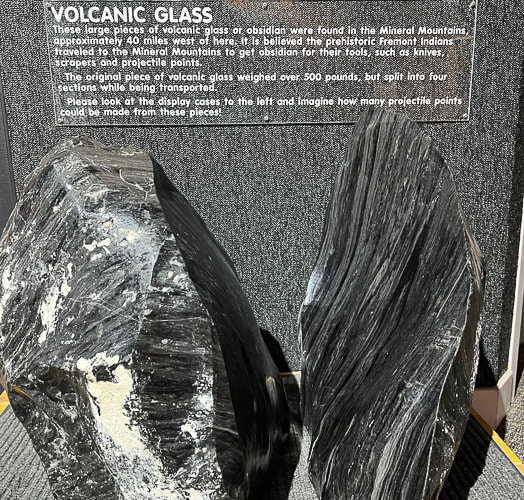

Voluminous amounts, ~ 150 cubic kilometers of ash flow explosively extruded from present-day Mt. Belknap to the south to fill the ancient Clear Creek Valley 19 million years ago. The ash was so hot - at least 1,100° F - that it "welded" and produced solid rock - hence the name "welded tuff." This rock, on which the Fremont peoples carved their petroglyphs is called the Joe Lott Tuff, named for an early Mormon pioneer who settled in this Canyon, building a cabin with orchards in the 1880's. When you look closely at this rock you can see the angular rock fragments of granite, biotite, feldspar, and pumice.

Petroglyphs carved into tuff at Fremont Indian State Park.

Being the geology nerd I am, the towering columnar cliffs, part of the Joe Lott Tuff near the east end of Clear Creek Canyon Road proved interesting. The six-sided columns are broken off at various heights along the walls where weaker bonds in the rock succumbed to erosion. These are jointed ignimbrites - thick, massive, lava-like sheets of volcanic rocks made mostly of glass particles. The process for this columnar jointing: volcanic eruption and ash flow --> cooling lava --> stress caused by cooling --> contracting lava forming cracks --> growing crack perpendicular to surface of flow --> columns are formed --> erosion and change --> columns break and tumble.

Columnar jointing in the volcanic Joe Lott Tuff. When this lava flow was cooling, vertical fractures developed to create the six-sided columns. Clear Creek Canyon has cut down through this tuff; erosion continues causing the columns to fall.

Claret cup hedgehog cactus and circular petroglyph on the Canyon of Life Rock Art Trail.

I liked the many petroglyph sites and their variations; some were close to the road but most involved short-distance hikes, enough to keep us busy the entire day. Outdoor interpretive signs at the museum present a time-line of the petroglyphs in this canyon and key components to look for in the designs made during different time-periods, with the Great Basin Abstract style being the oldest type (1,000 B.C.E.) in this area.

Fremont Indian State Park Petroglyphs

Cave of a Hundred Hands has 31 handprints. Metal bars protect it from further defacing.

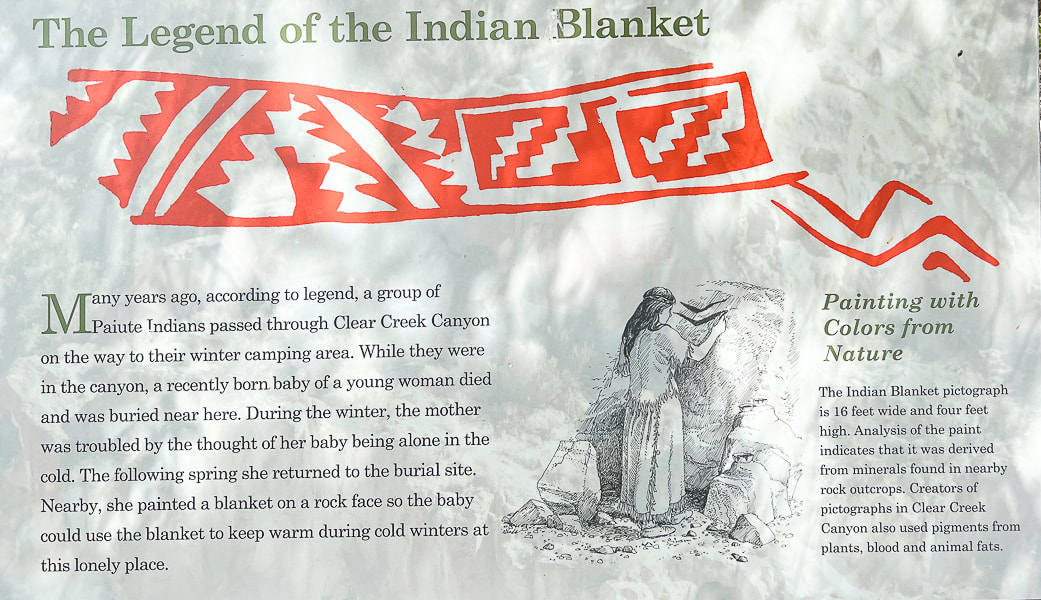

Unless you want to climb the rocks across the freeway, you view this pictograph from binoculars or the view pipe provided at the viewpoint. It's called a blanket because it reminded the first Mormon Settlers of a blanket design.

