|

Outstanding hike accessing the spectacular White Mountain's Franconia Ridge and beautiful waterfalls. On Mount Lafayette's granite at 5,249' with Mount Lincoln behind us on Franconia Ridge. Trip Stats

Location: Northern New Hampshire - White Mountains - Franconia Range. Distance/Elevation Gain: 8.9 miles roundtrip/3,800'. Mount Lafayette = 5,249'. Mount Lincoln = 5,089'. Difficulty: Strenuous Class 1 Maps and Apps: All Trails, National Geographic White Mountain National Forest West Map Date Hiked: July 3, 2024 Trailhead: Bridle Path/Falling Waters Trail on the east side of I-93 in Franconia Notch. Geology: (igneous intrusive rocks)

Useful Links: Appalachian Mountain Club - Greenleaf Hut Mountain Weather Forecast Hike Summary ascending Bridle Path Trail: 0 - 0.2 miles: parking lot at Franconia Notch to intersection of Old Bridle Path and Falling Water Trails 0.2 - 2.9 miles: Old Bridle Path Trail to Greenleaf Hut 2.9 - 4.0 miles: Greenleaf Trail to Mount Lafayette summit 4.0 - 5.7 miles: Mt. Lafayette to Little Haystack Mountain (Franconia Ridge/Appalachian Trail) 5.7 - 8.9 miles: Little Haystack to parking lot via Falling Waters Trail This guy had just climbed over the steep rocks on Falling Waters Trail to the top of Little Haystack Mountain. The owners assured us he was doing ok! On Top of New Hampshire Again, After 25 Years There's lots of reasons why this New Hampshire loop hike rates a 4.9 out of 5 on AllTrails: beautiful forest, three peaks to summit, a fun ridge (part of the Appalachian Trail) with spectacular views, waterfalls, and just enough challenge. The trailhead is just off I-93. The historic Greenleaf Hut at the base of Mount Lafayette allows you to refuel and replenish your water. We return to our old "stomping grounds" 25 years later - we hiked many summits and trails in the Whites and other ranges back in the late 1990's. We have great memories of hiking in all New England conditions - gorgeous autumns, buggy summers and icy winters. We bought our MSR snowshoes there and continued to use them when we moved to Idaho. Fred proposed to me on Mt. Cardigan, and we were married in Nashua in 1999.

Trailhead sign at large parking lot in Franconia Notch, just off of I-93. At the first intersection with Falling Waters Trail and Old Bridle Path - bridge spanning Walker Brook. Walking up Old Bridle Trail Greenleaf Hut finally emerged from the forest. It's full-service season is end of May through mid-October. You can reserve a bed in the unheated bunkhouse and get a full breakfast and dinner and naturalist programs. Another 1.1 mile steep climb brought us to Mount Lafayette's west ridge and the highest elevation for the loop, and also a huge prominence of 3,320 feet. That rivals the west's mountain prominences! These Appalachian Mountains look a lot different than the raw and jagged ranges of the west like the Rockies because they are much older, rounded and eroded. Even though Lafayette is 1,000 feet lower than famous Mt. Washington, New Hampshire's tallest, it still feels like you are on top of the state with spectacular views. On Lafayette's broad summit, hikers lazed in the sun and great weather. The hike along Franconia ridge, part of the Appalachian Trail was glorious. Great to see so much emerald green! We saw the familiar krummholz trees - brought us back to memories of hiking these mountains so many years ago. We had experienced some of the harsh conditions these stunted trees are subjected to on a few hikes - cold winds, snow and ice. By the time we reached our third summit of the day, Little Haystack Mountain at 4,760 feet, we were ready to descend via Falling Waters Trail with no idea the beauty we would see in a few miles. Steep boulders and rocks made the initial straight-down descent slow. As switchbacks appeared, we came upon the soothing sound of Dry Brook which was anything but dry. I see why hikers would prefer to ascend via Falling Waters Trail because you cross and walk in this stream for awhile - the rocks were slippery. Dry Brook descends with a series of beautiful falls. Stunning Cloudland Falls drops down several rock ledges. A light yellow dog named "Lemon" (I wish I would have taken his photo!) needed help from his owner to navigate the slippery rocks. I wished we could re-hike more New Hampshire peaks. I'd choose New Hampshire if I had to live on the east coast, but my heart still lies in America's grand, dramatic and often mysterious southwest. First view of Mount Lafayette (far left) and Mount Lincoln (center) on Franconia Ridge. Approaching Greenleaf Hut with Mount Lafayette rising above it. The hike continues on Franconia Ridge to the right to climb Mount Lincoln. The Greenleaf Hut, built in 1930, is an off-the-grid facility where you can stay in one of the bunkrooms with meals included, is located along the Old Bridal Path. Greenleaf Hut marks the end of the Old Bridal Path at the intersection of Greenleaf Trail, then climbs 1,000 feet in 1.1 miles to Mount Lafayette summit (above Fred in the photo). Greenleaf Trail begins further north off the I-95 adjacent from the New England Ski Museum. Getting closer to Lafayette's summit: Cannon Mountain Ski Area in Franconia Notch in the distance. Getting there! Mount Lafayette's summit On Franconia ridge looking northwest at glacier-carved valleys. Approaching Mount Lincoln - elevation 5,089 feet. Appalachian Trail/Franconia Ridge approaching Little Haystack Mountain. Mount Liberty and Mount Flume further along the ridge. Cloudland Falls on the Falling Waters Trail Bunchberry, or Creeping Dogwood On the upper portion of Falling Waters Trail. On the Falling Waters Trail.

7 Comments

Remote route-finding on Earth's largest landslide to a huge panorama of southern Utah.

Related

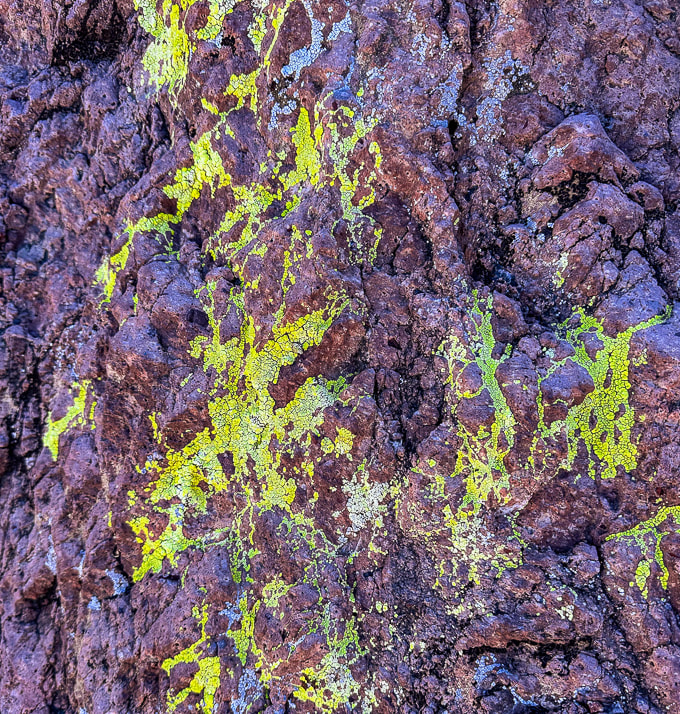

Imagining a Natural Catastrophe Still feeling energized after our Grand Canyon rim to rim hike, we decided to maintain our hiking fitness and get out of St. George's heat to hike a remote peak. I often go to Stavislost website to get ideas. Sandy Peak looked like a great opportunity for us to explore more of the forested Markagunt plateau near Cedar City, Utah. The rocks on Sandy's summit are just a microcosm of Earth's largest landslide - covering at least 1,600 square miles of southwestern Utah's high plateaus. It's called the Markagunt gravity slide, a catastrophic event that happened 20 million years ago when the surface of a huge volcanic field collapsed and slid southward for many miles, placing older rock on top of younger rock. "Markagunt Megabreccia" is the name of this rock unit. Breccia refers to jumbled angular rock fragments cemented together by a fine-grained matrix, with "mega' referring to fragments that are larger than one meter length. Catastrophic events like volcanic explosions create breccias. "Markagunt" is the Paiute word for "Highland of Trees". It resides in the Colorado plateau province. Cedar Breaks National Park rises from one of its highest points. Our Route: Avoiding the Steep Climb until it got Really Steep We parked just off the Old Spanish National Historic Trail in Upper Bear Valley. Locally, it is a nice graded road out of Paragonah that is also named Forest Road #077, Markagunt Plateau Trail and Bear Valley Road. 0 - 1.3 miles - walk southeast over Bear Creek right after parking, then walk up road (not numbered) that leads around the knoll to the east and drop into Ashton Creek at when it turns to the right (south). 1.3 miles - 2.9 miles - walk up Ashton Creek. 2.9 miles to summit - steep walk up Sandy's west slope, avoiding the top of the long ridge just to the north of the summit. We couldn't see Sandy Peak from the road approach. If I were to do this hike again, I would get out of Ashton Creek sooner and climb the first ridge on the left (east) I could see, which leads easterly to intersect with Sandy's north ridge. In the creek, we saw what looked to be a hunter's path (found a camera on a tree and a salt lick nearby) that led through a nice forest of pines, aspen and meadows, although we had a bit too many mosquitos. Getting on the ridge sooner out of Ashton Creek would have probably meant less bushwhacking. The steep walk to the top on Sandy's western flank was riddled with deadfall, rocks, and vegetation, adding to precarious footing at times. Maneuvering around rough volcanic blocks at the summit was fun. The view was huge. To the north, we saw smoke from a fire just south of the incredible Tushar Mountain range, and to the southeast the orange rocks near Bryce Canyon. This area of the Markagunt Plateau, squeezed up between Parowan Valley to the west, and the Panguitch Valley to the east has lots of trails, mountains, and mountain-bike friendly roads to explore. Gotta get back there! Visions of a Centro Woodfired Pizza got me through the last bit of route finding out of the creek. Per tradition, after hikes in this area, we went to this restaurant in Cedar City. Route-finding, wilderness, amazing view, pretty tough hike (at least for us), great pizza and great beer makes for the perfect day. Life is good! Caltopo Map and profile of our GPX tracks. North at top of map. Google Earth image of our tracks. Figuring out our route from Ashton Draw southeastward to Sandy Peak. Road leading southeastward from Old Spanish Trail (FR 077) toward Ashton Creek. This could be driven by a 4 x 4. Point where road turns right and we dropped down into Ashton Creek, 1.3 miles from where we parked. Sandy Peak not visible, but the long, lighter-colored rise just north of Sandy is poking out between two cone-shaped rises to the right of Fred. White columbine in Ashton Creek. Following cow paths in Ashton Creek until we found a wider trail (hunters' ?) that began on the right side of the creek to cross over to the left. Really nice hike up Ashton Creek, as long as you stay on the trail! Sandy Peak finally comes into view, but we were on the wrong side of the creek, so we went down and crossed, then went up the steep slope to the saddle just to the left of the peak. Looked like buck rub on these new aspens to us. Monument plant growing on slope with Sandy Peak at the top. The last time I saw Monument plant was on Mackay Peak in Idaho. Yep, it's a steep and rock-filled slope! Looks like layers of this volcanic mudflow breccia have separated or spalled from larger rock. Sandy Peak summit looking northward toward the Tushar Mountain range and a fire south of it. Descending into Ashton Creek, with lots of aspens. We are parked in Upper Bear Valley, at top of photo. Above this valley is Cottonwood Mountain to the west, where there are more trails. The East Bear Valley Fault runs the length of Upper Bear Valley. References

Biek, R.F., et al. Geologic Map of the Panguitch 30' x 60' Quadrangle, Garfield, Iron and Kane Counties, Utah. 2015. Map 270DM - The Utah Geological Society. Hacker, D.B., et.al. Catastrophic emplacement of the gigantic Markagunt gravity slide, southwest Utah (USA): Implications for hazards associated with sector collapse of volcanic fields. 2014. Geology vol. 42 #11. Sweet single track in the Kaibab Plateau's glorious high forest. Related Riding instead of Hiking We decided to switch up our usual mode of adventure - hiking - and get on our mountain bikes. After our epic Grand Canyon rim to rim in one day journey a few weeks ago, we noticed the beauty around Jacob Lake and GC's north rim in northern Arizona. Only a few hours drive from St. George, Utah, we got out of the heat to explore the cool, aspen-filled forest on the Kaibab plateau. So many aspens that it reminded me of Colorado high country. We stayed at Kaibab Lodge, five miles from the entrance to the north rim of the Grand Canyon National Park in a spartan "hiker's" cabin, the last place available there. Maybe a rim-to-rim hiker had cancelled at the last minute. The dinner and breakfast buffets were a bit spendy, but then again this is a pretty remote location. The Arizona National Scenic Trail links Mexico to Utah through 800 miles of prime Arizona deserts, mountains, and canyons. It's divided into 43 sections, or "passages." At the Mexico border, it begins in the Huachuca Mountains, trekking through grasslands to gain 3,000 feet to a ponderosa pine forest. The final passage is through Buckskin Mountain to the Utah border, where you can see the Vermillion Cliffs. It's open to hikers, mountain bikers and equestrians. We rode a gorgeous section of this trail through pristine forest and meadows in the Kaibab National Forest on a splendid single track to a viewpoint of the east rim of the Grand Canyon, making a loop by riding back on perfect gravel roads. No other vehicles - we had it to ourselves. The day before this, we just picked gravel roads to explore and ended up at an old cabin, possibly a line shack for ranchers. Our friend Jeff is an avid mountain biker. We hiked the rim to rim trail with him. When I showed him photos of this single track, he said, "Looks great. Let's go." That's the spirit! Looking forward to another northern Arizona adventure! A journey through one of the World's Seven Natural Wonders. Standard north → south route for Grand Canyon Rim to Rim in one day (North Kaibab Trail and Bright Angel Trail)

Total Distance = 23.5 miles North Kaibab Trail = 14 miles/5,700 feet loss. Bright Angel Trail = 9.5 miles/4,350 feet gain. Note: I've seen various estimates of "net elevation gain" that are higher. Since there is not any major regaining of lost elevation, I am estimating gain by difference between Colorado River and south rim. Elevations: north rim = 8,200 feet, south rim at Bright Angel Trailhead = 6,850', Colorado river = 2,500'. Date Hiked: May 23, 2024 Total elapsed time: 10:58 hours. Geology: The deepest rocks are metamorphic Vishnu Basement rocks on the lower part of North Kaibab trail as it enters the Box and Phantom Ranch and at Colorado River (Brama Schist, granite intrusive volcanics, pegmatite and aplite dikes). These are crystalline rocks (1.7 billion years), formed during Early Proterozoic time when continents were colliding, causing compression and mountain-building (orogeny). Theses are jumbled, interlayered shists and gneisses. Rim to Rim Resources: NPS: Critical Backcountry Updates - Grand Canyon NPS: Grand Canyon Backcountry Trail Distances Arizona State University. North Kaibab Trail - Nature, Culture and History at the Grand Canyon. Considerations: Fred and I recommend anyone undertaking this hike should train and be able to walk at least 15 miles continuously and hike 4,000 feet of elevation gain. We hiked this 23 years ago with 100-degree temps at Phantom ranch which slowed us down, but we had experience hiking in hot weather. "Endure. In enduring, grow strong." - Chris Avellone "It is a lovely and terrible wilderness, such a wilderness as Christ and the prophets went out into; harshly and beautifully colored, broken and worn until its bones are exposed . . . and in hidden corners and pockets under its cliffs the sudden poetry of springs." - Wallace Stegner Epic Adventure We did it! Three months of training on southern Utah trails, in St. George and Zion National Park, and on the Skyline Trail in Palm Springs helped Jeff, Fred and I conquer the Grand Canyon rim to rim hike. Two things helped us: training for distance and at least 4,000-foot of elevation gain, and we were lucky with weather. It was cooler than usual! To observe the Grand Canyon, one of the seven natural wonders of the world from its rim is a memorable experience. But to walk all the way through the depths of it - almost 24 miles from north rim to south rim along the clear and roaring Bright Angel Creek is epic. Your ability to tolerate a 50 or 60-degree temperature variation, drink enough water, and climb steep, relentless switchbacks will be tested. We took longer to do this hike this time (just shy of 11 hours), compared to our last time 13 years ago (9:50). I felt really tired the last mile up to Bright Angel Trailhead. I think I slowed Jeff and Fred down a bit! North Kaibab Trail → Phantom Ranch Lindy dropped us off at North Kaibab Trailhead on the north rim at 6:00 a.m. As we descended from a fir, spruce and ponderosa pine forest into a rocky color-layered paradise, she drove around to the south rim, descended 4 miles on the Bright Angel Trail to meet us later in the day. In the shadow of the north rim, we walked along verdant Roaring Springs Canyon to the bright yellow light below, reaching Supai Tunnel, the first restroom and water stop, at 1.7 miles. Wild roses bloomed against yellow and red walls. We didn't need a water re-fill until 5.4 miles down the trail at Manzanita Rest Area, a beautiful spot past Roaring Springs. We powered our way down the steep portion, through the wide Bright Angel Canyon, tracing the clear and loud Bright Angel Creek with its occasional waterfalls, hiking through Cottonwood Campground. The prickly pear were so full and healthy; it seemed the creek was flowing much more than we remember from our rim to rim hike 13 years ago. It appears the southwest has had more rainfall in the past few years. We hiked rim to rim 23 years ago and then again 13 years ago and it seems Bright Angel Creek was higher this year. We were happy to see Bright Angel Campground and Phantom Ranch at the bottom of the canyon where we re-filled our water and made sure to drink electrolytes. The temperature was 85 degrees. We took 20 minutes in the shade to eat and muster the energy to start the long, warm and steep hike to the south rim. The dark red, brown and grey Vishnu Basement rocks are one of my favorites of this hike, as you enter the core of the Grand Canyon. It forms the rough, contorted, massive base for the prettier rock layers above. It's not often that you get to walk in some of the Earth's oldest rocks; in this case the Vishnu schists, gneiss and granite are 1.7 billion years old. You get to see the rapids of the green Colorado River through the mesh floor of the long suspension bridge as it passes a huge swirling eddy near the shore, delivering you to the Bright Angel Trail and a long, arduous hike out. Water stops along the North Kaibab Trail: distances from North Kaibab Trailhead. Grand Canyon Critical Backcountry Updates

Phantom Ranch → Bright Angel Trail Water stops along the Bright Angel Trail

We finally reached Havasupai Gardens, our last water stop (we knew the resthouses above did not have water) with 4.7 more miles to go! Dousing my hat in the cold water from the "community" faucet and letting it drip down my head felt so good! Shortly after eyeing the south rim's steep cliffs above that will be our trail, we resumed and were excited to see Lindy, who had descended 4.5 miles to meet us. Climbing higher, along Garden Creek, legs are tired, yet the terrain gets more challenging. We step over countless old juniper logs and rock bars used to stabilize the trail on forever switchbacks. We are trying to make it in under 11 hours. Dozens of short-distance south rim hikers congest the last half-mile. Don't want to lose momentum. Endure and grow stronger! Lindy spotted an incredible sandstone boulder along the trail that has fossilized tracks in it. They are the oldest vertebrate tracks in the Grand Canyon and the earliest evidence of vertebrate animals walking on sand dunes. They date to 300 million years ago, when Arizona was a coastal plain near the equator. This article in Smithsonian has a great illustration of how this reptile walks laterally, creating the diagonal footprints: Fallen Boulder at Grand Canyon reveals Prehistoric Reptile Footprints. Fossilized footprints found in Manakacha Formation - 313 million years old. And then the land above the canyon opens up and we arrive at the rim - WE'VE DONE IT!! We walk victoriously to the Bright Angel Trailhead sign where Lindy snaps our photo. Margaritas, beer, and burgers follow. I'm grateful we trained for this epic hike. I'm even more grateful that I am able to do this hike and witness this natural wonder - up close and personal, step after step, one foot in front of the other. Standard route for Grand Canyon North Rim to South Rim in one day (North Kaibab Trail and Bright Angel Trail) Distances/Elevation gain/loss: North Kaibab Trail = 14 miles/5,700 feet loss. Bright Angel Trail = 9.4 miles/4,350 feet gain. Note: I've seen various estimates of "net elevation gain" that are higher. Since there is not any major regaining of lost elevation, I am estimating gain by difference between Colorado River and south rim. Elevations: north rim = 8,200 feet, south rim = 6,850', Colorado river = 2,500'. All Fired up! As Pat Benatar's song goes, we're "All Fired Up" for next week's Grand Canyon rim to rim hike! Her song is a fitting accompaniment to the goblet squat video below. Fred and I needed elevation training, so we went to Palm Springs, my old stomping grounds, and hiked the Skyline Trail for a gain of 4,700 feet, the same Bright Angel Trail gain on the south rim of the Grand Canyon. We encountered too much snow at 8,000 feet in the Pine Valley Mountains just to the north of St. George, preventing a good elevation gain. My last post, Grand Canyon Rim to Rim In One Day: Training in St. George, Utah, explains how we got creative with emulating distance and elevation. We did great on the Skyline; we're now ready for the big hike!