Castle Rock Campground (Map)

Castle Rock Campground is located just a few miles from Fremont Indian SP, in the volcanic Tushar Mountains. Last year we shared this range's highest peaks, Delano Peak and Mount Holly, with mountain goats in a wind storm. It felt good to be among the pines, cottonwoods and junipers in this clean campground. Eroded rock towers, AKA "hoodoos" or in this case "castles" provide an interesting backdrop. Mix in the soothing sounds of Joe Lott Creek flowing near many campsites and you've got a relaxing, back-to-nature getaway. Geology Underfoot instructed us to go behind campsite 23 to view the sediments of the hoodoos from the Sevier River formation, deposited between 15 and 4 million years ago by streams and sculpted by wind, water and ice. Right away I saw a pile of white ash mixed with sediments on the ground along with dark grey rocks that had weathered out of the walls. These hoodoo walls, when touched, crumble easily because these sediments have poor cementation. Periodic ash fall deposits blanketed these sediments; you can actually see two bright white ash layers, one near the top and the other near the bottom of these hoodoos. Another striking feature of these hoodoos is their interesting shapes caused by vertical carving and channeling. This Clear Creek drainage was uplifted because of Great Basin faulting that continues today. This uplift produced a slope, and the stream was invigorated, washing away the soft, poorly-cemented rock of this formation. Where there is a weakness in the rock, a small channel is started; heavy rains become concentrated in these channels, causing them to grow. So, the Sevier River formation was deposited onto an eroded Joe Lott Tuff, illustrating the law of superposition in stratigraphy - that is, the older layer of rock is under the younger layer. This principle is turned on its head, so to speak, however in the presence of compressive thrust faults that push older rocks over younger rocks, but not in this area. Oh be Joyful This is the actual name of a trail out of Crested Butte, Colorado that Fred and I have hiked a few times in July among the wildflowers. "Joyful" and "grateful" describe how I feel when we get to explore these intriguing Utah places, are able to use our legs to see incredible sights in person, and our imagination to wonder about the person who carved the petroglyph in the tuff hundreds of years ago. We've got 30 more Geology Underfoot locations to explore, including Valley of the Gods, the Goosenecks of the San Juan River, and the Virgin Anticline. Plus getting up to more Utah summits! How are we going to fit everything in?

"One night, a full moon watched over me like a mother. In the blue light of the basin, I saw a petroglyph on a large boulder. It was spiral. I placed the tip of my finger on the center and began tracing the coil around and around. It spun off the rock. My finger kept circling the land, the lake, the sky. The spiral became larger and larger until it became a dance of stars in the night sky above Stansbury Island. A meteor flashed and as quickly disappeared. The waves continued to hiss and retreat, hiss and retreat. In the West Desert of the Great Basin, I was not alone."

Terry Tempest Williams - from Exploring the Fremont

Never Stop Exploring!

Sevier River formation - layers of basin-fill deposits

Crumbling hoodoos (left), and a close-up of large rocks embedded in the walls (right), indicating more powerful water flow caused by storm events when these were deposited.

A chunk of ash (foreground) mixed with sediments that has weathered out of the eroded Sevier River formation. Note the layer of white ash present near the bottom of these hoodoos.

Interesting shapes in the Joe Lott Tuff.

"Castles" at Castle Rock Campground. Large dark volcanic rocks that protrude from their walls attest to the power of water flow during large storm events.

Claret Cup Hedgehog

Tuff texture - honeycomb weathering

Joe Lott Creek - Trail #051 goes from the south end of Castle Rock Campground to the Silver King Mine interpretive area.

One source said that Joe Lott helped build the arastras that ground the silver ore produced from the mine.

References

Case, W. Geosights: Fremont Indian State Park, Sevier County, Utah (from Utah Geological Survey website, vo. 42 #2, May 2010. Cunningham, C.G., Steven, T. A. 1979. Mount Belknap and Red Hills Calderas and Associated Rocks, Marysvale Volcanic Field, West-Central Utah. U.S. Dept. of the Interior - Geological Survey. Fremont Indian State Park Trail Guide. State of Utah Office of Museum Services. The Historical Marker Database - Pioneering Utah Madsen, D. B. 1989. Exploring the Fremont. Utah Museum of Natural History. Orndorff, R.L., et al. 2006. Geology Underfoot in Southern Utah. Mountain Press Publishing Company, Missoula, Montana. Simms, S. R. 4/22/2016. The Fremont Period. From historytogo.utah.gov website.

2 Comments

|

Categories

All

About this blogExploration documentaries – "explorumentaries" list trip stats and highlights of each hike or bike ride, often with some interesting history or geology. Years ago, I wrote these for friends and family to let them know what my husband, Fred and I were up to on weekends, and also to showcase the incredible land of the west.

To Subscribe to Explorumentary adventure blog and receive new posts by email:Happy Summer!

About the Author

|