New goal: hike to the tram this October with some of our hiking buddies. Oh, the nostalgia and the beauty of this mountain! I'm grateful that I can still be hiking it 31 years later - let's say that the Advil this time was very helpful! La Verkin Creek Trail to Kolob Arch - Zion NP This long hike features attributes found in Zion National Park's main canyon, including an arch, sandstone cliffs and a river but without the throngs of people. It's in the northern Kolob Canyons section, has a spur trail to impressive Kolob Arch, and also meets up with the Hop Valley Trail, a route to the main Zion Canyon. We hiked 7 miles in to Kolob Arch and back for a total of 14 miles, the same distance as Grand Canyon's North Kaibab Trail. It drops down from the parking lot at Lee Pass Trailhead into the La Verkin Creek drainage. The same mileage as our Skyline Trail hike, but not nearly the same elevation gain. We've got one more training hike on Zion's West Rim Trail this week with Lindy and Jeff, and then we should be good to go for the Grand Canyon. We are lucky to have such inspirational places, some of the most beautiful on Earth, in which to train! Strengthening exercise for powerful hill climbing: Goblet Squats I have found that since I started doing CrossFit and working on strengthening my legs, I have more stability and power for steeper hiking. Goblet squats can be done with a kettlebell as well as two dumbbells, each resting on your shoulders. Strengthens your core (trunk) muscles, glutes and hips. Points to remember:

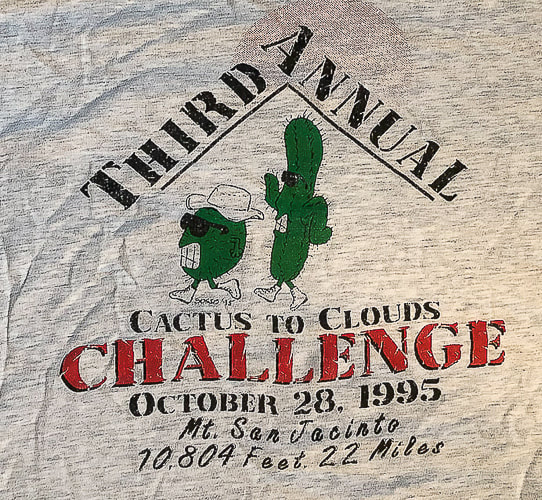

Forsyth Creek - Pine Valley Mountains in mid-May. It's a late spring here; ran into packed snow on the trail at 8,000 feet. Trees are just starting to bud. photos captured with my new Sony mirrorless camera. La Verkin Creek in Kolob Canyons section of Zion National Park. At the beginning of La Verkin Creek Trail - Kolob Canyons of Zion National Park. Jeff and Fred on La Verkin Creek Trail - Zion National Park. This morning was cold starting out - 31 degrees! Kolob Arch, 7 miles from Lee Pass on the La Verkin Creek Trail. La Verkin is the name of a nearby city between both entrances to Zion National Park. Origins for its name may have come from an alteration of the Spanish word for the nearby Virgin River -- la virgen. Mile #14 - on the way back to the Lee Pass trailhead! Beautiful Zion hike. Scott and Fred on the Skyline Trail overlooking Palm Springs and the Coachella Valley, California. Near the beginning of the Skyline Trail. Prepare before you go far on the Skyline! The steepest part is the "traverse" at the end of the hike. I have seen a person in serious trouble on one of our Cactus to Clouds hikes. Getting higher - overlooking Palm Springs. Oh beautiful yucca! At ~ 4,000-foot elevation on the Skyline looking at the final climb to the Palm Springs Aerial Tram on far ridge. One of the first views of the San Jacinto Wilderness, where the Skyline Trail that leads to the Palm Springs Aerial Tramway Mountain Station terminates on the ridge way up there! We are heading to the ridge on the right. Chaparral Yucca on the Skyline Trail with the Little San Bernardino Mountain Range across the Coachella Valley in the background. A good look at what is to come on the Skyline Trail. The tram station is just to the right of the arrow. Coffmans Crag, the white granite just below and to the right of the arrow, is a good landmark to see the final "traverse", a green and steep spot of trees to the left of it in this photo. The Skyline Trail is not one to be taken lightly. People have died on this trail. On one of our Cactus to Clouds hikes, a man caught up to us who had lost his hiking party. He was severely dehydrated - required a helicopter rescue. Left, right from top to bottom: Ribbon Wood tree (Adenostoma sparsifolium), Chaparral yucca, North Lykken trailhead sign, metal sign commemorating Jane Lykken Hoff, "trail boss" of the Desert Riders, contents of Rescue Box 1, Skyline warning sign, Rescue box 1, and boulder sign at the intersection of North Lykken Trail and Skyline Trail. Yucca and Ribbonwood trees. Celebrating long friendships with our hiking buddies in Palm Springs. I have known these friends for over 30 years! We have shared many miles on desert trails and many memories. Love you guys! from left to right: Scott, Vickie, Maria, Sue and Fred. Vickie, Maria and I are in the photo below - 31 years ago! The First Cactus to Clouds Challenge - October 1993

Summit of Mt. San Jacinto, 10,804'. From left to right: Sue Birnbaum, (don't remember his name), Roger Keezer, Maria Keezer, Ray Wilson, and Vickie Kearney seated in the middle. Getting creative with hikes in Southwestern Utah to prepare for the Grand Canyon. Grand Canyon North Rim to South Rim Hike Facts:

Standard route north to south (North Kaibab Trail and Bright Angel Trail). Distances/Elevation gain/loss: North Kaibab Trail = 14 miles/5,700 feet loss. Bright Angel Trail = 9.4 miles/4,350 feet gain. Note: I've seen various estimates of "net elevation gain" that are higher. Since there is not any major regaining of lost elevation, I am estimating gain by difference between Colorado River and south rim. Elevations: north rim = 8,200 feet, south rim = 6,850', Colorado river = 2,500'. Geology: Oldest rocks are Vishnu Schist, an early Paleoproterozoic basement rock (2 billion years ago) at bottom of Grand Canyon. Youngest rock is the Kaibab Limestone on the top of the rim, a cream and white sandy limestone. "By far the most sublime of all earthly spectacles . . . the sublimest thing on Earth." - Clarence Dutton referring to the Grand Canyon. Related Posts

On May 23, we will be walking Grand Canyon from its north rim to its south rim in one day - again. Fred and I first hiked this 23 years ago, to celebrate birthday #40 for both of us. We hiked it on our 50th. We talked about doing it for our 60th, but it wasn't until our friend Robin asked us to go that we got our motivation to train for rim to rim #3. Jeff will do it too, and Lindy will train with us but when it comes to the big day, she has generously offered to drop us off at the north rim and drive all the way around to the south rim to pick us up. Since January, Fred, Jeff, Lindy, Robin and I have been hiking the most challenging trails near St. George, Utah and in Zion National park. Creative planning like linking trails together ensures optimal distance and elevation training. We need to be able to cover 23 miles and a 4,500' gain for rim to rim. Just when your legs are tired from descending 14 miles on North Kaibab Trail, you face the biggest challenge: climbing up Bright Angel Trail for another 9.4 miles. And temperatures on the climb out can be hot, which was the case when we did this hike 23 years ago. We ended up soaking our hats in streams on the way up to cool off. Fred drank 9 liters of water! The next day, we hiked back to the north rim. Some of Our Training Hikes

Strengthening for Hill Climbing - Walking Lunge with Overhead Weight Climbing out of the Grand Canyon requires strong glutes! The most important function of your gluteus medius during hiking is to stabilize your pelvis to keep it level while standing on one leg (stance phase of walking). The stronger they are, the better protection for your knees, and the more efficiently they work, the less energy you waste. Walking lunges challenge your glute and core strength. Holding a weight over your head adds more challenge to your core musculature including abdominals and back extensors, as well as your shoulder girdle stabilizers (rhomboids, trapezius, serratus). Good training for scrambling hikes where you have to use hands to propel up rocks. Action: Hold dumbell or kettlebell overhead with elbow straight, next to your ear. Or, you could hold the weight in a "goblet" position next to your chest. Take a large step forward, that knee should not go ahead of your foot. Opposite knee taps the ground. Squeeze glute on stance leg to raise to lunge with opposite leg. Here's some scenes from three of our training hikes: Snow Canyon from Bottom to Top and Then Some: Berm Trail to Joan's Bones (12 miles RT, ~1600' net gain) Berm Trail → Padre' Canyon Trail → Red Sands Trail → West Rim Trail → Lava Flow Trail → Whiterocks Trail →Joan's Bones → car at Whiterocks Trailhead. Living near Utah's Snow Canyon State Park sure has its advantages. Each time I hike in this Navajo Sandstone paradise, I love it more. We started near where we live, caught the berm trail and walked to the Whiterocks Trail on the north side of the park, then walked east to almost the top of Joan's Bones. This route features gorgeous pools in cross bedded sandstone, soaring orange and red towers, petrified sand dunes, and pristine white sandstone slickrock strewn with black basalt boulders. Joan's Bones hike is on AllTrails (misspelled as "Jones Bones"). Snow Canyon training! Robin, Lindy and Jeff at top of Padre' Canyon. Scenes from Snow Canyon State Park, except upper right photo is from Joan's Bones Trail to the east. Jeff, Robin and Lindy on the Padre' Canyon Trail. Fred climbing up cliff band on Red Mountain Trail, backside of Padre' Canyon. Exploring off the Padre' Canyon Trail. Moss after a rain near Padre' Canyon. Hiking up toward Joan's Bones - basalt and sandstone. Descending Joan's Bones Trail. Reflection at Whiterocks Amphitheater Old juniper on Butterfly Trail in Snow Canyon State Park, Utah Old juniper image shot with my new Sony mirrorless, full frame sensor camera!! Zion National Park - West Rim Trail to Horse Pasture Plateau (10 miles, 3,000' gain). Right after the shuttle service opened in early March, Lindy, Robin, Jeff and I headed to Zion to get some elevation training in. Starting at the Grotto Trailhead, 4,300' elevation, we hiked up West Rim Trail, past Angels Landing to the entrance into Horse Pasture Plateau at 6,713', at the intersection with Telephone Canyon Trail. After regaining ~ 300' of elevation loss to and from, I calculated our gain to be ~3,000 feet. We hiked on some icy snow. Down in the canyon and at the plateau, temperatures were a bit chilly. Zion was not especially busy with visitors that day. We celebrated afterwards in Springdale with beer and burgers at Porter's restaurant. A view of Walter's Wiggles, tight switchbacks up through Refrigerator Canyon on the way to Angels Landing. Named after Walter Ruesch, Zion National Park's first superintendent who helped construct the trail in 1926. One of the last switchbacks up to intersection of West Rim Trail and Telephone Canyon Trail on Horse Pasture Plateau. Looking at Zion's West Rim Trail and Angels Landing (orange fin beneath Great White Throne). Aprés hike brew and burgers! More scenes from Zion, and Jeff on Walter's Wiggles on the way to Angels Landing. Ascending Walter's Wiggles, Refrigerator Canyon to the right. Ivins and Santa Clara, Utah: Suicidal Tendencies Trail and the "Badlands." The "badlands" is my nickname for the landscape west of Land Hill in Ivins, and east of the Beaver Dam Mountains because it reminds me of South Dakota's badlands. A spectacular view of this formidable-looking red and white striped land cracked by crooked canyons and washes and plateaus with well-established biological soils can be savored from the top of Land Hill. We hiked Wittwer Canyon, a major tributary that washes into Santa Clara River. Fred and I put together a 10-mile hike that linked the petroglyph trails on Land Hill to cross the Santa Clara River, to wander through the "badlands" to find a way to link to the Barrel Roll Trail in the Cove Wash Trails. In just one hike, Fred and I saw all the "cool stuff on this trail," (see photos below) and then some. A conglomerate boulder hanging on the steep wall under Land Hill looks like it has embedded dinosaur tracks. I called the local paleontologist; stay tuned!

We're fortunate to have Colorado Plateau hiking to the east of us and Mojave Desert hiking to the west. One day we hiked the 11-mile Suicidal Tendencies, a popular mountain bike trail with scary drop-offs. The more we hike this part of Utah, the more we find to explore. Not only are the views magnificent - black lava flows blend with red and orange cliffs, signs of past cultures and geological events adds a lot character to this part of southern Utah. My next post (rim to rim training, part 2) will highlight another Zion hike and Red Mountain Traverse. Getting Ready for the Big Day! Keep On Exploring!!! Cool Stuff on the Trail One angry rattler, Santa Clara petroglyphs, preserved ripples, beaver dam on the Santa Clara River, dinosaur tracks(?) in Shinarump Conglomerate, a well-developed biological soil crust in the "badlands." The "badlands" west of Ivins, Utah. Top of Suicidal Tendencies is on the left butte. Fred and I descended down to the cottonwood trees below and crossed the Santa Clara River, found a path through the badlands to the left and looped back using Cove Wash trails. Jeff climbing a dry waterfall in Wittwer Canyon, finding our way up-canyon. Wittwer Canyon: upper part is located in the Shivwits Band of Paiutes Land. Wittwer Canyon - Santa Clara River Reserve on a cold and windy day. Western cliffs along the Santa Clara River - the rattlesnake is up there! Fred and I found a shallow crossing on the Santa Clara. Jeff walking toward top of Suicidal Tendencies Trail (green plateau). From Suicidal Tendencies Trail looking north across "badlands" to Red Mountain and Ivins, Utah. Snow-covered Pine Valley Mountains on the right horizon. On the top of Suicidal Tendencies - a survey marker that has "Santa Clara" and "1954" stamped onto it.

Unravelling the mysteries of two unique, older petroglyph sites that I found along the Santa Clara River in Utah. Abstract petroglyph overlooking the Santa Clara River in the Santa Clara River Reserve.

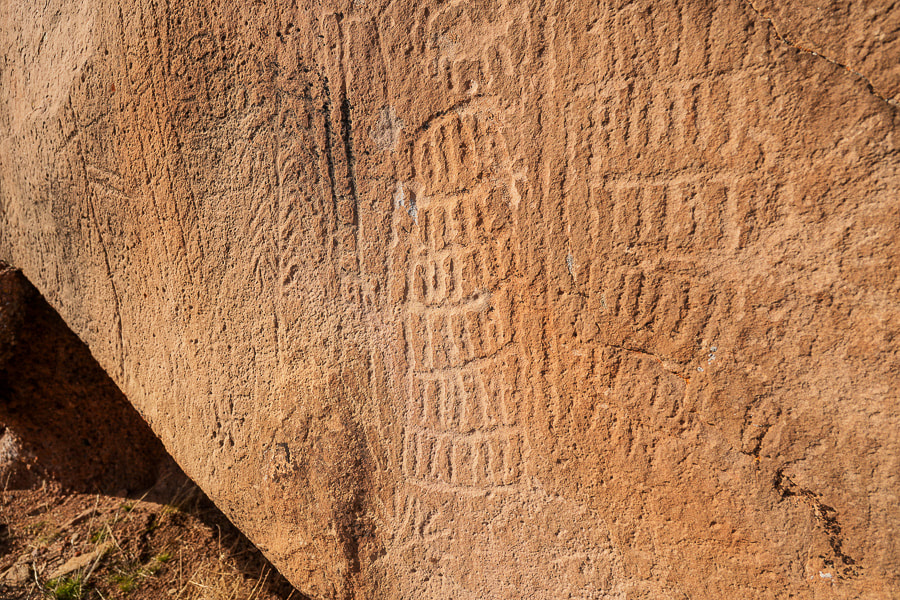

This design closely resembles an Ancestral Puebloan (formerly Anasazi) petroglyph found in Arizona. Checkerboard designs are associated with Glen Canyon Style 5 made before 1050 A.D. by Ancestral Puebloans including Basketmaker cuture. Related Posts:

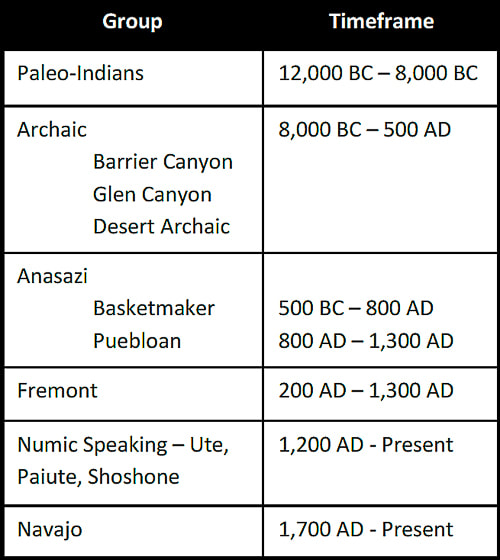

Trip Stats Location: Santa Clara River Reserve near Ivins and Santa Clara, Utah - Land Hill. Trailheads: Anasazi Valley Trailhead (north) and Tukupetsi Trailhead (south). Distance: The distance that includes all of the petroglyphs described here is ~ 5+ miles (top of Land Hill and along the Santa Clara River). Some interesting books: A Field Guide to Rock Art Symbols of the Greater Southwest by Alex Patterson. Early Rock Art of the American West: The Geometric Enigma by Ekkehart Malotki and Ellen Dissanayake. The Rock Art of Utah by Polly Schaafsma Links: Santa Clara River Reserve Map Santa Clara/Land Hill is designated as an Area of Critical Environmental Concern (ACEC). Geology: Petroglyphs are located in the oldest rocks of the Santa Clara Quadrangle Geologic Map: - Shinarump Member Upper Sandstone unit and Shinarump Conglomerate Member of the Chinle Formation: Upper Triassic (~ 200 million years ago). Petroglyphs in sandstone and dinosaur tracks in conglomerate. -Cliffs below Land Hill along the Santa Clara River: Upper Red Member of the Moenkopi Formation: Lower Triassic (~ 250 million years ago). The fascinating rock art on the Tempi'po'op Trail (Anasazi Valley Trail) in Ivins, Utah, made by the Virgin Ancestral Puebloan and Southern Paiute cultures thousands of years ago can be discovered for more than two miles along the cliffs of Land Hill, overlooking the Santa Clara River. Additionally, many more petroglyphs are pecked into huge boulders and sheer walls beneath Land Hill, next to the river. Each time I explore this part of the Santa Clara River Reserve, I find new petroglyphs. On a recent wander, I discovered two intriguing petroglyph sites that I had previously passed by.

Five bighorn sheep on the right side of the boulder along with two large columns made with parallel vertical lines bisected incrementally with horizontal lines are pecked next to the older-appearing, lichen-filled and more highly eroded geometric glyphs. Who made these abstract/geometric petroglyphs and what do they "mean"? Various theories include shamanistic visions, recording of phosphenes, and communication of vital information like water sources. The Paiute word for them, Tumpituxwinap, translates roughly as "storied rocks."

Huge boulder on flat area near Santa Clara River predominated by abstract/geometric petroglyphs, possibly of the Great Basin Curvilinear and Rectilinear style. The right side of the boulder; these deer and sheep petroglyphs seem to be younger than those on the left side because they are not as eroded. The plant-like image (upper left) looks like a corn tassle to me. Petroglyph on top of boulder (left). It reminds me of a necklace: it's similar to those that are pecked into a boulder nearby. It looks like a chain of circles, which might indicate the Great Basin Curvilinear style. In Search of the Rattlesnake Petroglyph. Back of boulder with what I could find as the easiest route to the top.

Phosphenes are lately being proposed by scientists as the catalyst for the creation of abstract designs. All humans experience phosphenes that occur during hyperventilation, migraine headaches, meditation, use of hallucinatory drugs, fatigue and hunger and pressure put on a closed eye. The idea is that geometric petroglyphs and pictographs depict an innate visual grammar (Engel in Fein, 1993) that we all share, ingrained in the biology of our brains. My earlier post Corn Springs Petroglyphs: Vision Quests, Steamboats, and Ringing Rocks explains a few theories for the creation of the Western Archaic Tradition rock art. The Santa Clara Boulder and the "Abstract Enigma" I found two photos of petroglyphs very similar to that of the spoked circle design on the large boulder by the river. One illustrates the Western Virgin Kayenta style and the other illustrates Great Basin Carved Abstract petroglyphs. This spoked circle seems less prevalent than the spiral petroglyphs that appear frequently on the cliffs above the river. Great Basin Abstract tradition rock art spans the Archaic and the Late Prehistoric (8,000-150 years ago). The Great Basin Carved Abstract style occurs in St. George, Utah area. It's characterized by purely geometric petroglyphs that fill boulders so that little unmarked space is left. Art includes various circle configurations, grooves, grids, lattices, herringbone shapes, ladder-like shapes, chevron, hatchmarks and dots. This boulder along the Santa Clara River contains some of these elements. Since this style is found not only in Nevada's Great Basin, but throughout the American West, some scientists call it "Carved Abstract". The rows of vertical lines cut with horizontal lines, surrounded by a line are similar to "gridiron" petroglyphs seen in New Mexico. The parallel wavy lines above the spoked circle are considered Great Basin Curvilinear, which I read is another way to say Great Basin Carved Abstract. The grids and cross-hatchings, and perpendicular form is known as "rectilinear." These styles are associated with the Archaic style and also occur in styles associated with Puebloan and Fremont groups. Two authors state that the Great Basin Abstract petroglyphs appear to be made as a part of "magic hunting ritual and were related to subsistence practices..." (Heizer and Baumhoff). Abstract designs predominate this style, with a limited depiction of animals. The most common animal portrayed is the bighorn sheep. I also noticed what appeared to be cupules (pit and groove style) on the back side of the boulder. Or are these holes just natural weathering? Or both? One pit placed on the side of the boulder looks too symmetrical to be made by weathering. Theories for their creation include fertility enhancement and the use of powder produced from making them. Cupules or natural weathering? Cupules are associated with very early Carved Abstract Style. It's assumed that cupule sites identify places of significance. Anthropomorphic (Human-like) petroglyph on a flat boulder near the Een'oog Trail and the cliffs overlooking the Santa Clara River. Size is ~ 14 inches tall. Is a Snake Biting the Figure with the Drooping Hands? The second amazing petroglyph I found is on top of Land Hill along the Een'oog Trail, on the cliffs above the Santa Clara River. It's totally repatinated, blends into the rock, so it's easily missed (see above). Its drooping arms, termed "pendant" by scientists, round head, hair bobs, long rectangular or slightly trapezoidal (wider at the shoulders), and feet and hands pointing down match the description I found of the Anasazi Basketmaker culture - 500 BC - 800 AD. The term "Anasazi" has now been replaced by "Ancestral Puebloan." A serpentine-like line winds its way from the left side of the figure to the figure's leg. These “representational” styles are typically associated with Fremont and Western Puebloan cultures (ca. 2,000-750 years ago) in southeastern Nevada, Utah, and the Colorado Plateau. These semi-horticultural groups made rock art that featured human-like forms portrayed by trapezoidal, rectangular, or triangular body shapes. These were often portrayed with bodily decoration such as headgear, jewelry, or decorated clothing. In my research, I found the Classic Vernal-Style (a sub-set of Fremont Style) Anthropomorph has large heads and trapezoidal torsos with well-defined extremities. The Fremont style tends to have round earbobs and arms and hands held down, commonly with splayed fingers. In western Utah, there is an intermix of Great Basin Curvilinear and Fremont styles. Ancestral Puebloan farmers lived in the Land Hill area in permanent settlements ~ 1,000 years ago. The Santa Clara River gave them a good water supply to irrigate their crops. During A.D. 700 - 1100, population on Land Hill thrived, but then around 1200 A.D., population decreased possibly due to changing climatic conditions. I found an old corn cob in a grassy area beneath the cliffs next to the river (see photo below). Every kernel had been removed. It couldn't have survived hundreds of years! Or could it have been exhumed after the record-setting rains of 2022-2023 that caused a major landslide at an area close to it? A Land Rich in Culture, Stories, and Mystery Dinosaur tracks have been documented on Land Hill. At first glance, you wouldn't imagine that the Santa Clara River Reserve holds so many stories among its cliffs, plateaus, and rock art. If you look closely, you will see abstract and representational communication made by different cultures during different times. In my quest to figure out who made these fascinating petroglyphs and why, I realize that if anything, they still remain an enigma. I'll let you know if I find the dinosaur tracks and more corn cobs! Keep Exploring! When I went to look at the figure with the round head and the ear bobs again (lower right), I shared the petroglyph rock with a goose. Petroglyphs (walls on right) overlooking the Santa Clara River. Land Hill on the right and a path that runs along the Santa Clara River. Beaver Dam Mountains in the distance. Petroglyphs are found on the flat surface rocks, in the steep cliffs of Land Hill, and on boulders along the river. Finding a route down from the top of Land Hill with my friend Laura. We are headed to the Santa Clara River below. Notice the Shinarump conglomerate rock in the right foreground. When we got near the river, we found this boulder with what looks like Great Basin Curvilinear style and a family of anthropomorphs (human-like) figures. Petroglyphs on the Anasazi Valley Trail in Ivins, Utah. The Glen Canyon Style 5 (Ethnic groups are Early Puebloan and Basketmaker). Bighorn sheep have large rectangular bodies disproportionately large compared to their small heads, tail and legs. Laura and some really cool sandstone boulders along the Santa Clara River. Some Cool Stuff on the Trail Clockwise from upper left: slickensides created from scraping against other rocks in a fault, bivalve fossil near the Een'oog Trail, a corn cob, a desert-varnished panel on an eroded sandstone boulder. Sandstone boulder detail. References Bureau of Land Management. Land Hill Heritage Site. Malotki, Ekkehart. The Rock Art of Arizona: Art for LIfe's Sake. From website: Bradshaw Foundation. Mangum, M.E. 2018. Lithics and Mobility at Land Hill and Hidden Hills: A Study of the Stone Tools and Debitage at Sites in the Santa Clara River Basin and on the Shivwits Plateau. Brigham Young University ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 2018. 28107515. National Park Service. Reading Rock Markings. Schaafsma, P. 1971. The Rock Art of Utah. Scotter, T. Bowen , N. 2017. The Rock Art of Utah. The Nevada Rock Art Foundation - Styles and Themes Willis, J.C., Hayden, J.M. 2015. Geologic Map of the Santa Clara Quadrangle, Washington County, Utah. A New Year's Day 2024 journey through pinyon-juniper woodland on top of Red Mountain near St. George, Utah to a spectacular Snow Canyon overlook. Looking north over Snow Canyon State Park from "On Top of the World" on Red Mountain. Pine Valley Mountains on the horizon. View of Red Sands Trail (right) in Snow Canyon SP from a previous hike - Red Mountain Primitive Trail. Trip Stats - Ivins Trailhead

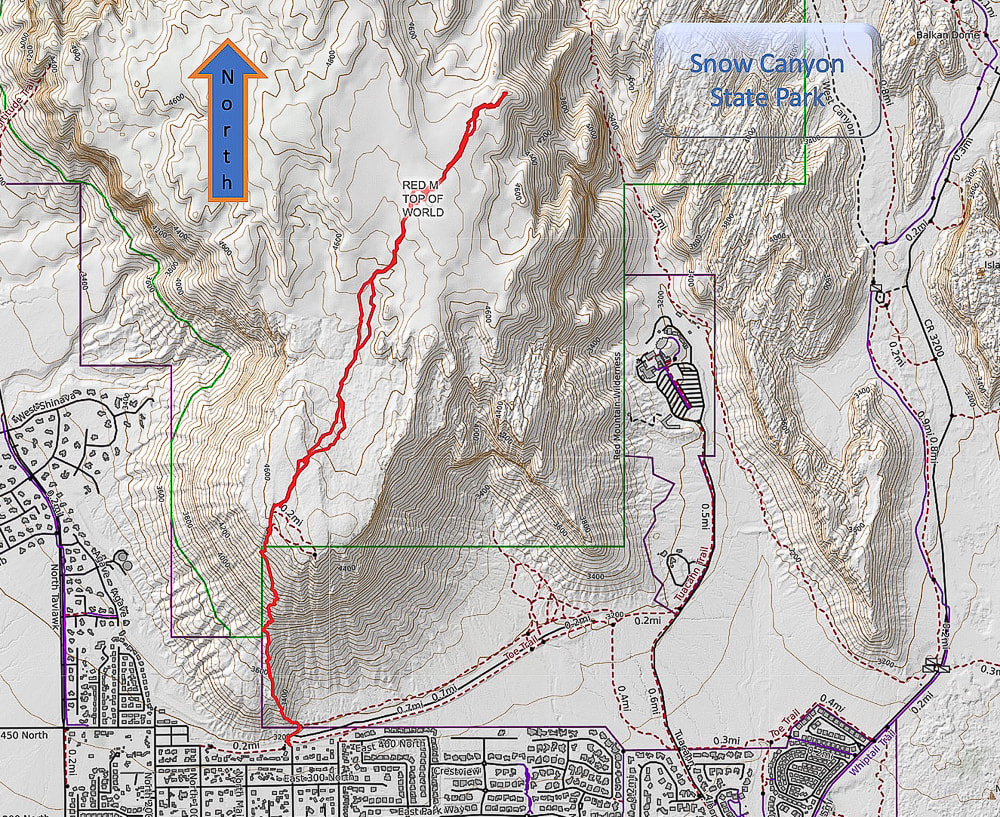

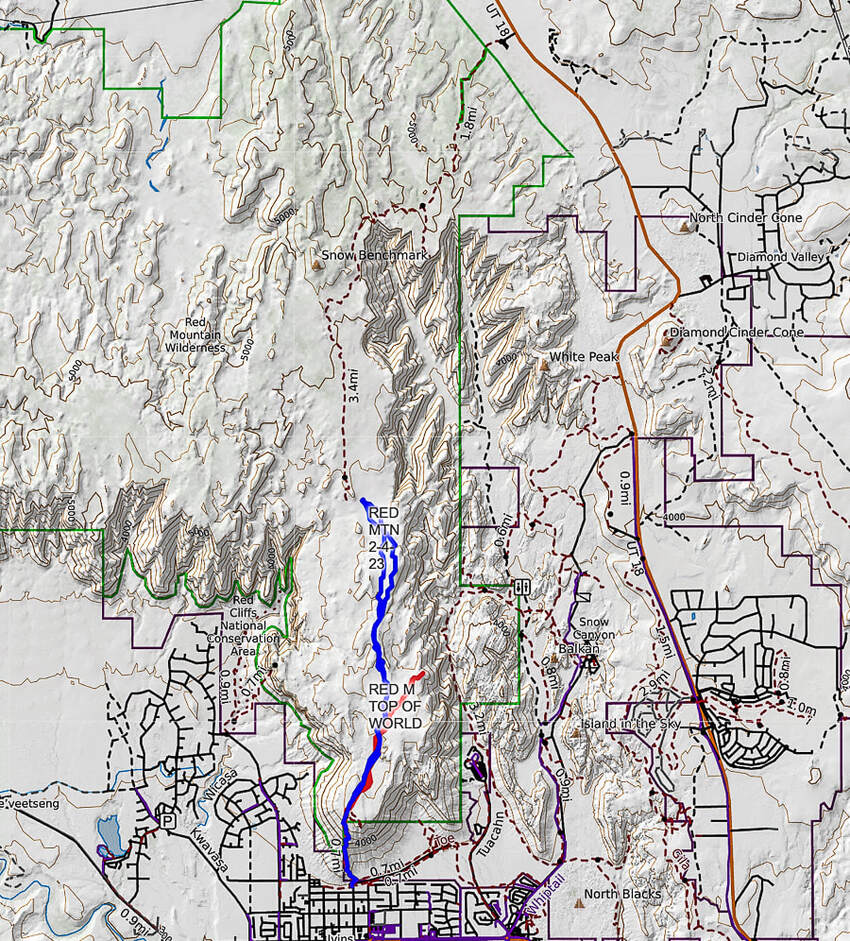

Overview/Location: This quiet, cross-country excursion through the gorgeous Red Mountain juniper woodland biome brings you to an expansive view of southern Utah's Snow Canyon State Park. A remote island of solitude in the Red Mountain Wilderness elevated above the cities of Ivins and St. George. Distance/Elevation gain: 5 miles out and back/1,575'. Coordinates/Elevation: Red Mountain Trailhead = 37.17519, -113.67755 (3,190'). Southern Red Mountain Primitive Trail out of Ivins. Top-off at 0.8 miles = 37.18375, -113.67849 (4,556'). Snow Canyon Overlook (On Top of the World) = 37.20116, -113.66671 (4,765'). Maps/Apps: Topo Maps U.S. app, Garmin GPS, BLM Utah Red Mountain Wilderness (Avenza app). Maps at end of this post. Difficulty/Trail: strenuous Class 1-3 climb up Red Mountain (mild exposure) for the first 0.8 mile, moderate cross-country Class 2 over slick rock and deep sand. Date Hiked: 1/1/2024. Geology: Red Mountain's lower slopes are the Kayenta Formation, the oldest rock in Snow Canyon State Park (190 million years). The horizontal sediment layers are made from rivers depositing mudstone, siltstone and sandstone. The upper slopes, cliffs and top of Red Mountain are a great block of Navajo Sandstone that is younger (180 million years), also seen as a major rock unit of Zion National Park. This Navajo Sandstone exhibits large, sweeping cross-bed features - horizontal and dipping layers of ancient sand dunes deposited in a vast eolian (wind carried) dune field. Red Mountain is bounded by the Gunlock Fault on its west side. It merges with an extensive field of 2.4 million - 2,000 year old basalt flows to the northeast. The Gunlock Fault is a normal fault with the down-drop on its west side (See references below). Considerations: The first mile from the Ivins trailhead is Class 1-2 with two short Class 3 maneuvers. Once the trail tops out, there is no marked trail. Experience with navigation and route-finding using a compass/GPS and topo maps is advised after top of Red Mountain is reached to avoid getting lost. A sign at this trailhead reads, "Hazardous, unmaintained route with steep exposed slopes: your safety is your responsibility." Recommend taking a GPS waypoint at critical points on the trail such as point where you enter the plateau from the cliffs. Search and rescue operations for lost hikers have occurred. Be prepared if you have to spend the night! Research this route thoroughly! 2/5/23: Three rescues in Washington County on the same Day (St. George News). Related Posts Our New Year's Day Hike Fred and I have a tradition of hiking on New Years Day. For 2024, we took friends to the top of Red Mountain and across its beautiful plateau to a high point dubbed "On Top of the World" by our friend Dan. From here, you stand 1,400 feet over an outstanding view of Snow Canyon's petrified yellow sand dunes and orange ridges, black basalt flows from northern volcanoes near Veyo. It's worth the orange sand trudge on the top to get there. This short, five-mile hike packs in a good variety of terrain. The first mile climbs steeply through a cliff band requiring some fun Class 3 (un-roped using hands to climb) maneuvers, gaining 1,300 feet. The next 1.5 miles initially descends through a beautiful juniper woodland bowl where Gunsight Pass can be reached to the southeast. You will trek through sand, washes, over slick rock then climb to a sandy saddle where our "On Top of the World" high point can finally be seen. Then it's a matter of making a ~0.5-mile beeline to it across relatively level terrain, traversing minor washes, dodging cacti and prickly shrubs. When you top-off onto Red Mountain's plateau, you initially follow the north/south Red Mountain Primitive Trail for ~1.2 miles, then a short jaunt off of it to the northeast to reach On Top of the World, elevation 4,765'. Red Mountain Primitive Trail's northern trailhead is located just north of Diamond Cinder Cone on Utah Highway 18. It's a fun little scramble to the cairned top, using your hands a few times to climb easy rocks, overlooking Padre Canyon and Tuacahn Center for the Arts to the southeast. Once you summit, the rugged terrain drops steeply below with a breathtaking view of Snow Canyon, with a few smooth slick rock benches above it that look interesting to explore or camp in. Can't think of a better way to celebrate the New Year: friends and the reward of finding our own way to a seldom-visited summit in one of the most beautiful places in the southwest. Great "medicine" for the soul, body and mind. Explore More in 2024!! Southern Red Mountain trailhead in Ivins. The trail starts out steep! Google Earth view of our GPS tracks beginning at the Red Mountain Primitive Trail's southern trailhead in Ivins (lower left), going through the cliff-band about halfway up, getting onto Red Mountain, and traversing across plateau to "On Top of the World" overlooking Snow Canyon, Padre Canyon, and Tuacahn Center for the Arts. See more maps at the end of this post. Utah yucca and pinyon pines, shrub live oak (Quercus turbinella) on Red Mountain's plateau. The name turbinella, meaning "like a little top", refers to the acorn, this plant's fruit which appears in summer. The reference to "turbinella" in the photo above prompted me to add these photos of the shrub live oak acorns. They're so cute! Life and death on the Colorado Plateau: beauty and grace in a dead juniper. On top of Red Mountain: lots of sand and shrubs to negotiate. The first view of "On Top of the World" highpoint (red cone to the right). Snow-covered Pine Valley Mountains on the horizon. This photo was taken last winter when we had record snowfalls in southwestern Utah. We have just walked across the pinyon/juniper scrub land behind Fred and Jeff and are starting up the ridge to our summit. Beaver Dam Mountains on the horizon to the west. "On Top of the World!" A cairn marking our summit and a view of Tuacahn Center for the Arts lower left. View is looking south at Ivins and St. George, Utah and toward Arizona on the horizon. Jeff and Lindy - Happy New Years! Dan (who named this summit "On Top of the World") in a photo from last winter. The road in the valley is the drive through Snow Canyon State Park. Note the black shrub-covered basalt flows mid/upper in photo, covering the Navajo Sandstone. Heading back. As soon as you get over the saddle in the foreground, you drop into sand dunes and washes, then a brief climb up a sandstone ridge to find your entry point onto the plateau. Navigation experience on unmarked terrain is essential so you don't get lost. I recommend taking a GPS point when you finish the 0.8 mile climb from the trailhead to the plateau entry. Heading down off the plateau of Red Mountain on Red Mountain Trail. Overlooking the city of Ivins. City of Ivins below. Descending through Class 2+/3 cliff band. Below us is the trail on top of the ridge. Caltopo Map of our GPS tracks. Caltopo map illustrating our hikes on the Red Mountain Primitive Trail. Red tracks = "On Top of the World" hike. Blue tracks = our hike on 2/4/23. Dashed line = continuation of Red Mountain Primitive Trail past Snow Benchmark, to intersection with Snow Canyon Overlook, then ending at its upper trailhead. References

Bugden, M. Geology of Snow Canyon State Park Cryptobiotic Soils: Jayne Belnap. Holding the Place in Place - USGS: Impacts of Climate Change on Life and Ecosystems. Red Mountain Wilderness Maps - Wilderness Connect Ecoregions of Utah - usgs.gov Geologic Map of the St. George and East Part of the Clover Mountains 30' x 60' quadrangles, Washington and Iron Counties, Utah. Biek, R.F., and others. USGS publications. Miller, R. Our Geological Wonderland: Snow Canyon State Park A rare chance to walk in water in Badwater Basin, attempts to climb Artist Palette Peak and Sheephead Mountain, and a wrap-up of 2023 hikes. Sunset on Badwater Basin, Death Valley National Park, 12/23. photo by Fred Birnbaum Trip Stats

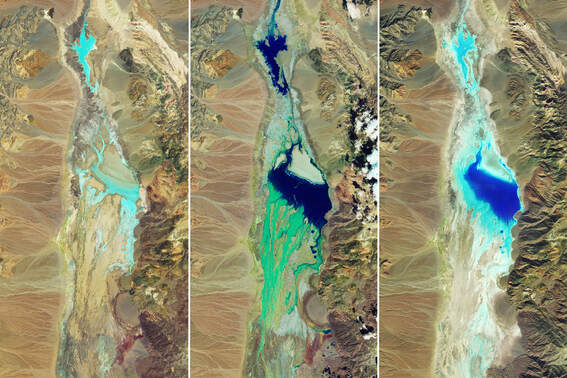

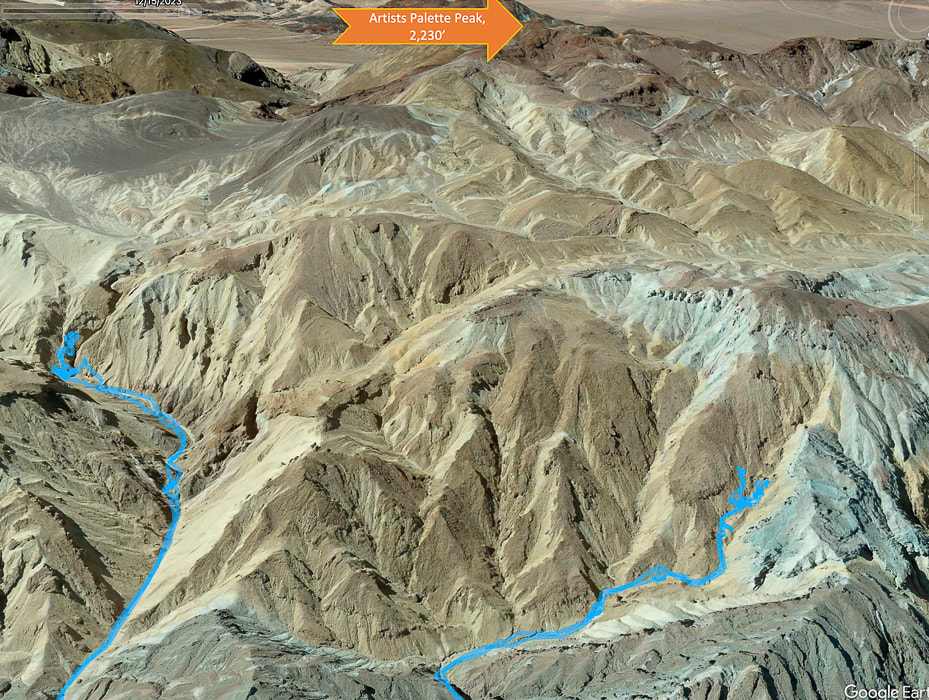

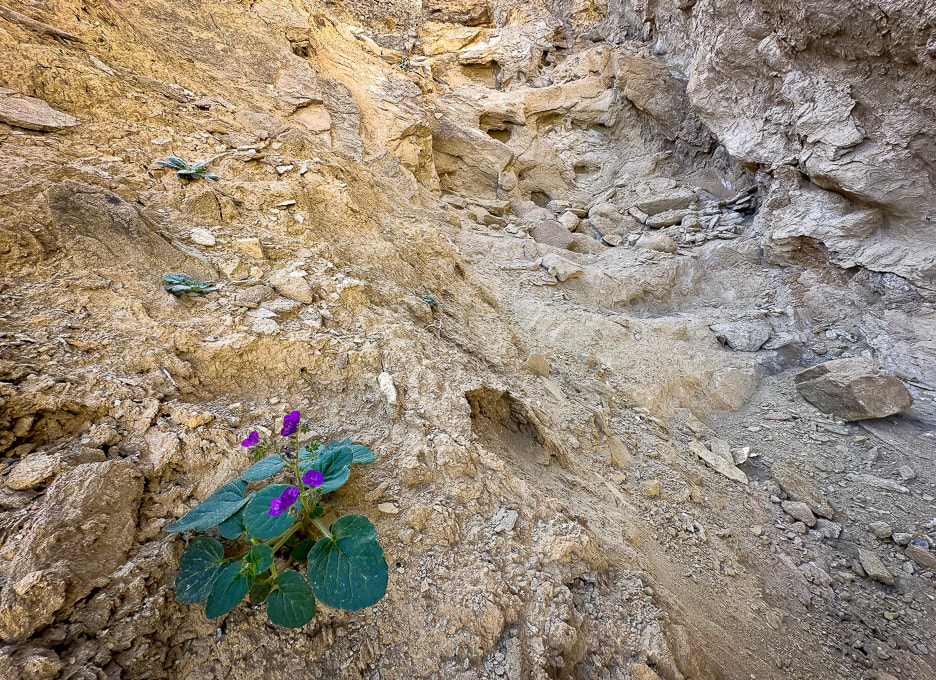

Peaks Attempted: Artist's Palette Peak, east Death Valley National Park, and Sheephead Mountain, Ibex Wilderness (southern Death Valley). Dates hiked: December 15 and 16, 2023. Maps and Apps: Trails Illustrated Death Valley National Park #221. Used Stavislost.com for Artist's Palette Peak and Sheephead Mountain routes. Lodging: Shoshone Inn at Shoshone Village, southwest of Death Valley NP. Geology: Tectonic processes relatively young; rocks are old Precambrian - 1.8 billion years ago. Schists and gneisses that have been uplifted and exposed, located in the Panamint Mountains to the west of Death Valley and Badwater Basin. Paleozoic - 550 million years ago. Limestone and dolomite in warm shallow seas. Late Paleozoic/Mesozoic - 225-65 million years ago. Pacific plate subducted under North American plate, causing melting ---> magma and volcanism. Jurassic and Cretaceous - magma chamber production ---> cooled intrusions that formed the Sierra Nevada mountains ---> some of these plutons spread eastward to Death Valley. Compression caused thrust faults (older rock thrust over younger rock). Cenozoic - 66 million years ago - present. Extension (spreading) caused volcanism Related Posts One of the photographers at Badwater Basin's lake. Our Trip - Badwater Basin, Artist's Palette Peak, Sheephead Mountain On August 20, 2023, Tropical Storm Hilary dumped a year's worth of rainfall on Death Valley National Park, transforming famous Badwater Basin into a spectacular sight: a huge turquoise-colored, salt-rimmed lake reflecting massive mountains on both sides. This rare occurrence is reminiscent of Pleistocene Lake Manly, a deep ice-age body of water that once filled this basin and dried up about 10,000 years ago. Although not as deep and extensive as its predecessor, it was still an amazing sight to see, especially at sunset. Badwater Basin, the lowest point in North America, is normally a salt flat cut into hexagons, and freeze/thaw hummocks - soft yet crunchy to walk on. Fred and I had hurried from Shoshone Village, a 45-minute drive to the southeast, to get there by sunset. There were a few other photographers, their mirror-images appearing unbroken in the still, shallow, and salty water. It was so quiet and remote that we could hear their conversations. For the past three years, we have stayed and hiked in the Death Valley National Park area during the Christmas holiday. In 2021, we hiked Pahrump Point out of Chicago Valley in the Nopah mountains with our friend Scott. In 2022, Fred and I hiked the awesome Pyramid Peak in the Funeral Mountains, and in 2023 we got to experience the magic of Badwater Basin's reflections and also hike Artists Palette Peak and Sheephead Mountain in the Ibex Wilderness. Hikes are challenging in Death Valley, a rough and rocky place - remote, stoic and mysterious. That's why we love it. A land that has experienced a lot of turmoil, yet stands defiant. How Long will Badwater Basin's Lake Last? The depth of the lake was about four inches where I stood after walking through thick (and sharp!) salt deposits at the lake margins. The evaporation rate in Death Valley is 120-150 inches per year. I read one source that stated the depth was two feet right after the storm. The evaporation rate is the highest in the U.S., so get out and see it soon! The Landsat images below show relative evaporation in 10.5 weeks (images 2 and 3). Note that the northern, smaller body of water appears to have mostly dried up already. National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Landsat Images of Badwater Basin in Death Valley National Park. Water appears in shades of blue. Image #1 taken 7/5/23 shows little moisture. Image #2 taken 8/22/23, two days after Tropical Storm Hilary's record rainfall. Image #3 taken on 11/2/23, 10.5 weeks after the flooding, shows some evaporation. NASA Earth Observatory images by Wanmei Liang, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey. Sodium chloride (table salt) crystals accumulated around the perimeter of this year's lake that filled in part of Badwater Basin, a rare event. This lake has the greatest evaporation rate in the U.S. Fred at the salty Badwater Basin, the lowest point in North America - a sublime setting. Artist's Palette Peak and Sheephead Mountain Our experience with gnarly-looking loose, slippery scree slopes (Idaho's Leatherman Peak is one) and Class 3 boulder obstacles made us turn back once we got closer to these summits. Both of these hikes involve Class 2 and 3+ route-finding, as there are no trails or markers. I frequently go to stavislost website to plan summits, and study topo maps to understand the terrain. Maybe we are, in our 60's, getting too old for these treacherous scrambles - or we just don't want to put ourselves through the frustration! Seems like we've had more "grudge peaks" than usual this year. Tough Terrain to Artists Palette Peak, top of image (looking south). Another Grudge Peak! Our GPS tracks in blue. Twenty Team Mule Canyon to the left, we ran into Class 3+. Steep and loose talus slope out of canyon to the right. We began ascending Artist's Palette Peak via Twenty Mule Team Canyon heading mostly south, after parking on 20 Mule Team Road, accessed from Highway 190. Evidence of a recent heavy wash-out with a freshly-carved stream (maybe from Tropical Storm Hilary?) coursed through the canyon floor. Huge boulders had been dropped into the canyon. We scaled a small waterfall and had no difficulty until we reached a Class 3+ boulder obstacle, blocking our progress. Shortly before this, we were able to hoist ourselves over a huge tilted boulder by standing on unstable rocks piled up against it to make a platform (glad I had Fred to help me place my feet in the right spot on these tippy rocks on the way down!). Hoping we were golden but discovering we were not after the next canyon turn, we tried a few ways to get past the next boulder array but decided to descend and try a different canyon. It would have meant climbing a very steep and loose slope of gravel, where I was slipping more than I was ascending. The canyon floor had signs of a recent wash-out. Twenty Mule Team Canyon Toward the top of Twenty Mule Team Canyon - we were able to ascend this narrow, wobbly stack of rocks to hoist over this boulder but then met up with Class 3+ moves after this that proved too intimidating. The obstacle in the above photo is where another Artist's Palette Peak hiker who recorded his trip on Peakbagger website turned around. Stav Basis, in his route description of this hike advises that if you are hiking Twenty Mule Team Canyon to ascend it rather than descend it to make sure you can maneuver the Class 3+ stuff and you don't get stuck. The next canyon we attempted to the northwest of Twenty Mule Team Canyon had footprints in it, possibly from a group of hikers we saw at the trailhead. We followed it, fun scrambling over easy walls, until we were diverted out of the canyon to see a steep and loose talus slope with no end in sight. It's frustrating to know that "obstacles" like this get in your way of seeing your intended peaks and knowing there was less-steep terrain above. But that's why off-trail route finding in Death Valley is so rewarding - you have really earned the view from the summit and the access to the peak register. There is no other place like Death Valley's terrain - mostly devoid of vegetation. Rocks and sky predominate, but sometimes you get a remarkable surprise, like the blood red and magenta Desert five-spot flower growing in the gravel (photo below). Conglomerate boulder containing mostly rounded cobbles from long-ago streams. Desert five-spot Eremalche rotundifolia Route up canyon on the right - fun scrambling. Looking down a "rock ladder" we climbed from the canyon floor. Shortly after this we came to the steep and long loose talus slope and decided to turn back. Sheephead Mountain (13 ascents on Peakbagger - A Sierra Club Desert Peaks Section Peak) I had been looking forward to hiking in the Ibex Wilderness, so the next day when we hiked to Sheephead Mountain, we were remote and alone, except for the occasional motorist on Highway 178, which begins at Shoshone, then heads west through two passes to turn north as it becomes Badwater Road, hugging the east side of Death Valley. We parked in a pull-out at Salsberry Pass, about 12 miles from Shoshone. The faint trail that headed southeast toward Sheephead soon became non-existent, so the approach was a maze of red washes and rubbly hills. We located our daunting-looking mountain to the south. We ascended a rotten, slippery and steep ridge of yellow scree too soon. Once we got on top of this yellow high point, we realized it would have been easier to ascend the red ridge just to the south, leading more directly to the saddle on the final ridge to Sheephead, which looked like a tower with more loose scree slopes flanking its sides. We didn't have the motivation in us to attempt the rock piles. From the saddle we found an easier way down over a ridge and then dropping into a wash. We instead walked back to the highway, crossing it and wandering on a ridge toward Salsberry Peak, seeing occasional bighorn sheep signs. Wrap-Up of 2023 hiking - The Year of Grudge Peaks This year we did more remote desert route-planning and finding on unmarked terrain with no trails in Utah's Zion Wilderness and San Rafael Swell, Nevada and Death Valley. Occasionally we see cairns that let us know some other hardy souls had stood in the same place. Walking without a trail takes more time. As a result, we had more "grudge peaks" this year - ones where we did not make the summit. Mummy Mountain was the most frustrating; we were within 200 feet of the summit and ran into a deep and steep snow-filled gully with no great footing to get out of it to a narrow shelf to the top. Scott, Fred and I will hopefully try this summit again but from the more-used trail on other side of the mountain. Other "grudges" this year were Hepworth in Zion, and Bearing Peak in Lake Mead National Park. Moapa's knife's edge we're not sure we would attempt again. Successful summits included Shelly Baldy in the Tushars, Mt. Kimball in Tucson, Jackson Peak near Boise, and Burger Peak in Pine Valley Mountains. And, the summit of Angels Landing was sweet because we got to hike it with my sis and bro-in-law. One of my favorite authors, Willa Cather famously said, "The road is all, the end is nothing." As far as reaching summits, I would have to respectfully disagree. The way to the summit is a great experience, but to stand on the summit after you've worked hard to climb it is even sweeter. So, is it our age or the pursuit of more technically challenging hikes that are preventing us from reaching our goals? I like to think it's a little of the first and mostly the last of those two reasons. Should we focus less on goals and more on appreciating just "being out there?" - not to always define "success" as achieving a summit? Of course, I love being out there in our American West, but my goal-driven trait wants more. At any rate, it's been fun to try something different and work on navigation skills in more remote country. I count myself as one of the lucky ones who gets to even consider this conundrum in the first place. Keep On Exploring! Walking southeast toward Sheephead Mountain (with notch on horizon 1/3 in from left). Sheephead Mountain on horizon to the right. The loose and steep yellow scree slope we ascended, but didn't descend. Reaching the top of the yellow scree slope and the ridge leading to Sheephead Mountain. Ridge leading to Sheephead Mountain. We descended down the red slope to the right. Fred at top of yellow ridge. Sheephead on horizon! Looking southwest toward Talc Hills and Black Mountains. On our descent over red rocks - looking at our ascent over the not-so-fun loose yellow rock. Looking toward the northwest. Parting shot - the ascent (Sheephead on the right) looks manageable from here! Bright cobblestone lichen? A few more images near Zabriskie Point in northeast Death Valley National Park... References

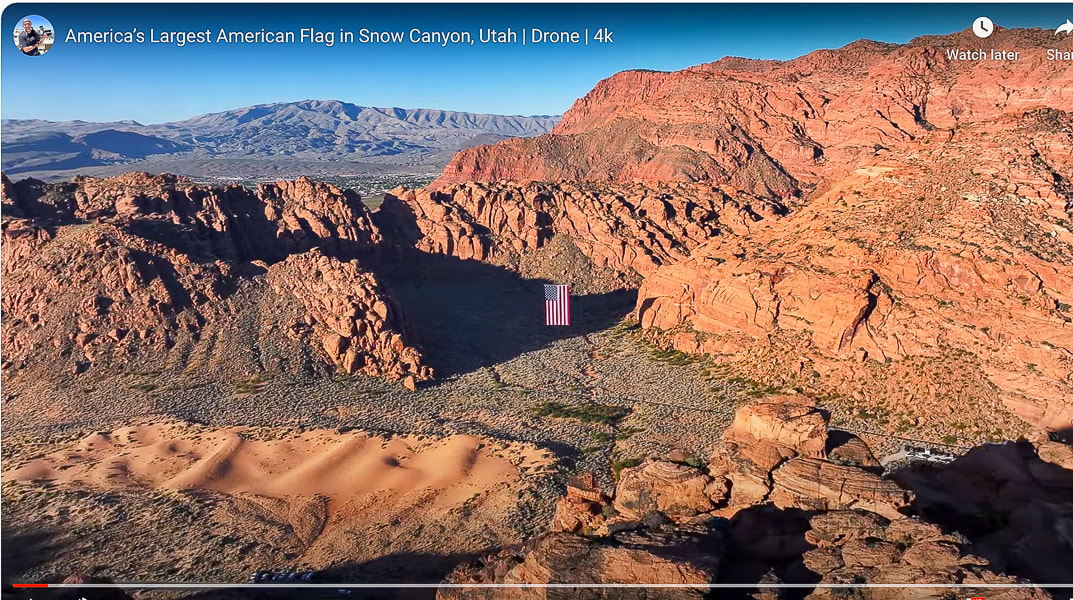

Fish, N. From Indiana University. https://sierra.sitehost.iu.edu/papers/2008/fish.html Doermann, L. NASA Earth Observatory. Floodwaters Fill Badwater Basin. Hunt, C.B., et al. 1966. Hydrologic Basin Death Valley California. Geological Survey Professional Paper 494-B. A stunning sight on Veteran's Day: the largest American flag juxtaposed with the soaring cliffs of Snow Canyon State Park. Lady Liberty, displayed by Follow the Flag organization, at night in Snow Canyon State Park, Utah. Photo by Ann Little Related pages in Explorumentary: Follow the Flag Organization Facts

Check out awesome drone footage in these great videos! Saville Creations: America's Largest American Flag in Snow Canyon St George News Founders: Kyle and Carrie Fox

Motivation: To strengthen Americans' patriotism, a simple idea of inspiring, strengthening and healing people by hanging one of their huge flags in a canyon produced "far more impact than ever anticipated." Other events:

Mission Statement

American Flag Etiquette

Click on video below for awe-inspiring drone video

An unexpected sight greeted Fred and I on our favorite local loop-hike last month in Snow Canyon State Park. Just off Whiptail trail, suspended high in a gap between orange cliffs, hung an enormous American flag, seemingly out of place in in these walls of Navajo Sandstone. People were lined up, taking pictures of this spectacular sight. The flag, in the still air hung vertically, but billowed and rolled with occasional breezes, the bottom edge of it flying gracefully towards the sky. It was suspended in mid-air, with its hanging wires barely visible. I suppose you could ask what visitors were thinking about this huge flag in this gorgeous natural setting and you would probably get different answers, ranging from the emotion of national pride and patriotism to "Wow! That's pretty cool!" to "Why is it hanging here?" For me, my heart swelled because two things that I love were juxtaposed: a symbol of my country and the land of the American West.

Strength, unity, connection, freedom - these are what the American flag is intended to signify. The stripes represent the original 13 colonies that were seceding from the British. The blue canton contains the stars of our 50 states. Blue represents vigilance, perseverance, and justice. White signifies purity and innocence, and red signifies hardiness and valor. This proved to be a good exercise in brushing up on my flag facts, reading America's unique Declaration of Independence, and learning of the efforts going on to unify our country. Pew and Gallup polls show that a record high number of Americans perceive the nation as divided on the most important issues. Maybe Follow the Flag and other organizations can help us see the positive and help us remember the ideals of our country's origin. "...if there’s one impression I carry with me after the privilege of holding for five and a half years the office held by Adams and Jefferson and Lincoln, it is this: that the things that unite us — America’s past of which we’re so proud, our hopes and aspirations for the future of the world and this much-loved country — these things far outweigh what little divides us. And so tonight we reaffirm that Jew and gentile, we are one nation under God; that black and white, we are one nation indivisible; that Republican and Democrat, we are all Americans. Tonight, with heart and hand, through whatever trial and travail, we pledge ourselves to each other and to the cause of human freedom, the cause that has given light to this land and hope to the world." - President Ronald Reagan's Independence Day Speech aboard the USS John F. Kennedy, July 4, 1986. |

Categories

All

About this blogExploration documentaries – "explorumentaries" list trip stats and highlights of each hike or bike ride, often with some interesting history or geology. Years ago, I wrote these for friends and family to let them know what my husband, Fred and I were up to on weekends, and also to showcase the incredible land of the west.

To Subscribe to Explorumentary adventure blog and receive new posts by email:Happy Summer!

About the Author

|